Feature Story

Transforming lives through voluntary drug treatment

16 March 2017

16 March 2017 16 March 2017Hendro was a driver for a private company in Jakarta, Indonesia, when a colleague introduced him to heroin two years ago.

“I started to get addicted,” said Hendro, who prefers to use his first name only. “Soon, my body didn’t feel good if I wasn’t consuming drugs. I couldn’t concentrate. This lasted for about seven months before my life descended into chaos.”

His work suffered and he got into daily arguments with his wife. He would whisper to himself, “This is not right. I will destroy myself. Every day, I kept trying to stay away from drugs, but the craving for the drug was so painful. It was unimaginable.”

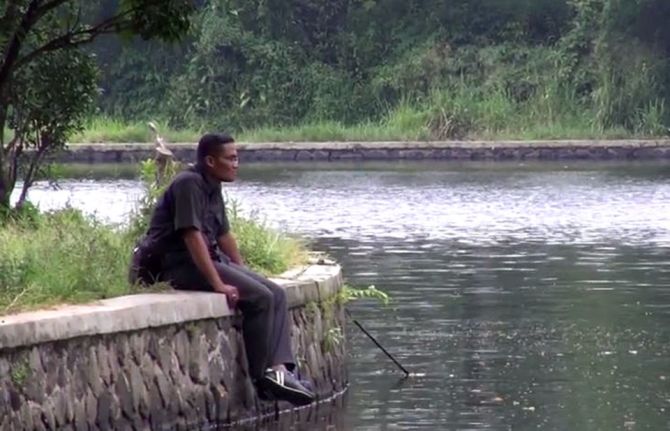

One day Hendro heard about an innovative drug programme based in a large house in Bogor, an hour outside of Jakarta. The cheerful building with a freshly cut lawn exudes a warm and friendly atmosphere, which is accentuated by two dogs who greet visitors with a couple of friendly sniffs.

Sam Nugraha founded Rumah Singgah PEKA in 2010. “PEKA is different from other treatment centres, because it is fully voluntary,” he said. “Every client has made their own decision to participate.”

There are 4 million people who inject drugs in the Asia and the Pacific region—that’s one third of the people who inject drugs globally. This places the region at the forefront of the largest injecting drug problem in the world.

A common response to drug use in the region is the confinement of people who inject drugs in compulsory treatment and rehabilitation centres.

“PEKA’s approach cannot be applied to everyone. Clients have to be conscious of what they need to do and ready to make changes,” said Mr Nugraha.

Before participants enrol in PEKA, they undergo a lengthy assessment to determine if the facility fits their needs.

“When I came to PEKA I was determined to recover and to rediscover the person who was lost because of drugs,” recalled Hendro.

Clients discuss with their counsellors the best treatment plan. They can choose to live in or outside of PEKA, but if they opt for the boarding option, they must respect the facility’s zero tolerance for the consumption of drugs while on its premises. Some clients select complete abstinence, others enrol in opioid substitution therapy and for those who wish to continue to inject drugs, PEKA has a needle and syringe programme. All clients are encouraged to have group and individual therapy sessions.

“Ninety per cent of our staff have experience with using drugs,” said Mr Nugraha, “so they understand the challenges clients are facing, as well as the type of support they need.”

Hendro decided to board and to participate in the methadone maintenance treatment programme. A counsellor accompanied him to a public clinic, where the doctor determined his optimal dose of methadone. He started off with 50 mg every day, but after a year has been bringing the dose down.

PEKA works in partnership with public clinics. Staff not only accompany clients to access methadone, but pick up a five-day supply of methadone for individuals who have established a steady routine and bring it back to the facility.

“Public health clinics have limited working hours and so we fill the gap by providing 24-hour services,” said Mr Nugraha. “People can come here at any time.”

Agustina Susana Iswati, Head of the Gedung Badak Health Clinic, agreed. “The cooperation with community groups is very much needed as they know what is really happening.”

People who inject drugs are vulnerable to HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs is higher than 30% in several Asian cities. Only 30% of people who inject drugs in Asia and the Pacific know their HIV status.

“We offer all our clients access to HIV testing. If the test result is positive, we help them start antiretroviral therapy as soon as possible,” said Mr Nugraha.

Evi Afifah, who is with the Mahdi Bogor Hospital, finds the collaboration with PEKA on HIV services helpful. “PEKA helps us reach our friends who are most in need of HIV testing, treatment and care,” she said.

Since 2010, PEKA has provided a range of services to almost 1000 clients. Follow-up surveys conducted with people who went through the full treatment programme indicate promising results. A significant number of clients reported that their drug dependency and quality of life had improved and their involvement in criminal activities had sharply declined.

This success has won local recognition. The organization was recognized by the Mayor of Bogor as an excellent institution in 2014 and 2016.

“PEKA is an organization that has gone through the test of time,” said Bima Arya Sugiarto, Mayor of Bogor. “With its vast experience, PEKA deserves our recognition, which can also motivate other community groups to be consistent and focused in their work.”

Perhaps the most important endorsement for PEKA is its clients, some of whom now work for the organization.

Iko, who is an HIV peer counsellor, said, “Aside from helping other people who use drugs, I am actually helping myself. That’s the main point. It makes me happy.”

After nine months of living at PEKA, Hendro was able to return home to his family and start working again as a driver. His experience was life-changing.

“At PEKA, I felt embraced as part of a family again. When I was using drugs, I was estranged and abandoned. Here, I found strength again,” said Hendro.

UNAIDS is working to support countries to reach the targets set out in the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS, which include ensuring access to combination HIV prevention options, including harm reduction, for 90% of people who inject drugs.