Feature Story

International Women's Day: Ending Impunity for Violence Against Women

08 March 2007

08 March 2007 08 March 2007During a visit to Bangkok, Thailand, UNAIDS Executive Director Dr Peter Piot met with the Prime Minister of Thailand and celebrated the International Women’s Day with the Executive Secretary of United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific and with Ms. Joana Merlin-Scholtes, the United Nations Resident Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative in Thailand.

Dr Piot also released a statement stressing the importance of addressing gender inequality and the feminization of the AIDS epidemics. “Women, inside and outside the home, must have the economic, social and political power to stand up for their rights and protect themselves and their families from violence and disease.” He also stated that “to stop the feminization of the epidemic, as well as the epidemic itself, we have to initiate legal but also social, cultural and economic changes to challenge some of the most pervasive social patterns and gender norms that continue to fuel the AIDS epidemic.”

|

UNAIDS Executive Director, Dr.Peter Piot during his meeting with General Surayud Chulanont, Prime Minister of Thailand at the Government House (Thai koo Fah building). 8 March 2007 |

|

UNAIDS Executive Director, Dr. Peter Piot talks to Ms. Joana Merlin-Scholtes, UN Resident Coordinator Thailand at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand during the International Women's Day, 8 March 2007 |

|

From L to R: Ms. Joana Merlin-Scholtes, UN Resident Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative in Thailand, Dr. Peter Piot, Executive Director UNAIDS and Mr. Kim Hak-Su, UN Under Secretary General and Executive Secretary UNESCAP during the International Women's Day 2007 held at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. 8 March 2007. |

|

|

From L to R: Dr. Peter Piot, Executive Director UNAIDS, Ms. Joana Merlin-Scholtes, UN Resident Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative Thailand, Mr. Kim Hak-Su, UN Under Secretary General and Executive Secretary UNESCAP, Ms. Jean D'Cunha, Regional Programme Director of UNIFEM (East and Southeast Asia) and Ms. Thelma Kay, Director of the Division of Emerging Social Issues, UNESCAP during the opening session of events for the International Women's Day. United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. 8 March 2007 |

|

Mr. Kim Hak-Su, UN Under Secretary General and Executive Secretary UNESCAP during his opening statement for the International Women's Day 2007, at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. 8 March 2007 |

|

UNAIDS Executive Director, Dr. Peter Piot during his intervention for the International Women's Day 2007, at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. 8 March 2007 |

|

Ms. Thelma Kay, Director of the Division of Emerging Social Issues, UNESCAP during the International Women's Day 2007 event held at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand on 8 March 2007 |

|

Ms. Jean D'Cunha, Regional Programme Director of UNIFEM (East and Southeast Asia) during the ceremony held at the United Nations Conference Centre, Bangkok, Thailand for the International Women's Day 2007. 8 March 2007. |

All photo credit at United Nations Conference Centre: Daniel Tshin

Links:

Read UNAIDS Executive Director's statement - Addressing gender and AIDS: a compulsory requirement

Feature Story

International Women’s Day: an interview with Purnima Mane

08 March 2007

08 March 2007 08 March 2007

Purnima is a renowned social scientist and an expert in gender issues in international health, especially in AIDS. Purnima worked for over 12 years as an Associate Professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India before she joined the Global Programme on AIDS at the World Health Organization in Geneva in 1994. At UNAIDS, she pioneered work on gender and AIDS and managed the Executive Office until 1999. After working for the Population Council in New York in 1999 and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Purnima returned to UNAIDS in 2004 as Director of Policy, Evidence and Partnerships. She has co-authored and edited four books including one of the first books on social and cultural aspects of AIDS in India and is a founder-editor of the journal, Culture, Health and Sexuality. On International Women’s Day, Purnima reminds us how women are more vulnerable to HIV and how violence against women increases their vulnerability.

Dear Purnima, today is International Women’s day. Can you tell us how and why women are particularly affected by the AIDS epidemic?

Women represent almost half of people living with HIV. According to the latest data available, 17.7 million adult women are now living with HIV. This is more than ever before and the trends suggest that this number is on the rise. Everyday, 7000 women become infected with HIV. The expression “feminization of the epidemic” does not nearly catch the enormity of the situation…Nearly 25 years into the epidemic, gender inequality remains one of the major drivers of HIV. Yet current AIDS responses do not, on the whole, tackle the social, cultural and economic factors that make women more vulnerable to HIV, and that unduly burden them with the epidemic’s consequences. Women and girls have less access to education and HIV information, tend not to enjoy equality in marriage and sexual relations, and remain the primary caretakers of family and community members suffering from AIDS-related illnesses. When infected with HIV, women are more likely to be deprived of treatment and more likely to face discrimination . To be more effective, AIDS responses must address the factors that continue to put women at risk.

What would be in your opinion, the top priority intervention to reduce women’s risk to HIV?

'No one solution is obviously enough but if I had to choose one, I'd say education is critical. Sending all girls to school and making sure that they complete high school must become a collective top priority. With each additional year of education, girls acquire vital life skills and higher income-earning potential. Girls who complete secondary education know more about HIV – both how to prevent infection and what to do if they think they are infected. They tend to have fewer sexual partners over a lifetime and are more likely to use condoms. And by providing women with more economic options and independence, education gives them vital knowledge, skills, and opportunities. This means they can make informed choices about delaying marriage and childbearing, having healthier babies and avoiding risky behaviour – as well as knowing more about their rights.

The theme of this year’s International Women’s Day is Ending Impunity for Violence Against Women can you tell us more about the issue?

Violence against women continues to be a common, yet widely ignored phenomenon that robs women worldwide of their health, well-being and lives. In many places, violence against women and HIV risk are intertwined.

The most prevalent forms of violence against women are perpetrated by their intimate partners. A staggering 40–60% of women surveyed in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru, Samoa, Thailand and United Republic of Tanzania said they had been physically and/or sexually abused by their partners. Laws for protecting women from such abuse are either lacking, too weak or too poorly enforced to make much of a difference. Social norms in many countries condone domestic violence as a private, even normal matter—leaving millions of women without hope of legal recourse. But there is nothing natural or inevitable about violence against women. Attitudes can and must be changed.

How does violence against women increase risk of HIV infection?

Violence against women is often associated with a heightened risk of HIV infection. Studies in South Africa and Tanzania show that women who have been subjected to violence are up to three times more likely to be HIV-infected than women who have not experienced violence.

Violence—even the fear of violence—also prevents many women and girls from learning or disclosing their HIV status, or accessing essential AIDS services. In Cambodia, the fear of domestic violence appears to be one of the reasons why unexpectedly low numbers of women have been using HIV counselling and testing services at some antenatal clinics. At a clinic in Zambia, some 60% of women eligible for free antiretroviral treatment opted out of treatment, partly because they feared violence and abandonment if they were to disclose their HIV status to their partners. Fear of violence also prevents women from demanding protection or negotiating safer sex.

What is happening to help reduce violence against women?

Promising initiatives are under way to help reduce violence against women. Some, like Stepping Stones, now active in almost 30 countries, and Men as Partners in South Africa, use community-based workshops to challenge gender stereotypes and reshape power relations. Others, such as the Gender Violence Recovery Center in Kenya and the Cambodian Women’s Crisis Center, provide shelters, medical services and counselling, including HIV services or referrals, to women who have experienced domestic violence and sexual abuse. Such efforts must be expanded, supported and incorporated into national AIDS strategies. Governments the world over have committed to eliminate violence against women. It’s time to do more.

What are immediate measures that would help reduce violence against women and reduce their risk to HIV?

Governments must enact and enforce laws that prevent violence against women. In parallel, they must also develop strategies and approaches to ensure that those who uphold the law—civil servants, police, judiciary, healthcare workers, social services etc.—implement it in fact, and to support the victims of violence. We must also develop and fund community-based programmes to help change social norms that condone violence against women and perpetuate its acceptability. This includes educating women, men, boys and community leaders about the rights of women, and the need to change menacing norms of masculinity.

We must also work to expand women’s access to support services and economic resources so that they can escape and recover from abusive and life threatening relationships.

It’s important that national AIDS plans integrate strategies to reduce violence against women, and link violence prevention efforts with mainstream HIV prevention and treatment services.

Links:

View feature documentary "Women are 2… Finding Solutions"

Feature Story

International experts review male circumcision

07 March 2007

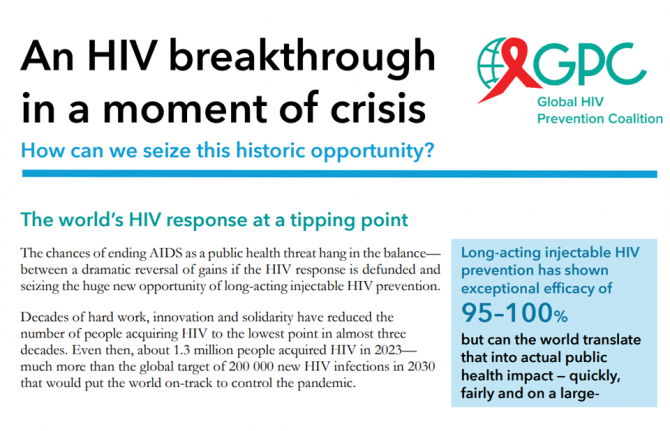

07 March 2007 07 March 2007Experts from across the world are gathering this week in Montreux in Switzerland to review the results of recent trials establishing that male circumcision reduces by almost 60% the risk of men to acquire HIV during vaginal sex. These results announced in December 2006 and detailed in recent publications in The Lancet sparked interest and debate in the world of HIV. Is male circumcision as significant an advance as some of its proponents have claimed?

Dr Kim Dickson, from the HIV Department of the World Health Organization is a recognized and respected figure in the field of reproductive health and HIV. She currently coordinates the joint WHO/UNAIDS working group on male circumcision and HIV prevention as well as the Inter-agency Task Team on male circumcision and HIV prevention. She has kindly agreed to tell us more about the meeting and its expected outcomes.

Unaids.org: Dr Dickson, you coordinate the joint WHO/UNAIDS working group on male circumcision and HIV prevention. Can you tell us why WHO and UNAIDS are convening this meeting on male circumcision?

KD: When the US National Institutes of Health decided, in December 2006, to stop the two trials they were funding in Kenya and Uganda on male circumcision and HIV, it became clear that we needed to assess male circumcision as a potential public health intervention in the response to AIDS. The trials, as detailed in the results recently published in The Lancet, confirmed many previous observational studies which suggested that male circumcision significantly reduced the risk of men in acquiring HIV during vaginal sex.

It was important that the World Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS review the research results and consider what they mean for HIV prevention policy and programming in countries. It was decided to convene a meeting to bring around the table as many stakeholders as possible to look at and discuss many of the issues that male circumcision can raise, and, if possible, give guidance and recommendations for Member States and other stakeholders.

Unaids.org: How many participants are joining in this meeting and what do they represent?

KD: We invited the trials' investigators to present their methodology and their results. We also invited other scientists, from different disciplines such as social science, human rights and communications to ask the investigators questions which were not necessarily in the scope of their trials. We also have 16 representatives from Member States, and 11 from the civil society, including women’s health advocates and a representative from the Global Network of People Living with HIV, to present their own reading of the results and also to raise the issues that they face in their countries and in the context of their activities.

We paid special attention to invite people representing different positions. Last, but not least, we also have eight funding agencies and six implementing partners joining in the discussions. Overall, we are expecting almost 80 participants in Montreux. No need to say that we expect intense discussions that will touch upon many difficult issues.

Unaids.org: What do you expect as the outcomes of this meeting?

KD: The first and immediate outcome resides in the debate that is going to take place this week. This is the first time ever that such a wide range of stakeholders exchange views and discusses the consequences of male circumcision as an additional prevention method in the response to AIDS. At this stage, we cannot pre-empt the outcome. Maybe we will conclude the meeting with more questions than we began with- though I am hoping that at least some questions will be answered and that we will be able to make some recommendations.

The meeting will also identify what we need to do next in order to move forward. In any case, there will be a meeting report which we will make public shortly after the meeting.

Finally, I want to emphasize again and again that our objective is to examine male circumcision as an additional prevention method which should always be part of a comprehensive package which includes, among other elements, the correct and consistent use of male and female condoms, the delay in sexual debut and the reduction of sexual partners. The meeting will discuss how we can strengthen our communications so as not to undermine other prevention methods if we are to scale up male circumcision services.

If the United Nations moves forward with guidance to countries on male circumcision as a public health intervention for HIV prevention, it will be promoted as an ‘additional’ intervention to current HIV prevention packages; not as an alternative. People must understand that male circumcision does not provide complete prevention and they should be encouraged to use more than one of the prevention choices available to them.

Links:

Read the three part series on Male Circumcision:

Part 1 - Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture

Part 2 - Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now

Part 3 - Moving forwards: UN policy and action on male circumcision

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS releases 'Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention'

06 March 2007

06 March 2007 06 March 2007

Photo credit:UNAIDS/K.Hesse

UNAIDS has released Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention:Towards Universal Access to assist policy makers and planners in countries to strengthen their national HIV prevention response.

The development of the Guidelines recognises that universal access is not only about sustaining and increasing access to antiretroviral treatment for those in need, but also to ensure that all people, particularly those most vulnerable to HIV, are able to prevent HIV infection so as to bring about a decrease in the number of new HIV infections — estimated at 4.3 (3.6–6.6) million in 2006.

The Guidelines call on National AIDS Authorities – in the Spirit of the Three Ones Principles - to provide leadership in coordinating and strengthening their national HIV prevention efforts. To strengthen national efforts countries are being encouraged to ‘know your epidemic’ by identifying the behaviours and social conditions that are most associated with HIV transmission, that undermine the ability of those most vulnerable to HIV infection to access and use HIV information and services. Knowing your epidemic provides the basis for countries to ‘know your response’, by recognizing the organizations and communities that are, or could be, contributing to the response, and by critically assessing the extent to which the existing response is meeting the needs of those most vulnerable to HIV infection.

Photo credit:UNAIDS/G.Pirozzi

Dr Peter Piot, Executive Director of UNAIDS, said that, “We encourage countries to know their epidemic because we have learned over the last twenty-five years that the epidemic keeps evolving. It is important for countries to take stock of where, among whom and why new HIV infections are occurring. Understanding this enables countries to review, plan, match and prioritise their national responses to meet these needs”.

UNAIDS categorizes HIV epidemics scenarios as low level, concentrated or generalized. For planning purposes the Guidelines propose an additional scenario—the hyperendemic scenario. The hyperendemic scenariorefers to those areas, such as the high prevalence countries of southern Africa, where HIV is circulating in the general population through sexual networking – especially heterosexual multiple concurrent partner relations with low and inconsistent condom use -- and prevalence exceeds 15% in the adult population. Within countries and regions different scenarios may exist and the epidemic may evolve from one scenario to another depending on the response, the underlying dynamics and drivers of the epidemic.

To help countries prioritise their response, the Guidelines provide a synthesis of essential and proven prevention measures that countries can use to “tailor your prevention plans” in relation to the epidemic scenarios and to meet the needs of the populations with highest rates and highest risks of HIV.

Photo credit:UNAIDS/L.Gubb

Matching and prioritizing national response requires that countries set ambitious, realistic and measurable prevention targets in relation to their epidemic. This includes setting goals, and defining outcomes, outputs and processes for HIV prevention services to be delivered to the people and places where they are most needed. The Guidelines stress the need to constantly use strategic information, such as behavioural surveys, to measure and track whether they are achieving their objectives.

Dr Purnima Mane, Director, Policy, Evidence and Partnerships says that, “The fundamental intention underlying these guidelines is for countries to engage their leaders and communities to know their epidemics and to match the prevention response to meet their priority needs. Ensuring adequate coverage of most at risk and most vulnerable populations is essential to achieving Millennium Development Goal 6; and so too is urgent action to combat the drivers of the epidemic such as HIV related stigma, human rights violations, and gender inequality”.

The UNAIDS Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention: Towards Universal Access have been developed in consultation with the UNAIDS cosponsors, international collaborating partners, government, civil society leaders and other experts. They build on Intensifying HIV Prevention: UNAIDS Policy Position Paper and the UNAIDS Action Plan on Intensifying HIV Prevention.

Links:

Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention: Towards Universal Access (pdf, 3.87MB)

Intensifying HIV Prevention: UNAIDS Policy Position Paper (pdf, 3.80MB)

More information on Uniting for HIV Prevention

Feature Story

Moving forwards: UN policy and action on male circumcision (Part 3)

02 March 2007

02 March 2007 02 March 2007

In the final part of a special series on the issue of male circumcision and its links to the reduction of HIV acquisition, www.unaids.org discusses expected upcoming action and developments from the United Nations on male circumcision through a special interview with UNAIDS Chief Scientist, Dr Catherine Hankins

From 6-8 March 2007, public health experts from the World Health Organization, UNAIDS and other partner organizations will gather in Montreux, Switzerland, to discuss the topical and often thorny issue of male circumcision and its links to HIV prevention, and to define future United Nations guidance to countries on the policy and programming implications of recent research findings.

As the consultation approaches, UNAIDS’ Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Catherine Hankins gives a preview of the different issues that may be raised, and an insight into considerations for potential outcomes and action for the United Nations.

Unaids.org: Dr Hankins, you’ve been involved in the issue of male circumcision and its impact on HIV for many years—how do the current findings corroborate scientists’ claims that there is a link between circumcision and reduced HIV infections?

CH: For many years, researchers and scientists have noted that parts of Sub-Saharan Africa where circumcision is common, such as countries in West Africa, have much lower levels of HIV infection, while those in southern Africa, where circumcision is rare, have the highest. Before the availability of data from these three randomised controlled trials, multiple observational studies indicated that male circumcision carried with it a reduced risk of HIV infection. The latest findings from the three trials indicate that male circumcision provides a protective benefit against HIV infection of 50% to 60%

A further trial, led by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, to assess the impact of male circumcision on the risk of HIV transmission to female partners is currently under way in Uganda, with results expected in 2008.

Unaids.org: What is the United Nations doing about this latest evidence that male circumcision reduces risk of HIV acquisition?

CH: Although these results demonstrate that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the United Nations agencies involved in this work absolutely underline that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection- we need to make sure that men and women understand that circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners.

Next week, WHO, the UNAIDS Secretariat and their partners will review the trial findings in detail at a consultation which will define specific recommendations for expanding and/or promoting male circumcision. These recommendations will need to take into account a number of key issues including the cultural and human rights considerations associated with promoting male circumcision; the risk of complications from the procedure performed in various settings; the potential of male circumcision to undermine or to work in synergy with existing protective behaviours and prevention strategies that reduce the risk of HIV infection; and the financial and human resource implications of male circumcision in different service delivery settings.

In order to support countries or institutions that decide to scale up male circumcision services, with our partners we are developing technical guidance on ethical, rights-based, clinical and programmatic approaches to male circumcision. We are also developing guidance on training, standard setting and certification procedures.

Unaids.org: What are some of the key concerns about increasing male circumcision practice that will be discussed at the consultation?

CH: A number of thorny issues arise related to promoting male circumcision as a public health intervention for HIV prevention. Adult male circumcision has a higher risk of adverse effects than infant male circumcision, and should be undertaken by trained health workers in safe, adequately equipped and sanitary conditions with appropriate pre and post-surgical counselling and follow-up. There is a real need to ensure that male circumcision interventions for health benefits are differentiated from female genital mutilation which the UN opposes and is considered to have no health benefits and potentially severe consequences for women and girls.

We also have to take into account the cultural issues- within cultures and faith traditions in which male circumcision is not considered acceptable, promoting it may or may not prove challenging. Without question, we absolutely have to ensure that men and women are aware that male circumcision is not a ‘magic bullet’- it doesn’t provide total protection and it doesn’t mean people can stop taking the safe sex precautions they were already using, such as use of male or female condoms, delaying sexual debut, avoiding penetrative sex and decreasing the number of sexual partners. We must continue to promote combination prevention and ensure that male circumcision is perceived as an additional benefit but one that should be in combination with other strategies to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. We don’t want increased risk behaviour to offset the benefits.

If the United Nations moves forward with guidance to countries on male circumcision as a public health intervention for HIV prevention, it will be promoted as an ‘additional’ intervention to current HIV prevention packages; not an alternative.

Effective communication on male circumcision will be critical and will be an opportunity to reinforce messages on the need for a comprehensive approach to prevention that encourages people to use more than one of the prevention choices available to them.

Unaids.org: Would male circumcision be part of the HIV prevention response for all settings?

Countries with high HIV prevalence and low male circumcision levels may be among the first to consider the potential for male circumcision to play a role in their HIV prevention programming. Other countries may decide to provide male circumcision services to particular populations who could benefit from the additional protection that male circumcision can afford.

The UN and its partners are fully aware that male circumcision may raise cultural and religious issues – it should never be imposed and, if it is promoted, must be done in a culturally acceptable manner in settings where it is not traditionally practised.

Unaids.org: What are the risks of male circumcision?

CH: Like all types of surgery, circumcision is not without risk. Circumcision by unqualified individuals under unsanitary conditions with poorly maintained or sub-optional equipment can lead to serious, immediate and long-term complications, or even death. Where health professionals have been trained and equipped to perform safe male circumcisions, however, the rate of post-operative complications is less than 5% and the large majority of these resolve with simple, appropriate post-operative care.

Anecdotal accounts of serious complications, including penile amputation and death after male circumcision in traditional settings have been reported. It is difficult to give overall figures for adverse events in all settings, in part because well-documented studies of complication rates in low-and-middle income countries are rare.

Unaids.org: Is there a need to improve male circumcision practices?

CH: Absolutely. Action is required now to improve circumcision practices in many regions, and to ensure that health-care providers and the public have up-to-date information on the health risks and benefits of male circumcision. Many boys and men wishing to be circumcised do not have access to safe circumcision services nor to post-circumcision care if they do suffer from complications. Regardless of the HIV prevention benefits, it is now increasingly important to make existing practices safer. Where circumcision is legal, authorities need to ensure that practitioners are properly trained and licensed to do this procedure. Monitoring should also be done to ensure that procedures are performed safely and that untrained practitioners do not continue to perform unsafe circumcisions.

Unaids.org: Does male circumcision raise human rights issues?

CH: Yes, as is the case with all medical and health procedures. In line with internationally accepted ethical and human rights principles, UNAIDS and WHO are of the view that no surgical intervention should be performed on anyone if it results in adverse outcomes in terms of health or the integrity of the body, and where there is no expectation of health benefit. Nor should any surgical intervention be performed on anyone without informed consent, or the consent of the parents or guardians when a child is not capable of providing consent.

As male circumcision involves surgery and removal of a part of the body, it should only be performed under these conditions: a) participants are fully informed of the possible risks and benefits of the procedure; b) participants give their fully informed consent; and c) the procedure can be performed under fully hygienic conditions by adequately trained and well equipped practitioners with appropriate post-operative follow-up.

Unaids.org: What effect on the HIV epidemic might we expect if male circumcision were commonly practised where it currently is not?

An international group of experts have carried out a mathematical modelling exercise on the impact on HIV incidence of a programme of universal male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa, assuming the programme worked as it had in Orange Farm, South Africa and that all men would be circumcised within 10 years. The model predicts that 5.7 million infections and 3 million deaths would be prevented over 20 years among both men and women. There are many unknowns within this model but it does predict that male circumcision would provide a significant, potential benefit, similar to a partially effective vaccine. Importantly though, the model also shows that male circumcision alone cannot eliminate the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

Unaids.org: Could male circumcision eliminate the risk of HIV infection?

CH: No. Male circumcision alone certainly does not prevent men from becoming infected with HIV. Nor does it prevent women from being infected with HIV by men who have been circumcised. Circumcision needs to be seen as one of the range of methods to reduce the risk of HIV—including avoidance of penetrative sex, delaying sexual debut, reduction in the number of sexual partners, and correct and consistent male or female condom use. Male circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection during vaginal intercourse, but is unknown whether it would have an effect on other routes of sexual HIV transmission: the receptive partner in anal intercourse may not have a reduced risk due to the circumcision status of his or her partner and, if male, will not have a reduced risk due to his own circumcision status. It is also not known whether male circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection for the insertive partner during anal intercourse. Male circumcision has no effect in the case of HIV transmission through injecting drug use.

Unaids.org: Given all these considerations, is it likely the UN will recommending that adult men become circumcised as a way to protect themselves from HIV?

CH: This is what will be discussed at the consultation, and the partners expect to release information about the discussions and possible next steps at the end of the week’s meeting.

In any and all cases for future direction and action, the UN and its partners will certainly underline that male circumcision does not provide complete protection from HIV. It should therefore never replace other known effective preventive methods, such as delay in onset of sexual activity, abstinence from penetrative sex, correct and consistent use of condoms, and reductions in the number of sexual partners.

It’s very important that we stress that circumcised men, if HIV positive, can still infect their sexual partners if they do not use condoms during penetrative sexual intercourse.

Links:

Read Part 1 - Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture

Read Part 2 - Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now

Read more about the international experts meeting on male circumcision

Feature Story

Rock star’s legacy helps children living with HIV

01 March 2007

01 March 2007 01 March 2007

“He is clapping from wherever he is,” Maria Lucia Araujo said emotionally of what her son, Cazuza’s reaction would be to the children’s home “Viva Cazuza” which was founded in his name.

Cazuza, one of Brazil's best-known solo artists, died in 1990 of an AIDS-related illness in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 32. Today, 65 children living with HIV are being supported by Sociedade Viva Cazuza, a non-profit organization dedicated to helping children living with HIV which is funded by royalties from his songs.

In February 1989, Cazuza became the first Brazilian celebrity to announce publicly that he was HIV positive. In the October after his death, Maria Lucia Araujo founded the home for children living with HIV.

Lucia Araujo didn’t know anything about HIV or AIDS when she learnt of her son’s diagnosis. “When he first told me that he was HIV positive I assumed that he would recover within the year,” she said. Her son’s death transformed her life. Married to a wealthy husband she had no need to work, but she had to do something. “I would have gone mad,” she said. “I couldn’t have slept if I hadn’t done anything.”

So she opened the home, the first of its kind in Rio. Since its opening, the organization has helped 67 children. As the availability of antiretroviral drugs has improved so has the children’s health. “The children go to local schools and have an active life just like any of the other children in the area,” said Lucia Araujo.

UNAIDS estimates that globally there are around 2.3 million children under 15 years old infected with HIV and according to a recent report by UNICEF, some 15.2 million children under the age of 18 have lost one or both parents to AIDS.

“There is a real need to support children living with HIV in Brazil,” said Dr. Laurent Zessler, UNAIDS Country Coordinator in Brazil. “We must make sure these children are not discriminated against. Children living with HIV are able to stay in school and live full and active lives, HIV shouldn’t be allowed to take away their childhoods,” he added.

“Since my son died the nature of the virus has changed a great deal; it is no longer a gay man’s disease, now more and more women are affected. They often have no idea that they are HIV positive and pass it to their children without knowing,” Maria Lucia said.

Children come to the house through many different avenues. One of the 24 children currently living in the house is 15-year-old Danielle who arrived 10 years ago with her sister after her mother died and her father was unable to cope. During her stay she has built up a good relationship with her father and hopes to live with him again someday.

Paraguayan Jose was found at the age of three abandoned and very sick in a hospital on the Paraguayan border. Now, nine-year-old Jose wants to be a film director.

The organisation also supports young adults who have left the home. Once a week, the home’s clinic is open for HIV positive adults to collect their antiretroviral drugs. As with all Brazilians who are HIV positive, antiretroviral treatment is provided free of charge by the government.

Besides material support, Sociedade Viva Cazuza also operates a Web site where people can ask experts about AIDS issues. The experts receive around 12,000 questions a month. Maria Lucia is shocked by the questions still being asked 20 years after AIDS first arrived in Brazil. “The most common questions are still – how do I contract the disease? How can I protect myself from contracting the disease?” she said. “It is not like Cancer where the experts still are not sure what causes it or how to prevent it – to prevent AIDS it’s simple – use a condom.”

Maria Lucia has become a prominent spokesperson on AIDS appearing regularly on television. She believes her son’s heritage is not only ‘his beautiful songs’ but also the home, by being open about HIV and appearing in public as the illness progressed. “He did a lot to educate people and help reduce discrimination against people living with HIV,” she said.

All photo credit: J. Spaul

Links:

Sociedade Viva Cazuza Website

Cazuza's Website

Unite for children, unite against AIDS

Feature Story

Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now (Part 2)

28 February 2007

28 February 2007 28 February 2007In the second of a special three-part series on the issue of male circumcision and its links to the reduction of HIV acquisition, unaids.org considers current research findings.

It’s a subject that hits headlines, fuels discussions, sparks debate and causes some of the men in the room to wince and cross their legs. Male circumcision and its links to HIV is one of the most talked about issues within the AIDS response over the last years, with latest research findings driving potential change in the way male circumcision is practiced and implemented for the future in relation to HIV prevention.

In scientific circles, the perceived links between male circumcision and HIV infection are nothing new. For years, AIDS researchers have observed that many African tribes that circumcise boys or young men had lower HIV rates than those that do not, and that Africa's Islamic nations, where circumcision is near universal, had far fewer AIDS cases than predominantly Christian ones.

Now, trials in Kenya, Uganda and South Africa have all shown that male circumcision significantly reduces a man’s risk of acquiring HIV. The three sets of trials have shown circumcised men are up 50 to 60% less likely to acquire HIV during heterosexual intercourse.

Research findings

The first research proof came in 2005, when a study in South Africa, supported by the French agence nationale de recherches sur le sida (ANRS) and known as the 'Orange Farm Intervention Trial', was stopped early in the face of evidence that the men who had been randomly assigned to be circumcised were getting 60% fewer HIV infections than the men assigned to the control group.

In December 2006, on the recommendation of their Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), two similar studies in Uganda and Kenya were halted early by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) because the interim results showed a significant effect of male circumcision in preventing HIV acquisition in men.

The trial carried out in Kisumu, Kenya by researchers from the University of Nairobi, University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of Manitoba, and RTI International involving 2,784 men aged 18 to 24 showed a 53% reduction of HIV infections in circumcised men compared to uncircumcised men.

In Uganda, the trial, carried out in Rakai by researchers from Makerere University, the Uganda Virus Research Institute, Johns Hopkins University, and Columbia University New York, involved 4996 men aged 15 to 49 years old and showed that adult male circumcision reduced by 51% the risk of becoming infected with HIV.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the institute ended both trials early and offered circumcision to all men involved in them. The trials began in 2005 and were due to go until mid-2007.

The biology

Male circumcision involves the surgical removal of the foreskin, the tissue covering the head of the penis. Previous research shows that removing the foreskin is associated with a variety of health benefits including lower rates of urinary tract infections in male infants who are circumcised and reduced risk of certain inflammations and health problems associated with the foreskin.

Scientists say male circumcision probably reduces the risk of HIV infection because it removes tissue in the foreskin that is particularly vulnerable to the virus, and because the area under the foreskin is easily scratched or torn during sex. “Uncircumcised men may also be more vulnerable to sexually transmitted diseases, which in turn increase the risk of contracting HIV, because the region under the foreskin provides a moist, dark place in which germs can thrive,” said UNAIDS Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Catherine Hankins.

No ‘magic bullet’

The results of the trials in South Africa, Uganda and Kenya indicate that in certain settings, adult male circumcision could become an important addition to an HIV prevention strategy for men. “The trials indicate that male circumcision can lower both an individual's risk of infection and hopefully the rate of HIV spread through the community," NIH’s Dr Fauci said.

But experts— including the United Nations bodies working on the issue—caution that circumcision is no cure-all. Male circumcision does not provide complete protection against HIV infection; it only lessens the chances that a man will acquire the virus.

Circumcision is "not a magic bullet, but a potentially important intervention," said Dr. Kevin M. De Cock, director of the World Health Organization’s AIDS department.

“Men and women must understand that circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners,” said UNAIDS’ Dr Hankins

“ Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and abstaining from penetrative sex”, she said.

Safety, sanitation and communication

To ensure safe and clean operations, male circumcision should only be performed by well-trained practitioners in sanitary settings under conditions of informed consent, confidentiality, proper counseling and safety. “If male circumcision is to be promoted, this should be done in a culturally appropriate manner and people should be provided sufficient and correct information on HIV prevention to prevent them from developing a false sense of security and engaging in risky behavior,” said Dr Hankins.

These considerations and others in relation to the AIDS response, including the fact that male circumcision has the potential to be an expensive intervention, that more research is needed to address whether male circumcision reduces risk of transmitting HIV-particularly for female partners, and the different ethical and human rights issues raised by male circumcision, will form discussions of the United Nations consultation on male circumcision that will take place in Geneva from 5 March. Here, WHO, the UNAIDS Secretariat and their partners will review the detailed trial findings and will, if deemed appropriate, then define specific policy recommendations for expanding and/or promoting male circumcision.

“Male circumcision is a complicated issue which involves sometimes difficult discussion on issues of culture, tradition, religion, ethnicity, human rights and gender. The consultation will provide an excellent arena for moving the discussion and policy forward within the United Nations,” said Dr Hankins.

Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture (Part 1)

Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now (Part 2)

Moving forwards: UN policy and action on male circumcision (Part 3)

Related

Feature Story

Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture (Part 1)

26 February 2007

26 February 2007 26 February 2007With male circumcision and its links to HIV acquisition hitting the headlines and sparking debates around the world, in the first of a special three-part series on the issue, www.unaids.org takes a closer look at the historical, traditional and increasingly social reasons behind the practice of male circumcision across the world.

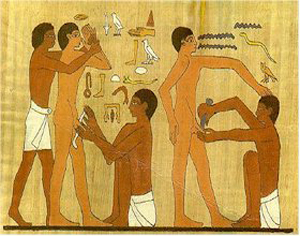

Male circumcision is one of the oldest and most common surgical procedures known, traditionally undertaken as a mark of cultural identity or religious importance.

Historically, male circumcision was practised among ancient Semitic people including Egyptians and those of Jewish faith, with the earliest records depicting circumcision on Egyptian temple and wall paintings dating from around 2300 BC.

With advances in surgery in the 19th century, and increased mobility in the 20th century, the procedure was introduced into some previously non-circumcising cultures for both health-related and social reasons.

According to current estimations, approximately 30% of all males across the world— representing a total of approximately 670 million men — are circumcised. Of this number, about 68% are of Islamic faith, less than 1% of Jewish faith, and 13% are non-Muslim, non-Jewish Americans.

“With the recent findings that male circumcision significantly reduces a man’s risk of acquiring HIV the practice is receiving renewed interest as the world looks to understand what this will mean for HIV prevention,” said UNAIDS Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Catherine Hankins. “Looking at the determinants of male circumcision, and the acceptability of male circumcision in non-circumcising societies give a better picture of how to take the latest research findings forward.”

Religious practice

In the Jewish religion, male infants are traditionally circumcised on their eighth day of life, providing there is no medical contraindication. The justification, in the Jewish holy book the Torah, is that a covenant was made between Abraham and God, the outward sign of which is circumcision for all Jewish males. The Torah states: “ This is my covenant, which ye shall keep, between me and you and thy seed after thee: every male among you shall be circumcised " (Genesis 17:10). Male circumcision continues to be almost universally practiced among Jewish people.

Islam is the largest religious group to practice male circumcision. As an Abrahamic faith, Islamic people practice circumcision as a confirmation of their relationship with God, and the practice is also known as ‘tahera’, meaning purification. With the global spread of Islam from the 7th century AD, male circumcision was widely adopted among previously non-circumcising peoples. There is no clearly prescribed age for circumcision in Islam, although the prophet Muhammad recommended it be carried out at an early age and reportedly circumcised his sons on the seventh day after birth. Many Muslims perform the rite on this day, although a Muslim may be circumcised at any age between birth and puberty.

The Coptic Christians in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians— two of the oldest surviving forms of Christianity— retain many of the features of early Christianity, including male circumcision. Circumcision is not prescribed in other forms of Christianity. In the New Testament, St. Paul wrote: "in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision count for anything" (Galatians 5:6) and a Papal Bull issued in 1442 by the Roman Catholic Church stated that male circumcision was unnecessary: “Therefore it strictly orders all who glory in the name of Christian, not to practise circumcision either before or after baptism, since whether or not they place their hope in it, it cannot possibly be observed without loss of eternal salvation,” it stated. Focus group discussions on male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa found no clear consensus on compatibility of male circumcision with Christian beliefs. Some Christian churches in South Africa oppose the practice, viewing it as a pagan ritual, while others, including the Nomiya church in Kenya, require circumcision for membership and participants in focus group discussions in Zambia and Malawi mentioned similar beliefs that Christians should practice circumcision since Jesus was circumcised and the Bible teaches the practice.

Ethnicity

Circumcision has been practiced for non-religious reasons for many thousands of years in sub-Saharan Africa, and in many ethnic groups around the world, including aboriginal Australasians, the Aztecs and Mayans in the Americas, inhabitants of the Philippines and Eastern Indonesia and of various Pacific Islands, including Fiji and the Polynesian islands.

In the majority of these cultures, circumcision is an integral part of a rite-of-passage to manhood, although originally it may have been a test of bravery and endurance. “Circumcision is also associated with factors such as masculinity, social cohesion with boys of the same age who become circumcised at the same time, self-identity and spirituality,” Dr Hankins explained.

The ethnographer Arnold Van Gennep in his 1909 work ‘The Rites of Passage’ , describes various initiation rites which are present in many circumcision rituals. These include a three stage process: separation from normal society; a period during which the neophyte undergoes transformation; and finally reintegration into society in a new social role.

“A psychological explanation for this process is that ambiguity in social roles creates tension, and a symbolic reclassification is necessary as individuals approach the transition from being defined as a child to being defined as an adult. This is supported by the fact that many rituals attach specific meaning to circumcision which justify its purpose within this context,” said Dr Hankins. For example, certain ethnic groups including the Dogon and Dowayo of West Africa, and the Xhosa of South Africa view the foreskin as the feminine element of the penis, the removal of which (along with passing certain tests) makes a man of the child.

Tradition plays a major part for many ethnic groups. Among ethnic groups of Bendel State in southern Nigeria, 43% of men stated that their motivation for circumcision was to maintain their tradition. In some settings where circumcision is the norm, there is discrimination against non-circumcised men. For the Lunda and Luvale tribes in Zambia, or the Bagisu in Uganda, it is unacceptable to remain uncircumcised, to the extent that forced circumcisions of older boys are not uncommon. Among the Xhosa in South Africa, men who have not been circumcised can suffer extreme forms of punishment, including bullying and beatings.

Circumcision as a social statement

Social reasons behind male circumcision are becoming ever more common. “The desire to conform is an important motivation for circumcision in places where the majority of boys are circumcised,” said Dr Hankins.

A survey in Denver, US where circumcision occurs shortly after birth, found that parents, especially fathers, of newborn boys cited social reasons as the main determinant for choosing circumcision (e.g. not wanting the son to ‘look different’ from the father).

In the Philippines, where circumcision is almost universal and typically occurs at age 10-14, a survey of boys found two-thirds of those surveyed choosing to be circumcised simply ‘to avoid being uncircumcised’, and 41% stating that it was ‘part of the tradition’. Social concerns were also the primary reason for circumcision in South Korea with 61% of respondents in one study believing they would be ridiculed by their peer group unless they were circumcised.

The desire to ‘belong’ is also likely to be the main factor behind the high rate of adult male circumcisions among immigrants to Israel from non-circumcising countries (predominantly the former Soviet Union).

In a number of countries, socio-economic factors also influence circumcision prevalence, especially in countries with more recent uptake of the practice such as English-speaking industrialised countries. When male circumcision was first practised in the United Kingdom in the late 19th and early 20th century, it was most prevalent among the upper classes. In the US, a review of 4.7 million newborn male circumcisions nationwide between 1988 and 2000 also found a significant association with private insurance and higher socioeconomic status.

Perceived health and sexual benefits

In more recent times, perceptions of improved hygiene and lower risk of infections through male circumcision have driven the spread of circumcision practices in the industrialised world.

In a study of US newborns in 1983, mothers cited hygiene as the most important determinant of choosing to circumcise their sons, and in Ghana, male circumcision is seen as cleansing the boy after birth. Improved hygiene was also cited by 23% of 110 boys circumcised in the Philippines and in South Korea, the principal reasons given for circumcision were ‘to improve penile hygiene’ (71% and 78% respectively) and to prevent conditions such as penile cancer, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. In Nyanza Province, Kenya, 96% of uncircumcised men and 97% of women irrespective of their preference for male circumcision stated their opinion that it was easier for circumcised men to maintain cleanliness.

Perceived improvement of sexual attraction and performance can also motivate circumcision. In a survey of boys in the Philippines, 11% stated that a determinant of becoming circumcised was that women like to have sexual intercourse with a circumcised man, and 18% of men in the study in South Korea stated that circumcision could enhance sexual pleasure. In Nyanza Province, Kenya, 55% of uncircumcised men believed that women enjoyed sex more with circumcised men. Similarly, the majority of women believe that women enjoyed sex more with circumcised men, even though it is likely that most women in Nyanza have never experienced sexual relations with a circumcised man. In northwest Tanzania, younger men associated circumcision with enhanced sexual pleasure for both men and women, and in Westonaria district, South Africa, about half of men said that women preferred circumcised partners.

Expected increase in demand

Global estimates in 2006 suggest that about 30% of males — representing a total of approximately 670 million men — are circumcised.

With latest research findings suggesting that circumcised men have a significantly lower risk of becoming infected with HIV, demand for safe, affordable, male circumcision is expected to increase rapidly.

“Since male circumcision is now shown to be effective in reducing the risk of HIV acquisition, care must be taken to ensure that men and women understand that the procedure does not provide complete protection against HIV infection,” said Dr Hankins, underlining that these issues will be discussed at the “ Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention Research - Policy and Programme Implications” International Consultation to be held in Montreux from 6-8 March 2007. “Male circumcision must be considered as just one element of a comprehensive HIV prevention package that includes the correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reductions in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations and abstaining from penetrative sex. Just as combination treatment is the best strategy to treat HIV, combination prevention is the best strategy to avoid acquiring or transmitting HIV”, she added.

“Action is also required to improve the safety of circumcision practices in many countries and to ensure that health care providers and the public have up-to-date information on the health risks and benefits of male circumcision,” she said.

Links:

Read Part 2 - Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now

Read Part 3 - Moving forward: UN policy and action on male circumcision

Related

Feature Story

Male circumcision and HIV: a web special series

23 February 2007

23 February 2007 23 February 2007

Male circumcision is one of the world’s oldest surgical practices; carvings depicting circumcisions have been found in ancient Egyptian temples dating as far back as 2300 BC.

In recent months, the issue of male circumcision and its links to the transmission of HIV has hit the headlines and sparked debates across the world. Trials in Kenya, Uganda and South Africa have now all shown that male circumcision significantly reduces a man’s risk of acquiring HIV.

As UNAIDS, the World Health Organization and other partners prepare to look at how to take these findings forward, in terms of UN guidance to countries on policy and programming, at a consultation to be held in Geneva from 5-8 March 2007, www.unaids.org takes an in-depth look at the issue of male circumcision in a special three-part series. Where did male circumcision originate, who practices it and why? These questions and others relating to the history and determinants of male circumcision will be considered in part one of the series – ‘Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture’, published on Monday 26 February. On Wednesday 28 February, part two –‘Male circumcision and HIV: The here and now’ will summarize current research findings on male circumcision and HIV acquisition. Part three, to be published on Friday 2 March will discuss future action and developments from the United Nations and feature a special interview with UNAIDS Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Catherine Hankins.

Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture (Part 1)

Male Circumcision and HIV: the here and now (Part 2)

Moving forwards: UN policy and action on male circumcision (Part 3)

Related

Feature Story

HIV and refugees

23 February 2007

23 February 2007 23 February 2007

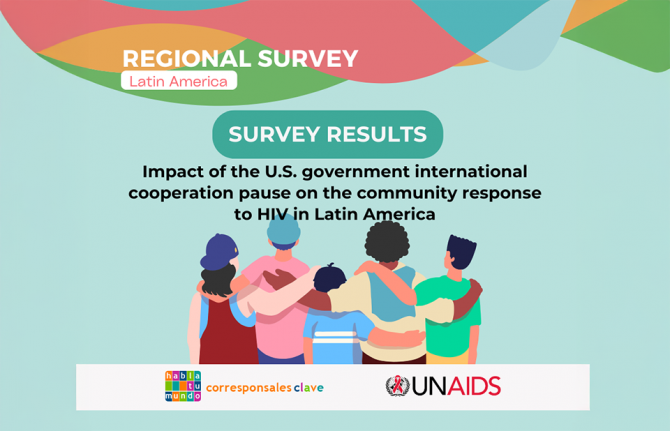

According to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, "A refugee is a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country". Conflict,

persecution and violence affect millions of people worldwide, forcing them to uproot their lives and seek refuge in a different country.

At the end of 2005, there were 8.4 million refugees worldwide. Of these, approximately 30% were in sub-Saharan Africa, 29% in Central and South-West Asia, North Africa and the Middle East and 23% in Europe.

Displacement of people from their country of origin has an enormous effect on their lives, as well as upon the lives of host communities.

Conflict and displacement make women and children highly vulnerable to the risk of HIV. As refugees struggle to meet their basic needs such as food, water and shelter, women and girls are often forced to exchange sexual services for money, food or protection.

“Women and girls are often disproportionately affected by displacement. They need special attention in terms of HIV including protection from violence and exploitation,” said Dr. Purnima Mane, Director of Policy, Evidence and Partnerships at UNAIDS.

Among other problems, refugees often do not have access to HIV prevention commodities and programmes. Access to basic HIV-related care and support is also rarely given adequate attention. Despite improvements in the availability of antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries, very few refugees have access to it.

“We advocate for refugees to access HIV services in the same manner as that of the local population. Some countries in Southern Africa provide both refugees and the host population free antiretroviral drugs using Government services,” said Dr. Paul Spiegel, Head of HIV Unit, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Many host countries are already overburdened by the impact of HIV, and are often unable or unwilling to provide the HIV-related services refugees need and to which they have a right under international refugee and human rights law.

In order to reduce the risk of HIV infection and improve access to HIV-related prevention, treatment, care and support of refugees, UNAIDS in collaboration with one of its Cosponsors, UNHCR, has developed a new policy brief that focuses specifically on actions required to prevent HIV and mitigate the effect of HIV on refugees and their host communities.

The policy brief focuses on emergency and post-emergency phases and suggests actions for governments, civil society and international partners in order to ensure that refugee and human rights laws are applied, and that the needs of refugees are included into national HIV policies and programmes.

All photo credit: UNAIDS