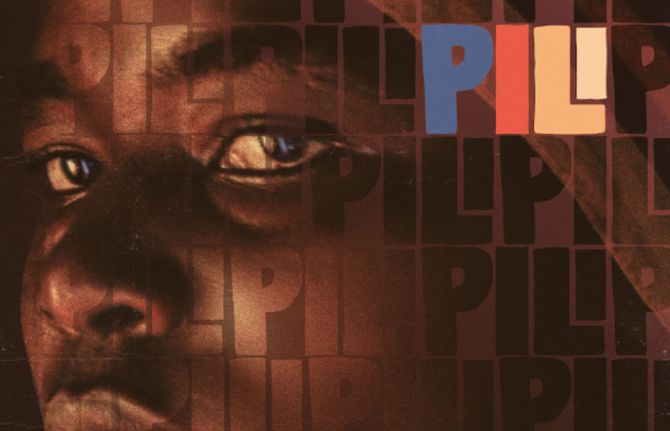

Feature Story

Pili movie focuses on the universal aim for a better life

28 February 2018

28 February 2018 28 February 2018Carrying a hoe over her shoulder as she ambles along a dirt road, Pili, a young Tanzanian woman, eyes an empty market stall. Talking to her friend while clearing a field, she says, “Digging all day, fighting for money, I can't do this my whole life.”

So begins the movie Pili, which focuses on a single mother with two children trying to make a better life for herself and her family. Farm work pays less than US$ 2 a day and the 25-year-old has a hard time keeping up with childcare, school supplies and medical check-ups. Pili lives with HIV and struggles to keep her HIV status a secret. She fears stigma and is scared that she will not get a loan to pay for the market stall she dreams of renting.

Produced by Sophie Harman and directed by Leanne Welham, the movie draws you into Pili’s daily struggles to gather money to become her own boss. Spoiler alert: she succeeds, but at a cost.

Ms Harman, an academic at the Queen Mary University of London, never dreamed of making a film. But she realized that a movie could be a collaborative project that would enable her to highlight the plight of many women.

“When I teach, I often have used film, which is very impactful, so I wanted to do my own film, but as a realistic feature based in Africa,” Ms Harman said.

In 2015, she won an AXA Insurance Outlook Award in recognition for her work in global health politics and HIV governance. The award gave her the money, but she needed a movie director—film-makers were wary about producing a film with untrained actors on a shoestring budget in the middle of nowhere. Within a year, though, she met Leanne Welham, a short-film director with years of experience in Africa.

What clinched the deal was Ms Harman’s access to the communities among which the film was to be made. Having started a nongovernmental organization in 2006 called Trans Tanz, Ms Harman had been inspired by women’s stories. Trans Tanz provides free transport for people living with HIV in rural areas so they can go to clinics.

Ms Welham and Ms Harman pitched their movie idea to the community and started compiling stories based on real-life experiences.

“To protect the women, we stressed to everyone that this would be a story based on our 80 interviews and my research,” Ms Harman explained. The community approved and gave feedback on the screenplay.

They now needed characters and to cast the leading actress, Pili. During an audition, Ms Welham met Bello Rashid, who had come to the session out of curiosity with her older sister. The young woman overcame her shyness and responded well to direction and landed the role.

Because of the language of the movie (Swahili), and the varying degrees of literacy, the British film crew mixed improvisation with a script. The film was set in Miono, a village near the Tanzanian coast.

“The cast are all real people, with only one trained actor, and 65% of them are living with HIV,” explained Ms Harman. “I wanted to protect the women and make this as anonymous as possible while still reflecting the daily grind.”

The five-week shoot in early 2016 taxed everyone.

“We not only had a very tight budget, we also dealt with illness, funerals and attempted extortion,” Ms Harman said. Reflecting on this, she said it created a heightened sense of camaraderie.

What struck Ms Welham was the amount of time it takes for people to get around. “The concept of time and the impact it has on one’s life cannot be stressed enough,” she said.

“As a filmmaker, I wanted to show the tranquil pace of Miono, but also the frustration and isolation too,” Ms Welham said. Pili walks to the field for 40 minutes then walks back the same distance. To get to a health clinic where no one will recognize her from the village she has to take a bus. It breaks down on the way back so she is late to pick up her children and nearly misses her meeting with the council of women who approve micro-loans. All of this in the blistering heat.

The movie premiered in September 2017 and then played in Geneva, Switzerland, as part of the World AIDS Day celebrations on 1 December. It won two awards at the Dinard British Film Festival and was part of the official selection at the Pan African Film and Arts Festival. The movie will be screened in British cinemas in the first half of 2018, with all the proceeds being given to the Miono community.

Since filming the movie, Ms Rashid has decided that she wants to stop working in the fields and to study to become a nurse.

Ms Welham is particularly proud that the movie allows viewers to step into a world they may not know about and see that, despite the poverty, the issues remain the same. Her producer agrees. “The important part of Pili is that it’s a universal story,” Ms Harman said. “You might not be HIV-positive or live in rural Africa, but everyone can associate with wanting something better for their life and their children.”