VIENNA/GENEVA, 15 March 2019—A coalition of United Nations Member States, United Nations entities and leading human rights experts meeting at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna, Austria, today launched a landmark set of international legal standards to transform and reshape global responses to the world drug problem.

The International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy introduce a comprehensive catalogue of human rights standards. Grounded in decades of evidence, they are a guide for governments to develop human rights compliant drug policies, covering the spectrum from cultivation to consumption. Harnessing the universal nature of human rights, the document covers a range of policy areas, from development to criminal justice to public health.

The guidelines come at an important moment, when high-level government representatives are convening at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs to shape a new global strategy on drugs. Under the mounting weight of evidence that shows the systemic failures of the dominant punitive paradigm, including widespread human rights violations, governments are facing growing calls to shift course.

“Drug control policies intersect with much of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the pledge by Member States to leave no one behind. Approaches that violate human rights and fail to curb the illicit drug trade are leaving a trail of human suffering,” said Mandeep Dhaliwal, Director of the United Nations Development Programme’s HIV, Health and Development Group. “For countries who are ready to place human dignity and sustainable development at the heart of their drug control policy, these guidelines offer valuable guidance to promote more effective and humane drug control policy.”

Seeking to promote the rule of law, the guidelines feature recommendations across the administration of justice—including discriminatory policing practices, arbitrary arrest and detention and decriminalization of drugs for personal use—and articulate the global state of human rights law in relation to drug policy, which includes ending the death penalty for drug-related offences.

At least 25 national governments—from Argentina to South Africa—have scrapped criminal penalties for the possession of drugs for personal non-medical use, either in law or in practice, setting an example for others to follow. The United Nations system has jointly called for decriminalization as an alternative to conviction and punishment in appropriate cases.

“Punishment and exclusion have been instrumental to the war on drugs,” said Judy Chang, Executive Director of the International Network of People who Use Drugs. “The time has come to privilege human dignity over social isolation and champion human rights, putting an end to the shameful legacy of mass incarceration.”

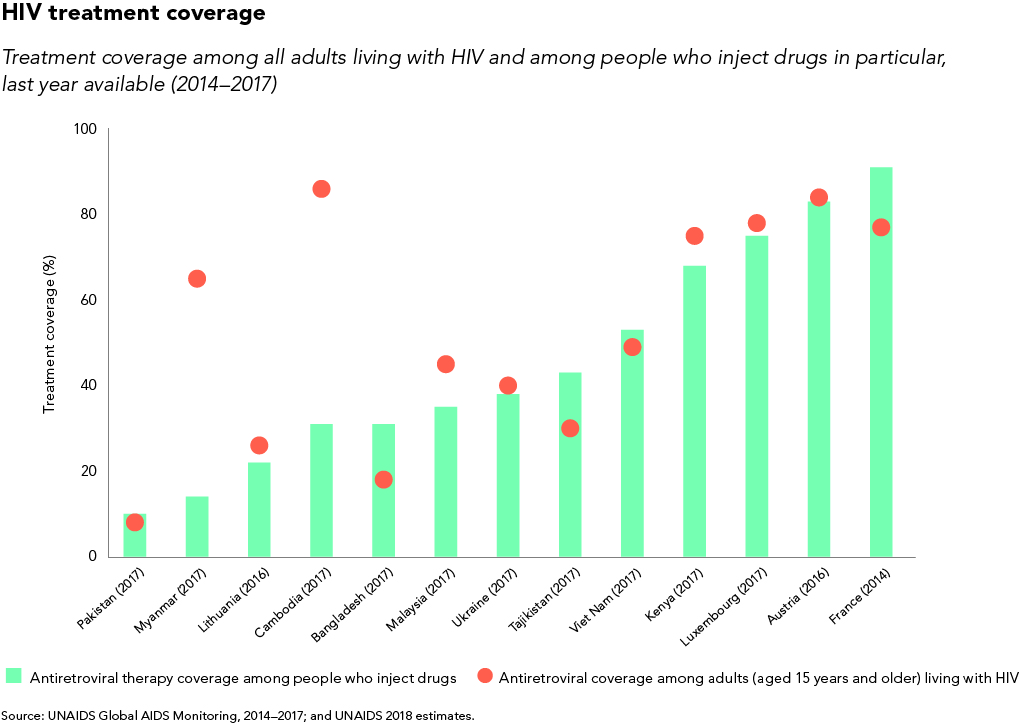

Beyond moving away from a punitive approach to drugs, the guidelines make clear that a human rights approach is critical in improving people’s enjoyment of the right to health, to live free from torture and to an adequate standard of living. In accordance with their right to health obligations, countries should ensure the availability and accessibility of harm reduction services, which should be adequately funded, appropriate for the needs of vulnerable groups and respectful of human dignity.

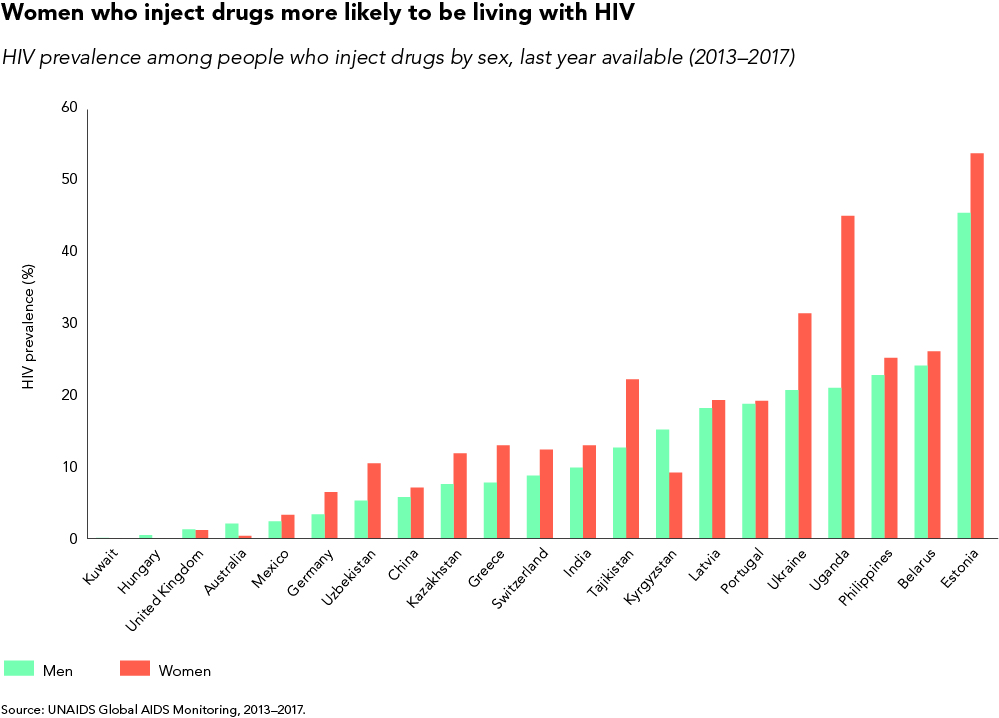

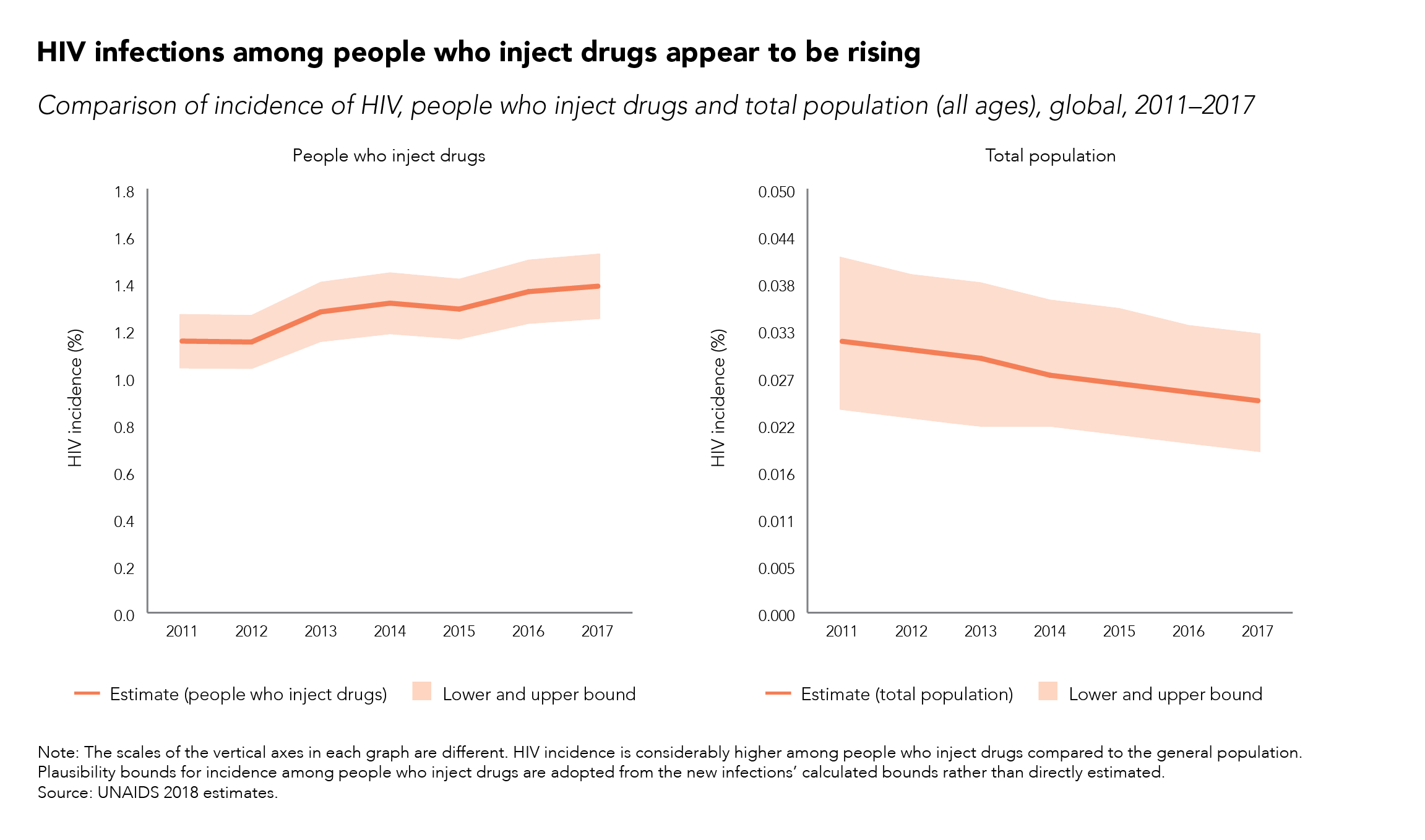

“Ninety-nine per cent of people who inject drugs do not have adequate access to harm reduction services and are left behind in the progress against HIV,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “More than 12% of people who inject drugs are living with HIV and over half have hepatitis C. The only way to advance progress is to put people at the centre, not drugs.”

The guidelines highlight the importance of protecting the rights of farming communities—especially women—to arable land. Consistent with international standards, they suggest that governments temporarily permit the cultivation of illicit drug crops when necessary to allow for smooth transitions to more sustainable livelihoods. Thailand’s success in supporting opium famers to transition to alternative livelihoods is one such example.

“Human rights should not just inform critiques of the response to drugs worldwide, they should also be the main drivers of its reform, underpinning checks and balances to break cycles of abuse,” said Julie Hannah, Director of the International Centre on Human Rights and Drug Policy, University of Essex, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. “Fighting inequality and injustice is a more effective way of addressing the global drug problem than prisons and police,” she added.

The guidelines will support United Nations Member States, multilateral organizations and civil society to integrate the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into national and global policy-making.

UNDP

UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build nations that can withstand crisis, and drive and sustain the kind of growth that improves the quality of life for everyone. On the ground in nearly 170 countries and territories, we offer global perspective and local insight to help empower lives and build resilient nations. www.undp.org.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.