Feature Story

Young people’s monitoring of progress towards 2025 targets begins second phase

06 April 2022

06 April 2022 06 April 2022The 2021 United Nations Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Ending Inequalities and Getting on Track to End AIDS by 2030 reaffirmed the importance of leadership by young people in the HIV response.

The Global Network of Young People Living with HIV (Y+ Global) and The PACT are two innovative networks led by young people that have consistently proved the innovation and resourcefulness of young people in the HIV response. With support from UNAIDS, they are currently rolling out the #UPROOT Scorecard 2.0, a monitoring tool led by young people, in seven countries: Burundi, Ghana, Kyrgyzstan, the Philippines, Uganda, Viet Nam and Zimbabwe.

This is the second phase of monitoring work led by young people, which started in 2017 with the #UPROOT Agenda. The scorecard process engages young people, bringing them together to assess how their country’s HIV response is working for them and if they are meeting the commitments on young people that are required to reach the 2025 HIV targets and achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3.

Tinashe Grateful Rufurwadzo, the Director of Programmes, Management and Governance at Y+ Global, has been working closely with UNAIDS on the roll-out. “Equity, inclusion and solidarity are core principles in ensuring that we end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. The #Uproot Scorecards 2.0 will continue to strengthen youth-led monitoring at the country level, further harvesting evidence for advocacy and holding our governments accountable. There is a continued need to improve the quality of care that young people living with and affected by HIV in our diversity receive and to ensure that we are all leading happy, healthy and fulfilling lives. #UPROOT Scorecard 2.0 is a platform to raise our voices and secure our future!” he said.

Ekanem Itoro, Chair of The PACT, reiterated the need for data on young people. “It is extremely crucial in the global HIV response to strengthen adolescent and youth engagement using real-time data systems and interpersonal platforms in order to positively influence knowledge, attitudes and social and behaviour change, as well as to enhance social accountability of service providers and decision-makers towards improving the quality of life of young people living with HIV and other sexual minorities.”

Young people make up 16% of the world’s population but accounted for 27% of new HIV infections in 2020. Despite the disproportionate HIV burden on young people, they continue to face age-based discrimination and exclusion from sexual and reproductive health and rights, harm reduction and HIV services. Through the completion of the scorecards, The PACT and Y+ Global aim to generate accurate qualitative data for national and grass-roots organizations led by young people to hold their governments and service providers accountable for commitments made on the health and well-being of young people. This will help catalyse advocacy on identified national priorities to achieve the targets set out in the Political Declaration on AIDS and the Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026: End Inequalities, End AIDS.

“Leadership by young people has been recognized as key to achieving the global targets that have been set, and the generation of that data will be central to scaling up the already pivotal work of networks of young people around the world,” said Suki Beavers, Director of the UNAIDS Department for Gender Equality, Human Rights and Community Engagement.

UNAIDS will continue to partner with organizations led by young people to promote youth leadership in the HIV response.

Our work

Related

“Who will protect our young people?”

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025

Feature Story

Urgently needed HIV services are supporting Ukrainian refugees in the Republic of Moldova

07 April 2022

07 April 2022 07 April 2022Many of the Ukrainian refugees seeking sanctuary in the Republic of Moldova are from Odesa or the surrounding region, which is one of the regions of Ukraine most affected by HIV.

Iryna Kvitko (not her real name) fled with her entire family, including her daughter-in-law and young grandson, to the Republic of Moldova. She said that an air-raid siren would sound several times a day, terrifying her grandson. “We thought about whether we should go or not, but it was scary to sit all night in our home—me, my husband, son, daughter-in-law and grandson—and try to explain to the child what the explosions and sounds of shooting were. Plus, to be honest, I was very afraid of the situation regarding my antiretroviral therapy—I was running out of it and it was not clear what would happen next.”

Ms Kvitko has been living with HIV for more than 15 years but keeps her diagnosis a secret. “I work, we live decently. I have a family, children, relatives, friends, colleagues. God forbid that someone would find out—it would all go to dust,” she said.

She described her difficult journey to the Republic of Moldova—there was widespread panic and at the border checkpoints the queues of traffic reached up to 80 kilometres. “Many people just got out of their cars and walked. Our main goal was to take our children and grandson out of Ukraine,” she said.

“My doctor in Odesa gave me information on where people can go to get help with antiretroviral therapy. I called them and after they took my contact number they immediately called me back and explained where to go and what to do and said that they would help me and give me the medicines I need.”

On the very first day of the war, Ihor Plamos (not his real name), together with his wife and child, drove to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa. There were a lot of people at the border, he recalled. “As soon as we got to our destination, I started to drive back to the border, to give a lift to people who had travelled on their own, who had walked seven or eight kilometres.” He took them to an aid distribution centre, from where they travelled on to Georgia or Germany.

“When we arrived, we didn’t know what to do. So, I called my doctor in Ukraine, and she told me where to go,” he said.

The clinic that his doctor referred him to tested his viral load free of charge, and the doctor prescribed antiretroviral therapy for him. He does not want anyone to know that he is living with HIV, noting that the level of stigma around the virus remains very high. “Therefore, I was worried at the beginning about what would happen to my treatment,” he said.

Hanna Brovko (not her real name) travelled to the Republic of Moldova from Odesa with her 11-year-old son, leaving behind her sewing business, clients and friends. She has been living with HIV for more than 12 years, but she does not tell people about her diagnosis. “I don’t need pity, and I don’t want things to be said about me behind my back.”

She received all the necessary medicines upon her arrival in the country but decided to move on to Germany. Berliner Aids-Hilfe helped her to arrange her flight from Chisinau to Berlin, set up her in a family’s house and arranged medical insurance, which is necessary for her to obtain her HIV treatment.

Elena Golovko, an infectious diseases doctor at the Hospital of Dermatology and Infectious Diseases in Chisinau, emphasized that people who come from Ukraine receive all HIV services in the same way that Moldovan people living with HIV do. “Today, we have a person living with HIV hospitalized, there are several HIV-positive women, there are those who have already given birth here and who received syrup to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. There is also a person receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis. We issue a 30-day supply of antiretroviral therapy to refugees. If people stay longer in the country, they can come and receive a refill. We don’t have any problems with ensuring the same level of HIV services,” she said.

However, she added that some people did not know their latest test results or could not remember the name of the medicines they take. “It was important for us to establish communication with colleagues in Ukraine, especially fast communication when a person is directly in the clinic.”

Alina Cojocari, the coordinator of assistance for people living with HIV at the Positive Initiative nongovernmental organization highlighted that it is fully involved in service delivery for refugees in need of HIV services. “We are referring people to health services, supporting them with accommodation in the country and offering them psychosocial and legal support,” she said. “For those travelling from the Republic of Moldova to other countries, we ensure they are linked to HIV services in the next country,” she added.

“This level of HIV services for refugees living with HIV in the Republic of Moldova became possible as these services in the country have long been built around people’s needs,” said Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Country Manager for the Republic of Moldova. “This approach is now also being used for refugees. During humanitarian crises, such as the war in Ukraine, everyone is vulnerable and people fear for their loved ones. For people living with HIV, there is also the fear of not receiving timely, life-saving HIV treatment, and in many cases the fear of the disclosure of their status. That is why it is so important to create sustainable, agile, equitable health and social protection systems with people at the centre, which can protect people during a crisis.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Encouraging income generation and social entrepreneurship by people living with HIV in Brazil

29 March 2022

29 March 2022 29 March 2022In the city of Recife, capital of the state of Pernambuco, in the Northeast Region of Brazil, a specially adapted bicycle carries products made by people living with HIV to be sold directly to consumers. It is called the Diversibike, one of the strategies for income generation implemented in the context of the Solidarity Kitchen, a project developed by the Posithive Prevention Working Group (GTP+) nongovernmental organization, one of the three Brazilian organizations that have benefited from resources from the UNAIDS Solidarity Fund, whose objective is to support entrepreneurial activities led by people living with HIV and key populations.

GTP+ was created in 2000 and was the first nongovernmental organization in the Northeast Region of Brazil to be led exclusively by people living with HIV. Among the projects developed by the organization, in addition to the Solidarity Kitchen, are the Espaço Posithivo, which welcomes people living with HIV who seek support, and Mercadores de Ilusões, which works to support sex workers to strengthen their self-esteem and claim their rights to citizenship.

The Solidarity Kitchen emerged in 2005, initially to produce meals for people living with HIV who sought support from GTP+. In 2019, a new element, the Confectionery School, was added to provide sex workers, ex-prisoners and other vulnerable people living with HIV with a way to generate income through cooking. With the resources received from the Solidarity Fund, GTP+ was able to boost initiatives to commercialize the products developed in the Solidarity Kitchen and train the participants in different aspects of entrepreneurship.

“The project has contributed to transforming the lives of people living with HIV in vulnerable situations. Through the project, they found an opportunity to generate income through entrepreneurial activities and developed their skills in gastronomy, learning recipes and techniques to improve their products,” said Wladimir Reis, the General Coordinator of GTP+.

Sérgio Pereira, one of the founders of GTP+ and the Coordinator of the Solidarity Kitchen, agreed, adding, “When the job market knows that we live with HIV, it doesn’t accept us. The Solidarity Kitchen brings to the participants the possibility of sustainability and opens doors for them to be able to enter the job market.”

Karen Silva, one of the beneficiaries of the Confectionery School of the Solidarity Kitchen, said, “I was welcomed at GTP+ with a lot of attention and care. First, I participated in the Posithive Space, then little by little I started helping in the kitchen and here I am. Participating in the Solidarity Kitchen changed my life and my self-esteem as well.” In total, 20 people have directly benefited from the Solidarity Kitchen, with the support of the Solidarity Fund.

As the objective of the project was on finding and promoting the best conditions for marketing products made in the Solidarity Kitchen, the team responsible for the project held weekly planning, organization and production meetings. They also conducted market research to identify the tastes and interests of potential customers, which was especially important in identifying Diversibike’s potential.

According to Mr Reis, an important part of the process of capacity- and knowledge-building of the group of project participants were the virtual trainings in gastronomy and administration offered through a partnership with the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco. Two scholarship-holders from the university supported the group in the meetings and by producing support materials.

One point to which Mr Reis draws attention is the fact that the project was born in a time of extreme social inequality. “For this reason, it is essential that we implement more initiatives like this, with support from the Solidarity Fund, so that other people in vulnerable situations can have the same development opportunities. With the project, we were able to observe the impact of generating financial resources for the participants, in addition to strengthening their knowledge to implement their projects and ensure their sustainability during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“The Solidarity Fund’s support for GTP+ highlights the importance of guaranteeing income generation by organizations led by vulnerable key populations. It is a strategic action, which generates social protection for those people, allowing them access to basic resources to take care of their health and to access HIV prevention and treatment services,” said Claudia Velasquez, the UNAIDS Country Director for Brazil.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Ukrainian activist Anastasiia Yeva Domani talks to UNAIDS about how the transgender community is coping during the war in Ukraine

30 March 2022

30 March 2022 30 March 2022Anastasiia Yeva Domani is the Director of Cohort, an expert on the Working Group of Trans People on HIV and Health in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and a representative of the transgender community on the Ukrainian National Council on HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis.

UNAIDS spoke to her to see how she and the wider transgender community are coping after the Russian attack on Ukraine.

Tell us a bit about yourself and the transgender community in Ukraine

I am the Director of Cohort, an organization for transgender people. Cohort has existed for about two years, although I have been an activist for more than six years. According to the Public Health Center of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, before the war there were about 10 000 transgender people in the country, although that number is likely to be an underestimate since many transgender people are not open about their gender identity. Many only seek help during a crisis—this was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is happening now, during the war. Today, we are receiving requests for help from people we have never heard from before, people who are in dire need of humanitarian, financial and medical assistance.

Ukraine created the most favourable environment for transgender people in the post-Soviet countries with regard to changing documentation and the legal and medical aspects of gender transition. It is far from perfect, but we and other organizations have done our best to improve it. Since 2019, transgender people have been represented on the Ukrainian National Council on HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis.

What was the situation like for transgender people at the beginning of the war?

In 2016, a new clinical protocol for medical care for gender dysphoria was adopted in Ukraine, which greatly facilitated the medical part of gender transition. Thanks to it, the next year people were able to receive certificates of gender change.

However, many transgender people have yet to change all their documentation. Some people didn’t change any, some only changed a few documents and only a few changed absolutely all of them, including driver’s licences, documents on education and those that relate to military registration and enlistment. We warned about this, and now there is a war. Many transgender people didn’t realize that they needed to be deregistered at the military registration and enlistment office.

Due to martial law, men aged 18–60 years cannot leave the territory of Ukraine if they do not have permission from the military registration and enlistment office. We have a lot of non-binary people with male documentation who cannot leave.

With the outbreak of the war, many transgender people moved to western Ukraine. But, if according to your documents you are a man, you cannot leave Ukraine.

What is the situation now and what is the focus of your work?

Because of the war, in some cities there is no one left at all. Kharkiv had the largest number of transgender activists after Kyiv, including many who moved there from the occupied Luhansk and Donetsk regions in 2014. And now they must move again. We have no information about the death of any transgender people, but I think that this is only because there is no connection with some cities, such as Mariupol. Many simply did not have time to leave the city, and then it became impossible. I’m afraid that the statistics will be terrible, it just will take time to understand what happened there.

There is a lot of work going on in Odesa now—we have two Yulias there, transgender women from whom the community receives tremendous support. They took on many issues of support and funding. In Odesa, the situation is better with hormones, with medicines. We also still have a coordinator in Dnipro—she also does a lot.

Our work is now focused on financial, medical and legal assistance to transgender people who are in Ukraine, no matter where, in western Ukraine in shelters or apartments, or staying in their cities where the bombings are. Everyone has fears, but you still need to have some kind of inner core and try to fight. I don’t think everyone should leave. I understand that many people have a grudge against society, the state. For many years, decades, they lived as a victim. There is nothing to keep many of them here—there is neither work nor housing.

Who is supporting you financially?

We had projects planned for 2022, and literally on the first or second day of the war representatives of our donors said that the money could be used not only for planned projects but also for humanitarian aid. This included RFSL, Sweden, which approached this issue in the most flexible way and allowed us not only to use the project money but also to send money directly to our coordinators, so that they themselves could pay for people’s housing, travel, etc.

Then GATE (Global Action for Trans Equality) also immediately said that their funds could be used for humanitarian aid, and promised additional funds. The Public Health Alliance, through the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, allowed changes to be made to the budget and the nature of the planned activities.

Now we will do what we can do in the context of the war, and the mobilization of the community will continue in Dnipro, Odesa, Lviv and Chernivtsi. New partners appeared that immediately responded to our needs.

I use OutRight Action funds every day for the humanitarian needs of transgender people, and also funds from LGBT Europe. There are also private donations, not large, of course, but they are also there.

What does your average day look like?

My day is filled with communication with journalists from leading publications. I also go to supermarkets for groceries and distribute them to those who need them—I have Google forms where I can see requests for help.

I administer requests for consultations with a psychologist and an endocrinologist, who continue to work in Ukraine. I receive many questions related to crossing the border and I provide information on how to communicate with the military registration and enlistment office and on which documents they need for deregistration.

There are a lot of calls, so I charge the phone five times a day. I have two Instagram accounts, two Facebooks accounts, three mail addresses, Signal, WhatsApp, etc. You need to be constantly in touch. I also need time to stand in two-hour queues at the post office—it’s such a waste of time, but people need the medicines I send. I also need to leave time to monitor the news, I need to know what is happening at the front, in the cities.

What is giving you strength?

Until my family and child left the city, I could not work in peace.

I am currently in Kyiv. In the first 10 days of the war I felt shock and fear—we literally lived from one hour to the next. Now we have got used to the danger and I’m not afraid anymore. I decided for myself, if it is destined, then so it will be. I no longer go down to the shelter: so much work, so many requests for help, calls, consultations every minute.

I was born here, in Kyiv, this is my home town. I realized that when things are bad for your country, you have to stay. I can’t run away, my conscience just won’t let me. I can’t because I know my city needs to be protected. You don’t have to be in the military to help—there is military defence, but there is also volunteer work, humanitarian aid is a lot of work.

What gives me strength? Because this is my country, I understand that everyone who can do anything, on any front, is there. We can do it everywhere, everyone can contribute, do something useful, and that gives me a sense of being needed, a sense that we can all do so much together.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

United Kingdom parliamentary group visits UNAIDS to strengthen collaboration

06 April 2022

06 April 2022 06 April 2022Members of the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on HIV and AIDS from the United Kingdom, along with the Director of Stop AIDS, visited UNAIDS Headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, to strengthen collaboration.

Since the mid-1980s, APPG has brought United Kingdom parliamentarians together from across the political divide to fight for the rights of people living with HIV.

“I think all politicians are driven by wanting to make a difference,” said David Mundell, Member of Parliament, who is Co-Chair of APPG. “This is an established all-party group that has been effective, with a voice in parliament and that also acts globally.”

Mr Mundell said that APPG is focused on maintaining momentum on HIV in the face of several challenges. Not only did some people in the United Kingdom mistakenly imagine that HIV was already sorted, he said, he also alluded to the challenges in keeping attention on HIV given the war in Ukraine and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have to be advocates for change in terms of keeping HIV high on the agenda and resources available,” he said. For example, he believes that funds for Ukraine should be additional and not come from the international development envelope and will argue that case to the United Kingdom’s Foreign Secretary.

In his words, it’s all about putting the best case forward. “There is a competition for attention, therefore we need to put issues into context,” Mr Mundell said. He mentioned UNAIDS and its Cosponsors’ Education Plus initiative as a great way to empower young women while also tackling HIV. “Demonstrating the interconnectedness of such issues will allow us to sustain our arguments.” Every week, more than 4200 young women become infected with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa but keeping girls in secondary school reduces that risk by up to 50%.

Reflecting on the United Kingdom’s decision to cut its level of official development assistance from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross domestic product and reduce funding for the AIDS response, Mr Mundell explained that there have been many ongoing changes in the United Kingdom, but he is confident in making the case that investment in the AIDS response is good value. “It is quite clear that United Kingdom funding will be more outcome-based, with a need to show direct results based on investment. APPG intends to maintain United Kingdom leadership in the AIDS response, working with community groups on the ground with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, as well as UNAIDS.”

UNAIDS and APPG reiterated their strong commitment to having a fully replenished Global Fund. Twenty years after the founding of the Global Fund, the target for the seventh replenishment is to raise US$ 18 billion to save 20 million lives. According to estimates, this represents 14% of the total of US$ 130.2 billion needed for the period 2024–2026.

Inter-Parliamentary Union Secretary-General Martin Chungong and UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima hosted a joint round table for APPG to discuss the crucial role of legislators worldwide in taking the bold actions needed to end AIDS.

“We parliamentarians from the United Kingdom cannot tell people in other countries how to run their country, that is not what we want to do,” said Mr Mundell, noting that instead the group worked to share experiences and build partnerships. He cited how criminalization has been linked to higher numbers of HIV infections, which can often lead to much more difficult, long-term consequences. “By highlighting certain practices and steps we want to show that certain changes can have a positive effect without undermining cultural values,” he said.

Mr Mundell noted that during the Commonwealth discussions in mid-March, he urged all nations to have full and frank discussions on progress in advancing the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people and progress in ending AIDS, saying that a huge amount had been achieved but that there was still a lot to do.

Suki Beavers, UNAIDS Director, Gender Equality, Human Rights and Community Engagement, commended APPG’s inclusive approach. She also stressed that the role of parliamentarians is key.

“Parliamentarians can open up the space to discussions and make diverse voices heard in the national policy process, especially the voices of people who are often excluded from decision-making on the issues that affect them most,” she said. Ms Beavers also said that strengthening peer-to-peer relations (parliamentarian to parliamentarian) can also drive progressive law reform.

Mr Chungong shared how parliamentarians from across the world are stepping up their work with UNAIDS to address the inequalities that hold back progress on ending AIDS.

In Ms Beavers’ closing remarks, she reiterated to the group the fact that the HIV response was at a critical point. “We need to move to a more targeted and systemic approach as laid out in the new Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026, including fully funded and supported community-led responses,” she said.

“It is really clear that we need major leverage to influence and to create more and more diverse partnerships so that we can achieve the goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.”

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Transgender sex workers face frequent abuse

29 March 2022

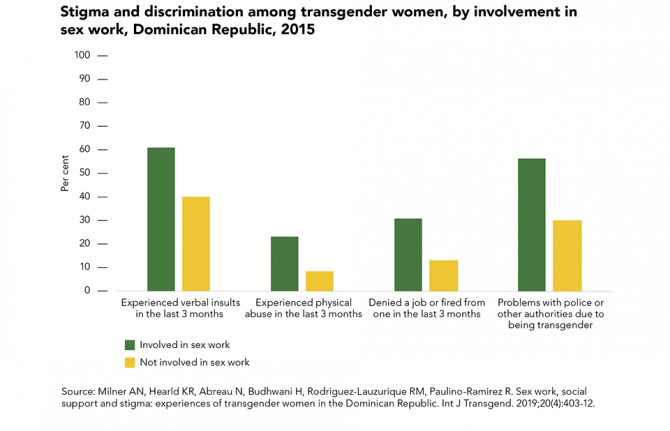

29 March 2022 29 March 2022In every region of the world, there are key populations who are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection. One of the key populations is transgender women, who are at 34 times greater risk of acquiring HIV than other adults.

Discrimination, abuse, harassment and violence are distressingly common experiences for transgender people. They often face, from a young age, stigma, discrimination and social rejection in their homes and communities for expressing their gender identity. Such discrimination, violence and criminalization prevent transgender people from getting the HIV services they need to stay healthy.

Transgender women who also are involved in sex work are even more likely to be subjected to such treatment, as shown in a study from the Dominican Republic.

Our work

Related

Feature Story

Training health-care workers in Indonesia to improve HIV services for young key populations

30 March 2022

30 March 2022 30 March 2022“Young people here don’t regularly access HIV services. I really want to invite my friends to get tested, but they are all so afraid. They don’t have enough information or support from their families and are scared about finding out their status,” said Andika Bayu Aji, a young person from West Papua, Indonesia.

The HIV epidemic among young people in Asia and the Pacific has largely been overlooked, even though about a quarter of new HIV infections in the region are among people aged 15–24 years. The vast majority of young people affected by HIV in the region are members of vulnerable populations—people living with HIV, gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers and people who inject drugs.

Like many countries in the region, Indonesia’s HIV infections among young people, which make up almost half of new infections, are attributed to stigma and discrimination, poor educational awareness of HIV, lack of youth-friendly services and social taboos.

“Young people far too often experience stigma and discrimination in health-care settings. Health-care workers are first-line responders. If the services are bad, young people won’t use them and they will tell other young people not to use them. We are limited by which clinics we can access because many, if not most, are not youth-friendly,” said Sepi Maulana Ardiansyah, who is known as Davi and is the National Coordinator for Inti Muda, the national network of young key populations in Indonesia.

A recent study conducted by Inti Muda and the University of Padjajaran found that the willingness of young people to access services in provinces like West Papua was very low, mainly due to the lack of youth-friendly services and the poor understanding of key population issues by health-care workers. Young people often face difficulty accessing services because of the remoteness of clinics and hospitals and encounter barriers such as the age of consent for testing.

Stigma and discrimination, and especially discrimination from health-care providers, discourages many young key populations from accessing HIV services. Concerns about privacy and confidentiality are some of the main challenges. Additional obstacles include that the opening hours of public clinics are often ill-suited to people’s daily routines, and the assumptions and attitudes of health-care workers can be judgemental, especially on issues around sexual orientation, gender identity and mental health.

Between 14 and 18 March, Inti Muda, with technical support from Youth LEAD and UNAIDS, organized a sensitization training of health-care workers in two cities, Sentani and Jayapura, in the West Papua region. More than 50 health-care workers participated. A few days before the training, Inti Muda organized a festival for more than 80 young people, joining in an effort to engage young people in the HIV response and generate demand for access to HIV services.

“Prior to this training, I didn’t know about the different needs of key populations, which hinders our ability to reach them. We learned about important techniques for reaching young people, such as providing youth-friendly counselling, digital interventions and encouraging them to get tested,” said Kristanti, from the District Health Office of Jayapura.

“I learned that the needs of young people are diverse. The training will allow us to improve our services to become youth-friendly, which is now our main priority,” added Hilda Rumboy, a midwife in charge of the HIV Services Department at the Waibhu Primary Health Centre.

The training and festival were supported by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). The recent investment of AU$ 9.65 million set aside by the Australian Government from the sixth replenishment of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), including DFAT funding of AU$ 2 million previously committed to UNAIDS, is aimed at reducing the annual number of new HIV infections among key populations in Cambodia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines.

“Ensuring young people and vulnerable groups have access to accurate, digestible information about how to prevent HIV, and that testing facilities are cheap and accessible, is crucial to ending the AIDS epidemic. We are proud to work with local communities and UNAIDS to increase availability of information on HIV, improve the reach and quality of medical services and encourage young people and vulnerable groups to get tested,” said Simon Ernst, Acting Minister Counsellor for Governance and Human Development at the Australian Embassy in Indonesia.

The training is based on the manual developed by Youth LEAD in 2021, which was financially supported by the Global Fund’s Sustainability of HIV Services for Key Populations in Asia Programme and the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia and the Pacific. Under the DFAT grant for the next two years, Youth LEAD will expand the training to two more countries, Cambodia and the Philippines, supporting networks led by young people in the respective countries to roll out the training.

“Young people still encounter many challenges that prevent them from accessing the life-saving health care they need. The UNAIDS Country Office for Indonesia is working closely with the UNAIDS regional support team and DFAT to ensure that networks led by young people have the capacity and leadership capabilities to take control of the HIV response and to have direct involvement in creating safe spaces where young people can access HIV services free from stigma and discrimination,” said Krittayawan Boonto, the UNAIDS Country Director for Indonesia.

Our work

Region/country

Feature Story

Helping to break stigma and discrimination against transgender people in Brazil

31 March 2022

31 March 2022 31 March 2022Una is a coastal city of just over 20 000 inhabitants in the Brazilian state of Bahia. Fourteen years ago, Rihanna Borges left her little piece of paradise behind, to arrive at a much larger metropolis: São Paulo. “I needed to be reborn as a person and have the freedom to be who I really was. I wanted to be Rihanna, this trans woman whose essence could not safely emerge in my home town.”

Her decision reflects the decisions made by many transgender people, who, at some point, need to move away from their families to live life fully. When she recognized herself as a transgender woman, she had her mother’s unspoken support and recognition, but got no support from her father, triggering conflict and rejection that brought her a lot of suffering.

“Imagine coming out in a small town, with deep conservative and sexist roots. I could suffer any kind of violence. When I left Una I knew I was not that person my father expected. I had to leave my roots and throw myself into the world, so that I could be entirely me,” said Ms Borges. She has now reconciled with her father and has, in her words, a “nice” relationship with her family.

“Stigma and discrimination steals our identity as human beings, destroying us, turning us into unimportant people, who can be abused, mistreated, violated. So, the support of our families is critical because the world outside is cruel and destructive,” she said.

Ms Borges is one of the residents of Casa Florescer, a pioneering transgender welcoming centre located in the city of São Paulo, which hosts them while providing housing and access to mental health and other health-care support. Owing to increased vulnerabilities, stigma and discrimination, inequalities and disrupted family ties, among other reasons, the transgender women served by Casa Florescer come from extremely vulnerable backgrounds, having a history of adopting, and being exposed to, higher risk behaviours, including unsafe sex and use of drugs.

In this context, UNAIDS launched in 2021 an innovative initiative, the FRESH Project, to engage transgender women in understanding combination HIV prevention, focusing on pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis and harm reduction. Through the project, the participants are rewarded for positive behaviour change to reinforce positive behaviours and reduce their vulnerability and the impact of inequalities.

The first initiative of the FRESH Project in Brazil saw the voluntary participation of 22 of the 30 transgender women residents of the Casa Florescer, including Ms Borges.

The participants were trained in photography in sessions promoted by the American photographer Sean Black, who specializes in portraying lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people, especially people living with HIV. During the sessions, the participants reflected on their daily lives through their photographs.

“It was incredible to realize, over the days, how many of the women had a very negative opinion of themselves, reflecting the stigma they suffer from society. They discovered themselves as the beautiful and unique people they are and understood how fundamental it is to take care of themselves,” said Mr Black. “The photographs that I took, and the ones that they also took, reveal the essence of each one of them and how they are people who dream and want to be happy, like everyone else,” he added.

Ariadne Ribeiro Ferreira, the UNAIDS Brazil Community, Gender and Human Rights Officer, who is a transgender woman, highlighted that one of the objectives of the FRESH Project was to show that transgender sisterhood also means strengthening the path of self-respect, self-love and self-care. “Stigma and discrimination, associated with society’s punitive logic, only increases the social abyss that the most vulnerable groups are forced to face. Therefore, positive reinforcement, in this case represented by photographic art, is transformative and a path to a process of personal and collective change.”

“When I saw my photos after the photography sessions, I realized how powerful is to show our essence, the beauty that each one of us has. I felt it strengthened in me the certainty of how important it is, first of all, that we take care of ourselves, love ourselves, in order to pass this love on to other people and face stigma and discrimination,” said Ms Borges.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises”

23 March 2022

23 March 2022 23 March 2022Yana Panfilova is Ukrainian and was born with HIV. When she was 16 years old, she created Teenergizer, a civil society organization to support adolescents and young people living with HIV in Ukraine. Since 2016, Teenergizer has been working internationally, promoting the rights of teenagers and young people in Ukraine and in seven cities in five countries across eastern Europe and central Asia. In 2019, the organization began providing peer counseling and psychological support to adolescents, and has trained more than 120 online consultants–psychologists to support young people across the region. In June 2021, she spoke at the opening of the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on AIDS. When the war in Ukraine started, she left Kyiv, Ukraine, with her family and made her way to Berlin, Germany, from where she is continuing her work to support young people living with HIV in Ukraine.

Why and how did you leave Kyiv?

Within days of the start of the Russian invasion I understood that we needed to make a life-changing decision—people with machine guns were patrolling the streets. I had to convince my mother that we needed to leave, because she was reluctant to go. We packed up our lives in less than an hour, drove to Kyiv railway station, left our car there and boarded the first train that we could find. There were so many people, mothers, children, and fathers and brothers seeing off their families, and many people were panicking. We had to stand on the train for 12 hours, with our suitcases and our cat. When our grandmother caught up with us at our first stop, we travelled together from Ukraine, along with her dog, crossed the border to Poland and went on to Berlin. The entire trip took seven days. It was the longest and most challenging trip of my life—I didn’t want to leave my beautiful Kyiv not knowing where we would end up. Now we are here in Berlin, refugees, safe and secure, but still in disbelief about what we have been through and distraught about what is happening to the people of Ukraine. But at least we are safe and together—my mother, my grandmother and her dog, and me and my cat. I was lucky that I brought enough antiretroviral therapy to last about two months.

Are you settled in Berlin?

I’m still in limbo, like millions of other Ukrainian women and children who have made this journey. But everyone we have met at every step of this journey has been so kind and welcoming. We are now clarifying the legal aspects of how to stay here in Berlin for the next few weeks and how we can access local medical and social services. Even how we can rent an apartment is still not yet clear. We made an appointment online with the municipality of Berlin to clarify the details with them. They are working to provide me with medical insurance so I can get access to medical care and uninterrupted access to HIV treatment.

I am also in contact with Berliner Aids-Hilfe, one of the oldest nongovernmental HIV organizations in Europe; after the war in the former Yugoslavia, they have a lot of experience in working with migrants living with HIV. They have been amazing, ready to help with access to antiretroviral therapy as well as the other needs that Ukrainians living with HIV will have here in Berlin.

So, you're more or less safe now. How are the other young people from Teenergizer doing?

Most of our teenagers living with HIV have already left Ukraine and now they are in Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, Poland and other countries. We are in contact with most of them every day. Some of our activists chose to stay with their parents in Kyiv and other cities that are under attack. We are now clarifying the latest information and trying to monitor where everyone is, and if they are safe. But this is not a quick or easy process. Everyone is now trying just to survive and stay in contact. Our staff, peer educators and clients are now scattered across different countries, each with different laws, treatment regimens and access to the Internet. Those still in Kyiv are connected with our partners, who are still providing access to antiretroviral therapy and emergency humanitarian assistance. Most of our consultants–psychologists are still providing online assistance to those in most in need.

What are the issues you are dealing with to stay in Berlin?

The people here in Berlin and all the Germans we have met since we arrived have been incredibly kind and welcoming. We are very grateful. I know all cities across Europe are struggling to support millions of Ukrainians, but I don’t think we could have found a safer and more tolerant place to stay than Berlin.

Of course, our most urgent questions are of a legal nature related to temporary status here and, second, questions about access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy. Third is housing. I never thought housing would be so important or so nerve-wracking. Local volunteers are helping around the clock, and millions of Europeans have opened up their homes. But for the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians still living in warehouses, shelters and other temporary accommodation, the lack of a place you can call a temporary home can crush your spirit.

What do you think is most important to keep doing now?

No matter what happens with the war, we have to continue supporting each other in the Teenergizer family. In Ukraine, we spent years fighting so that young people living with HIV could have our health and rights protected. And now it feels like so many of our hard-won gains have disappeared overnight. In the middle of this crisis, we have to keep standing up for our rights and focus on the urgent needs facing the most vulnerable members of our Teenergizer network. I am so lucky to be alive and here in the safety of Germany. But many of our friends are still in Kyiv and in other cities across Ukraine, fighting for their lives and our country. Some of them have no way out and others don’t want to leave their homes and their families. Now, more than ever, they need our support and reassurance that we will continue to do everything we can to support them when they need it most.

First, we need to help them to navigate this new crisis and continue life-saving services—HIV treatment for those who urgently need it, and prevention and testing services. Second, during this crisis, we must continue to provide young people with mental health services, especially peer counselling. In our region, HIV is more of a social problem than a health problem. Today, young Ukrainians living with HIV are facing the triple crises of their health, their safety and acute stress and depression caused by the war. Psychologists call it PTSD. This trauma is continuing for an entire generation of Ukrainians. Young people who need professional psychological support will start using drugs and some of them will contract HIV, but they will be too scared or ashamed to ask for help in the current crisis. The same applies to adolescent girls and women who cannot exercise their reproductive and sexual rights, or young people who do not use a condom during sex, or millions of Ukrainian women who are at risk of exploitation when they are alone in Europe, away from their families and friends. Today, thousands of adolescents still in Ukraine who are living with HIV are afraid to reveal their status. Many still do not know how to protect themselves from HIV and from the violence of war. Millions of Ukrainian youth are left alone to cope with their anxieties and fears, and an entire generation will be dealing with post-traumatic disorders—this needs urgent attention. I am convinced that if we provide even basic counselling and support now, young people facing multiple crises will be better able to cope with their problems for years to come.

And also no matter what, we have to push politicians to listen to young people and allow them to influence the decision-making process about their own health and future. The voices of young people, especially young women, should be heard to stop the war and rebuild Ukraine.

How do you see the future of Teenergizer now?

Today, me, my family and my country are facing the greatest crisis of our lives. So if I am not sure about tomorrow, it is difficult to see what the future holds. Over the years, we built a real family, teams of young Teenergizer leaders in different cities in eastern Europe and central Asia—in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, even in Russia. But now we are divided. After the Second World War, Winston Churchill said that there would be a wall. And I think that a new wall is appearing now.

What would you say today if you were again on the podium of the United Nations General Assembly?

This is a war between the old world and the new world.

We are young people who want to live in a new world, where there are no wars, where pandemics such as HIV, tuberculosis and COVID-19 are ended, where poverty and climate change are solved. In this new world, all people, no matter who they are or who they love, whatever language they speak or what passport they hold, can enjoy freedom and live their life with dignity, and travel and move across open borders, between peaceful countries. We learned how important and precious this was in recent years when Ukrainians could travel. We could see how peace-loving people lived in other parts of the world, and it made us appreciate the beauty and freedom we have in Ukraine. Today, more than ever, we only understand what we want to rebuild in our own country when we compare it to the values we find in other countries.

And it is this old world that is financing and sustaining this war. This is a road to nowhere.

With the billions spent on this senseless war, the world could find a cure for HIV, end poverty and solve other humanitarian crises.

The new world is about development, not destruction. It is about being able to improve yourself, improve the quality of your life and really support others to do the same.

Everything has an end. And the war will eventually end. What will you do on the first day after the end of the war?

I'll start to read Leo Tolstoy’s book War and peace.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Working together to help refugees in the Republic of Moldova

24 March 2022

24 March 2022 24 March 2022At the start of the invasion of Ukraine, the government of the neighbouring Republic of Moldova estimated that there might be around 300 000 people fleeing to the country from Ukraine. That estimate has now increased to 1 million refugees—a huge amount for a country that has a population of only 2.6 million and is one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Soon after the start of the war, a number of humanitarian organizations, United Nations agencies and civil society partners, coordinated by the government, formed response coordination groups and started to address the most acute needs of the people fleeing the war, including shelter, food, health, social protection, the prevention of gender-based violence and mental health support.

“First, we must focus on the basic needs. A lot is yet to be done around coordination with the many humanitarian organizations joining the response. Because this is also the first time ever for Moldovans to face a crisis of this size, we are learning by doing and learning from experience,” said Iurie Climasevschi, the National AIDS Coordinator at the Hospital of Dermatology and Communicable Diseases in the Republic of Moldova.

Svetlana Plamadeala, the UNAIDS Country Manager for the Republic of Moldova, visited several displacement centres near the border of Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova. “People are well-received there, the government is ensuring accommodation and food and trying to ensure that children attend school and kindergarten, as about 75% of the refugees are women and children—there are about 40 000 children under 18 years old in the centres,” she said.

According to Ms Plamadeala, almost half of the refugees are being accommodated by families in their homes. “We see the extraordinary mobilization of ordinary people, who are providing remarkable support to people who are fleeing from the war,” she said.

The government’s policy is that Ukrainian refugees will receive the same services as Moldovans, including HIV-related services. “If any of the refugees ask for antiretroviral therapy, we provide it to anyone. We will not refuse anyone if we can help them,” said Mr Climasevschi.

“UNAIDS was part of the planning process right from the very beginning of the crisis to ensure that refugees have access to all HIV-related services that Moldovan people have, including antiretroviral therapy, opioid substitution therapy and HIV and tuberculosis testing,” said Ms Plamadeala. “Stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV is still high. Perhaps not all people living with HIV have been able to access the services, so we are engaging with our civil society partners to proactively provide information to people so they know where to go for support.”

Ruslan Poverga, from the Initiativa Pozitiva nongovernmental organization, said that the organization is already identifying refugees in need of antiretroviral therapy and is referring them to support. “We’ve started proactively informing people, and, if required, providing an integrated package of HIV prevention services, including HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis testing and screening, and the provision of harm reduction and condoms. We will understand the need for such services more clearly in the near future.”

The UNAIDS Country Office for the Republic of Moldova has reallocated funds for urgent humanitarian response needs. This will increase the capacity of the National AIDS Programme to provide antiretroviral therapy to a much larger number of refugees living with HIV. Viral load testing is available to check viral loads if a change of treatment regime is necessary.

“The situation is evolving. We monitor the situation very carefully to understand when and how to look for more support. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is ready to make reallocations if they are needed, and the Republic of Moldova is able to access resources from the Global Fund’s emergency fund. In the event that the National AIDS Programme would be not able to cover the needs, we will look for more support from the Global Fund, UNAIDS, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization,” added Ms Plamadeala.