Feature Story

Championing the cause of women living with HIV in Cambodia

15 May 2025

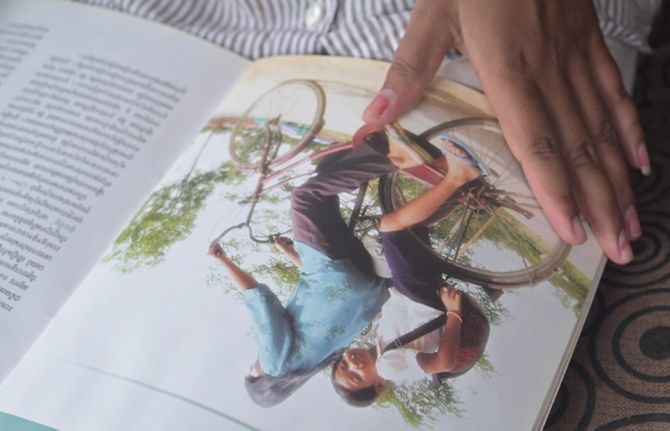

15 May 2025 15 May 2025Em Ra disappears into the house twice, slipping past the shrine of flowers and incense by the front door. First, she brings out an old HIV magazine. She flips to a page of a small child, sitting on the back seat of a bike, looking straight into the camera. Next, she emerges with two framed photographs from a recent university graduation.

The girl and the graduate are her daughter, Sorn Vichheka, twenty years apart. In 2005, the year the bicycle picture was taken, Vichheka started taking medicines. At first, she didn’t know why. When she was 12, she learned that she was born with HIV.

“I am not sure when I accepted myself fully,” she says from her verandah in Meanchey, a commune to the south of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh. “It was gradual.”

She looks out into a yard patrolled by chickens and surrounded by towering coconut trees. Under a shed in a nearby yard a baby sleeps in a hammock swung quickly back and forth by a string tied to its mother’s wrist. Vichheka’s sibling, who is HIV-negative, plays with the neighbours’ kids. They climb trees, dismounting onto the sides of concrete rainwater cisterns.

She traces her evolution from child to advocate. As a girl her mother was already involved in the HIV movement. Today Ra remains a community action worker with the Antiretroviral Users Association (AUA), helping other people at their treatment site. But as a teen, Vichheka was afraid of being found out.

“I started working for a company and did not disclose my status. At the same time, I was studying at the university. I was struggling with work and my studies, so I did not take my medicine regularly. Every time I went to the clinic co-workers would ask questions. They were curious to know what kind of health issue I had. I was very scared that people would know my HIV status,” she remembers.

Stressed, she ended up resigning from the job and dropping out of school. She soon began volunteering with an HIV organization. There, peers explained the concept of U=U (undetectable equals untransmittable) more clearly. She grasped that HIV treatment could not only keep her alive but make it impossible for her to pass the virus to others.

She also understood more clearly the issues women living with HIV were facing. Half of the people living with HIV in Cambodia are women. Five percent of women report recent intimate partner violence. Many are petrified about disclosing their status. Then there is the balancing act of self-care, family responsibility and economic survival.

“Some are housewives and need to take care of children so sometimes they don’t care much about their own health. Sometimes, because of the living conditions, they need to go to work to make an income to support the family. With this, they might miss some clinic appointments,” she explains.

Vichheka says that government social protection programmes offering free healthcare, nutrition support and cash transfers for women living with HIV have been vital. Community-led care is also required.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns when treatment access was interrupted, she joined the AUA. She participated in the community delivery of antiretrovirals for two years. After the project ended, she continued to volunteer. Between 2023 and 2024 Vichheka was driven, balancing volunteer work, daytime employment at an accounting company and evening study.

In 2023, the Cambodian Community of Women Living with HIV (CCW) — an organization that had been founded in 2008 but lost its financing in 2017— was revived thanks to small seed funding from UNAIDS for a U=U project.

That year, the Cambodian Network of People Living with HIV (CPN+) and International Community of Women Living with HIV Asia Pacific (ICWAP) mentored CCW to engage in a UNAIDS-funded Global Fund Grant Cycle 7 project. They successfully mobilized funding for 2025-2026. Vichheka was among three Cambodian participants in ICWAP’s Feminist School Leadership Training.

For the first time in over five years, CCW had a seat at the table. Vichheka was chosen by the members to be its coordinator.

“We set up a peer support group of women living with HIV who come together, share experiences and motivate one other. CCW also provides psychosocial support and connects women with job opportunities. The Global Fund investment will expand this work while conducting leadership training to build capacity among sub-national coordinators,” Vichheka explains.

Her leadership journey is a win against the odds. For her family it is also a full circle moment.

“I am really proud to have such a kind mother, taking care of me since an early age, knowing that I was born with HIV. She protected me all the time from outside society and kept me motivated,” she says.