The drop-in centre of the Uganda Harm Reduction Network (UHRN) looks lonely from the deserted suburban pavement. It is a non-descript house, hidden behind an imposing solid pink steel gate, in an equally non-descript neighbourhood.

It looks like so many other drop-in centres in eastern Africa that serve key populations—anonymous and low-key. Necessary characteristics, perhaps, in a region that mostly criminalizes people who use drugs, gay men and other men who have sex with men, sex workers and transgender people.

Once through the gate, visitors are greeted with a hive of activity that belies the quiet exterior. Clients and staff are buzzing around, setting up chairs under the makeshift gazebo in the verdant garden. In a few minutes, a group of people who use drugs will take part in a harm reduction workshop run by one of the centre’s staff. There is also a consulting room at the front of the drop-in centre; and at the back, is the office of Wamala Twaibu.

Mr Twaibu is the founder and chairperson of the Eastern Africa Harm Reduction Network and UHRN. A self-styled “former drug user with roots in Uganda and the pioneer of the harm reduction movement in eastern Africa,” Mr Twaibu has a kind face and a penetrating gaze that tells a story of adversity, resilience and triumph.

In the consulting room, 25-year-old Kemigisa Sandriano, a heroin user and sex worker, is taking an HIV test conducted by the centre’s resident doctor, Mukiibi Grace Nickolas. The night before, Ms Sandriano was assaulted by a client after he took off the condom during sex. She protested, telling him to leave. Her swollen, bloodshot right eye attests to what happened after that. She is smiley and talkative, seemingly unbothered by yet another instance of violence at the hands of a client. She is happy that in his battle to get his money back, she won.

Ms Sandriano was introduced to heroin by her ex-husband, who she says “ruined” her life. Nevertheless, she is upbeat about her recovery.

“I have the hope that I can stop. I even went to rehab for three months. When I saw my days of rehab coming to an end, I saw no plan and I started again,” she says.

“I am ready to go to rehab again,” she continues. “But when I come out, I don’t want to be idle. When they take us out of rehab, we need a job. They can say to us, “Work in a supermarket, work in this shop, so you can stabilize.””

Employment aside, Mr Twaibu says medically assisted treatment for people with opioid dependence is critical for rehabilitation. And, since, December 2020, with advocacy from UHRN and financial support from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the first medically assisted treatment services in Uganda have been available at the Butabika National Mental Referral Hospital in Kampala.

UHRN screens and provides initial preparation for eligible clients and refers and links them to the hospital and provides them with ongoing psychosocial support services. In December 2020, there were 81 people who use drugs enrolled in medically assisted treatment.

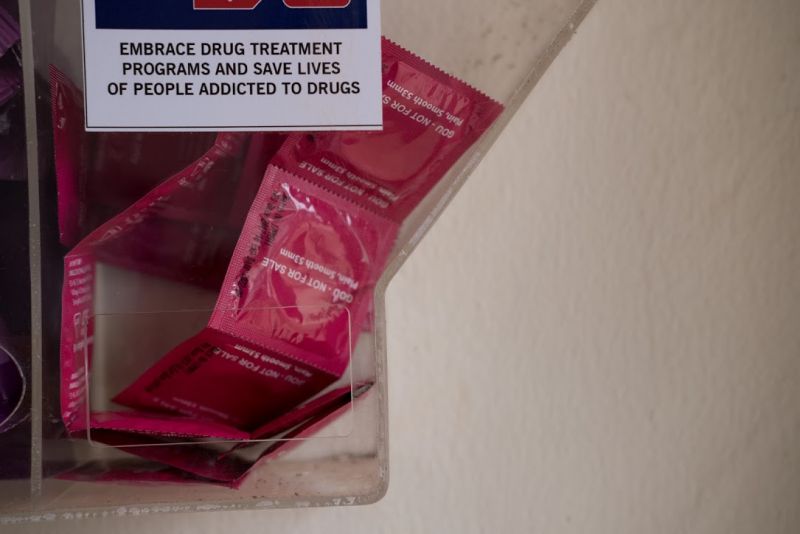

Besides medically assisted treatment, through its drop-in centre UHRN offers a comprehensive package of health services, including behaviour change communication, a needle–syringe programme, psychosocial support, overdose management, HIV testing and counselling and sexually transmitted infection screening.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a major challenge to UHRN’s clients, who even under normal circumstances face high levels of stigma and discrimination, police abuse and harassment, alienation and limited access to health and social services.

Sex workers, transgender men and women, people who use drugs and gay men lost livelihoods and faced even more violence and detention under the guise of lockdown measures. Movement was severely limited as motor vehicles required a special permit to operate.

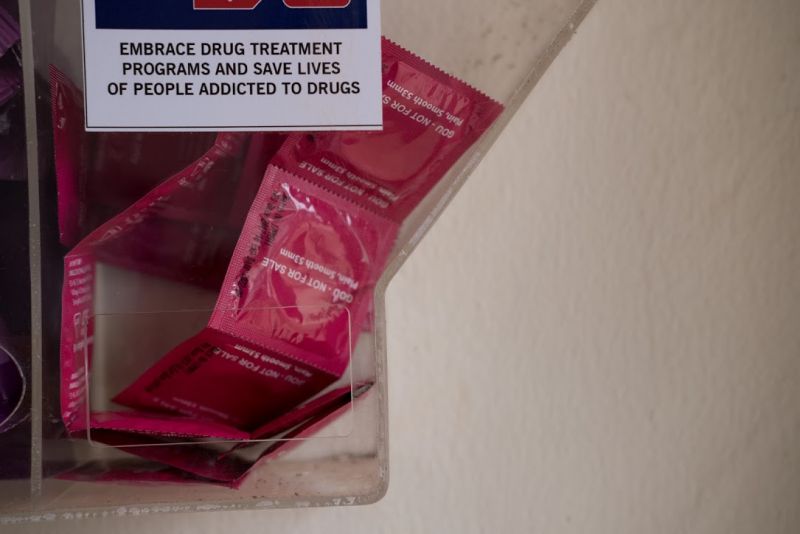

UHRN rose to the challenge. A team of 25 peer educators used bicycles, funded by Frontline AIDS, and motorcycles to reach their clients where they were, providing antiretroviral medicine refills and condoms to clients who could not reach health facilities.

The organization rolled out virtual counselling services on risk reduction and addiction management through phone calls and WhatsApp. As part of personal protective equipment procurement, UNAIDS, through the National Forum of People Living with HIV/AIDS Networks in Uganda, provided soap and bleach to prevent COVID-19 infection among the drop-in centre’s dedicated staff, who worked right through the pandemic.

Despite the constraints of the pandemic, UHRN’s needle–syringe programme reached 287 clients in 2020, providing more than 15 000 clean needles and syringes, tourniquets, cotton balls, swabs, water ampoules, condoms, lubricant and safe-injecting information notes.

“I’m proud that harm reduction issues are taking a centre stage in Uganda,” says Mr Twaibu. “Community-led means ownership. Usually when the community is at the centre, accountability and community needs are prioritized,” he says.