When Lineo Tsikoane gave birth to her daughter, she was inspired to intensify her advocacy for gender equality to give Nairasha a better life as a girl growing up in Lesotho.

“I think a big light went off in my head to say, “What if the world that I’m going to leave will not be as pure as I imagine?” I ask myself, “What kind of world do I want to leave my daughter in?”” she says.

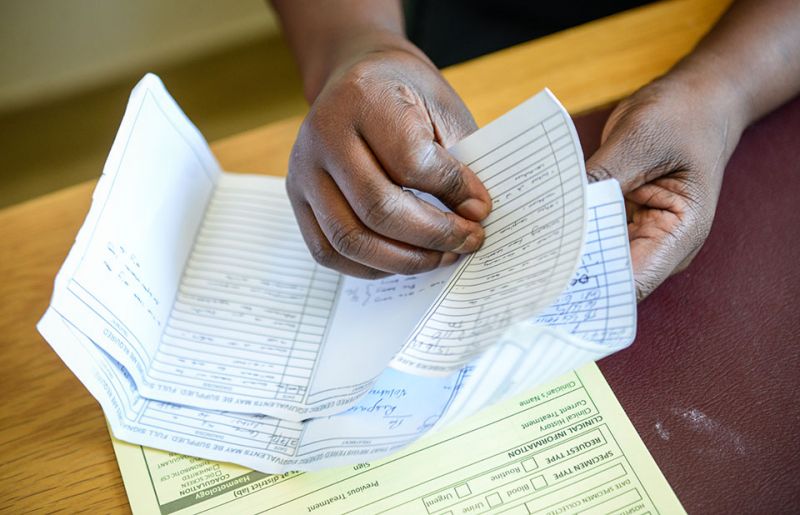

As a result, Ms Tsikoane champions for women’s social, economic and legal empowerment at her firm, Nairasha Legal Support. It offers legal support for women in small and medium enterprises and women who are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

“Our main focus is gender-based violence, because this happens to be a country that has one of the highest incidences of rape and intimate partner crime in the world,” she says.

Even before the COVID-19 outbreak, violence against women and girls had reached epidemic proportions globally.

According to UN Women, 243 million women and girls worldwide were abused by an intimate partner in the past year. In Lesotho, it is one in three women and girls.

Less than 40% of women who experience violence report it or seek help.

As countries implemented lockdown measures to stop the spread of the coronavirus, violence against women, especially domestic violence, intensified—in some countries, calls to helplines increased fivefold.

In others, formal reports of domestic violence have decreased as survivors find it harder to seek help and access support through the regular channels. School closures and economic strains left women and girls poorer, out of school and out of jobs, and more vulnerable to exploitation, abuse, forced marriage and harassment.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) works together with UNAIDS, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization on 2gether4SRHR, a joint programme funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, to address HIV and sexual and reproductive health in Lesotho.

During Lesotho’s lockdowns, UNFPA worked with Gender Links, the Lesotho Mobile Police Service and others to support efforts to prevent and respond to incidences of gender-based violence.

“We are ensuring that a helpline, where people experiencing gender-based violence can call, is in place and is working and we are also providing relevant information through various platforms for people to access all the information they need on gender-based violence,” says Manthabeleng Mabetha, the UNFPA Country Director for Lesotho.

Mantau Kolisang, a local policeman from Quthing, Lesotho’s southernmost district, characterized by rolling hills and vast landscapes, says one reason why gender-based violence is prevalent in Lesotho is because the law is not heeded in the rural areas.

“It’s difficult to implement the law since these are remote areas,” he says, adding that while he has made arrests, he has no transport to access far-flung areas in the small mountainous region.

Lesotho’s law states that a girl can marry at the age of 16 years. However, Mr Kolisang says cultural practices, coupled with contraventions of the law, has made some men believe a 13-year-old girl “can be a wife”, exposing Basotho girls to violence.

“Men don’t regard it as a crime,” he says, adding that girls have been abducted from the mountains for forced marriages.

Between 2013 and 2019, 35% of adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa were married before the age of 18 years. Girls married before 18 years of age are more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those married after the age of 18.

Because of poverty, gender inequality, harmful practices (such as child, early or forced marriage), poor infrastructure and gender-based violence, girls are denied access to education, one of the strongest predictors of good health and well-being in women and their children.

In Lesotho’s legal system, women are regarded as perpetual minors. This categorization infantilizes women, Ms Tsikoane says. A man who abuses a woman can often walk away unscathed from the justice system if he says the woman in question is his “wife”, she adds.

“This makes women vulnerable to commodification because a child can be passed around,” she says.

Ms Tsikoane says there is a direct link between the minority status of women and HIV infection in Lesotho. In 2019, there were 190 000 women 15 years and older living with HIV in Lesotho, compared to 130 000 men.

Adolescent girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 24 years are particularly vulnerable. They accounted for a quarter of the 11 000 new HIV infections in Lesotho in 2019.

“My hypothesis is women cannot negotiate safe sex,” says Ms Tsikoane.

The dangerous reality that Basotho women live in worries Mr Kolisang. But due to a lack of institutional support and resources, he feels his actions have limited effect.

“I feel for these children. I feel for these women. I do feel for them. I can help, but the problem is how?” he laments.

Ms Tsikoane says she finds “trinkets of opportunities” for her and her colleagues to help their clients and navigate a legal system that is not favourable towards women.

“So, if you are not being well assisted at a police station, if you feel like someone is dragging your case and you are struggling to get an audience, we are there. We will support you and we will fight with you,” she says.