With male circumcision and its links to HIV acquisition hitting the headlines and sparking debates around the world, in the first of a special three-part series on the issue, www.unaids.org takes a closer look at the historical, traditional and increasingly social reasons behind the practice of male circumcision across the world.

Male circumcision is one of the oldest and most common surgical procedures known, traditionally undertaken as a mark of cultural identity or religious importance.

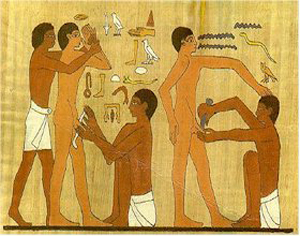

Historically, male circumcision was practised among ancient Semitic people including Egyptians and those of Jewish faith, with the earliest records depicting circumcision on Egyptian temple and wall paintings dating from around 2300 BC.

With advances in surgery in the 19th century, and increased mobility in the 20th century, the procedure was introduced into some previously non-circumcising cultures for both health-related and social reasons.

According to current estimations, approximately 30% of all males across the world— representing a total of approximately 670 million men — are circumcised. Of this number, about 68% are of Islamic faith, less than 1% of Jewish faith, and 13% are non-Muslim, non-Jewish Americans.

“With the recent findings that male circumcision significantly reduces a man’s risk of acquiring HIV the practice is receiving renewed interest as the world looks to understand what this will mean for HIV prevention,” said UNAIDS Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Catherine Hankins. “Looking at the determinants of male circumcision, and the acceptability of male circumcision in non-circumcising societies give a better picture of how to take the latest research findings forward.”

Religious practice

In the Jewish religion, male infants are traditionally circumcised on their eighth day of life, providing there is no medical contraindication. The justification, in the Jewish holy book the Torah, is that a covenant was made between Abraham and God, the outward sign of which is circumcision for all Jewish males. The Torah states: “ This is my covenant, which ye shall keep, between me and you and thy seed after thee: every male among you shall be circumcised " (Genesis 17:10). Male circumcision continues to be almost universally practiced among Jewish people.

Islam is the largest religious group to practice male circumcision. As an Abrahamic faith, Islamic people practice circumcision as a confirmation of their relationship with God, and the practice is also known as ‘tahera’, meaning purification. With the global spread of Islam from the 7th century AD, male circumcision was widely adopted among previously non-circumcising peoples. There is no clearly prescribed age for circumcision in Islam, although the prophet Muhammad recommended it be carried out at an early age and reportedly circumcised his sons on the seventh day after birth. Many Muslims perform the rite on this day, although a Muslim may be circumcised at any age between birth and puberty.

The Coptic Christians in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians— two of the oldest surviving forms of Christianity— retain many of the features of early Christianity, including male circumcision. Circumcision is not prescribed in other forms of Christianity. In the New Testament, St. Paul wrote: "in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision count for anything" (Galatians 5:6) and a Papal Bull issued in 1442 by the Roman Catholic Church stated that male circumcision was unnecessary: “Therefore it strictly orders all who glory in the name of Christian, not to practise circumcision either before or after baptism, since whether or not they place their hope in it, it cannot possibly be observed without loss of eternal salvation,” it stated. Focus group discussions on male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa found no clear consensus on compatibility of male circumcision with Christian beliefs. Some Christian churches in South Africa oppose the practice, viewing it as a pagan ritual, while others, including the Nomiya church in Kenya, require circumcision for membership and participants in focus group discussions in Zambia and Malawi mentioned similar beliefs that Christians should practice circumcision since Jesus was circumcised and the Bible teaches the practice.

Ethnicity

Circumcision has been practiced for non-religious reasons for many thousands of years in sub-Saharan Africa, and in many ethnic groups around the world, including aboriginal Australasians, the Aztecs and Mayans in the Americas, inhabitants of the Philippines and Eastern Indonesia and of various Pacific Islands, including Fiji and the Polynesian islands.

In the majority of these cultures, circumcision is an integral part of a rite-of-passage to manhood, although originally it may have been a test of bravery and endurance. “Circumcision is also associated with factors such as masculinity, social cohesion with boys of the same age who become circumcised at the same time, self-identity and spirituality,” Dr Hankins explained.

The ethnographer Arnold Van Gennep in his 1909 work ‘The Rites of Passage’ , describes various initiation rites which are present in many circumcision rituals. These include a three stage process: separation from normal society; a period during which the neophyte undergoes transformation; and finally reintegration into society in a new social role.

“A psychological explanation for this process is that ambiguity in social roles creates tension, and a symbolic reclassification is necessary as individuals approach the transition from being defined as a child to being defined as an adult. This is supported by the fact that many rituals attach specific meaning to circumcision which justify its purpose within this context,” said Dr Hankins. For example, certain ethnic groups including the Dogon and Dowayo of West Africa, and the Xhosa of South Africa view the foreskin as the feminine element of the penis, the removal of which (along with passing certain tests) makes a man of the child.

Tradition plays a major part for many ethnic groups. Among ethnic groups of Bendel State in southern Nigeria, 43% of men stated that their motivation for circumcision was to maintain their tradition. In some settings where circumcision is the norm, there is discrimination against non-circumcised men. For the Lunda and Luvale tribes in Zambia, or the Bagisu in Uganda, it is unacceptable to remain uncircumcised, to the extent that forced circumcisions of older boys are not uncommon. Among the Xhosa in South Africa, men who have not been circumcised can suffer extreme forms of punishment, including bullying and beatings.

Circumcision as a social statement

Social reasons behind male circumcision are becoming ever more common. “The desire to conform is an important motivation for circumcision in places where the majority of boys are circumcised,” said Dr Hankins.

A survey in Denver, US where circumcision occurs shortly after birth, found that parents, especially fathers, of newborn boys cited social reasons as the main determinant for choosing circumcision (e.g. not wanting the son to ‘look different’ from the father).

In the Philippines, where circumcision is almost universal and typically occurs at age 10-14, a survey of boys found two-thirds of those surveyed choosing to be circumcised simply ‘to avoid being uncircumcised’, and 41% stating that it was ‘part of the tradition’. Social concerns were also the primary reason for circumcision in South Korea with 61% of respondents in one study believing they would be ridiculed by their peer group unless they were circumcised.

The desire to ‘belong’ is also likely to be the main factor behind the high rate of adult male circumcisions among immigrants to Israel from non-circumcising countries (predominantly the former Soviet Union).

In a number of countries, socio-economic factors also influence circumcision prevalence, especially in countries with more recent uptake of the practice such as English-speaking industrialised countries. When male circumcision was first practised in the United Kingdom in the late 19th and early 20th century, it was most prevalent among the upper classes. In the US, a review of 4.7 million newborn male circumcisions nationwide between 1988 and 2000 also found a significant association with private insurance and higher socioeconomic status.

Perceived health and sexual benefits

In more recent times, perceptions of improved hygiene and lower risk of infections through male circumcision have driven the spread of circumcision practices in the industrialised world.

In a study of US newborns in 1983, mothers cited hygiene as the most important determinant of choosing to circumcise their sons, and in Ghana, male circumcision is seen as cleansing the boy after birth. Improved hygiene was also cited by 23% of 110 boys circumcised in the Philippines and in South Korea, the principal reasons given for circumcision were ‘to improve penile hygiene’ (71% and 78% respectively) and to prevent conditions such as penile cancer, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. In Nyanza Province, Kenya, 96% of uncircumcised men and 97% of women irrespective of their preference for male circumcision stated their opinion that it was easier for circumcised men to maintain cleanliness.

Perceived improvement of sexual attraction and performance can also motivate circumcision. In a survey of boys in the Philippines, 11% stated that a determinant of becoming circumcised was that women like to have sexual intercourse with a circumcised man, and 18% of men in the study in South Korea stated that circumcision could enhance sexual pleasure. In Nyanza Province, Kenya, 55% of uncircumcised men believed that women enjoyed sex more with circumcised men. Similarly, the majority of women believe that women enjoyed sex more with circumcised men, even though it is likely that most women in Nyanza have never experienced sexual relations with a circumcised man. In northwest Tanzania, younger men associated circumcision with enhanced sexual pleasure for both men and women, and in Westonaria district, South Africa, about half of men said that women preferred circumcised partners.

Expected increase in demand

Global estimates in 2006 suggest that about 30% of males — representing a total of approximately 670 million men — are circumcised.

With latest research findings suggesting that circumcised men have a significantly lower risk of becoming infected with HIV, demand for safe, affordable, male circumcision is expected to increase rapidly.

“Since male circumcision is now shown to be effective in reducing the risk of HIV acquisition, care must be taken to ensure that men and women understand that the procedure does not provide complete protection against HIV infection,” said Dr Hankins, underlining that these issues will be discussed at the “ Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention Research - Policy and Programme Implications” International Consultation to be held in Montreux from 6-8 March 2007. “Male circumcision must be considered as just one element of a comprehensive HIV prevention package that includes the correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reductions in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations and abstaining from penetrative sex. Just as combination treatment is the best strategy to treat HIV, combination prevention is the best strategy to avoid acquiring or transmitting HIV”, she added.

“Action is also required to improve the safety of circumcision practices in many countries and to ensure that health care providers and the public have up-to-date information on the health risks and benefits of male circumcision,” she said.

Links:

Read Part 2 - Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now

Read Part 3 - Moving forward: UN policy and action on male circumcision