Feature Story

Maximizing the potential of a new HIV prevention method: PrEP

01 November 2016

01 November 2016 01 November 2016Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—most often a combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine taken orally as a daily tablet—is extremely effective at preventing HIV infection when taken regularly.

The choice of PrEP is recommended for people who are HIV-negative but at high risk of becoming infected. The people who can benefit most from PrEP—including gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, serodiscordant couples before the partner living with HIV becomes virally suppressed and young women and girls in the areas of sub-Saharan Africa most affected by HIV—are located where there are high rates of untreated HIV and inconsistent condom use.

People starting on PrEP must be HIV-negative and undergo repeat HIV testing every three months. The side-effects of taking PrEP are usually mild and short-lived. The risk of developing resistance to PrEP medicines is extremely low, as long as the person is confirmed to be HIV-negative when starting PrEP.

In the past two years, PrEP roll-out has moved quickly. It is estimated that in October 2016 around 100 000 people were using PrEP in more than 30 countries, with the majority of users in the United States of America. The UNAIDS target is for there to be 3 million people on PrEP worldwide by 2020.

There are now active national PrEP programmes in Australia, France, Kenya, Norway, South Africa and the United States. Botswana is pursuing regulatory approval and creating an implementation plan, while Thailand and Zimbabwe are among other countries producing guidelines for PrEP roll-out. In addition, more than 20 projects around the world are exploring the use of PrEP.

However, even where there is an existing national programme, PrEP uptake is unequal and the people who would benefit most do not always gain access. Many activists in the AIDS response continue to criticize this inequality. “PrEP is powerful, it has to reach the disempowered,” said Nöel Gordon of the Human Rights Campaign.

PrEP adds to the package of proven prevention options already available. PrEP should be used in conjunction with other prevention methods, such as male and female condoms, voluntary medical male circumcision and antiretroviral therapy for all people living with HIV. When antiretroviral therapy is effective in a person living with HIV, the virus becomes undetectable in the person’s blood and the risk of transmitting the virus to a partner approaches zero. No single HIV prevention method is 100% protective and PrEP does not prevent other sexually transmitted infections or prevent unintended pregnancy. Condoms remain the most widely available and affordable HIV prevention tool and as such should always be promoted along with PrEP.

The benefits of choosing PrEP can be psychological as well as physical and the use of PrEP may counter the anxiety and isolation felt by some people who feel they lack the ability to control their risk of exposure to HIV. PrEP can give people more autonomy about their sexual decision-making, which may also include risk reduction. PrEP may promote improved communication and intimacy with a partner, reduced fear of intimate partner violence, raised self-esteem and greater engagement with all aspects of sexual health.

Offering PrEP can encourage more people at the highest risk of HIV to attend HIV clinics, undergo HIV testing and access either PrEP or treatment depending on the test result. Either way, the outcome is good for the individual and good for HIV prevention.

PrEP gives us one more tool that we can use to better tailor the prevention package to each person’s individual needs, which can change over time. PrEP is not for everyone and is not for ever. Routine PrEP follow-up involves regular review of broader sexual health, including the diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections and discussion of appropriate combination HIV prevention strategies and contraception, as appropriate.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Feature Story

PrEP in South Africa

04 November 2016

04 November 2016 04 November 2016There is strong demand for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) from many people at high risk of HIV infection, but in many areas it is not yet available. Where PrEP is not available through well-structured programmes, people may seek to obtain it through unofficial channels. Self-prescribing PrEP in this way would result in inadequate follow-up with no linkage to health service support and an increased risk of using substandard products, drug resistance and reduced impact.

South Africa has taken on these challenges and was the first country in Africa to approve the use of antiretroviral medicines for prevention. The country has accessed a generic supply of PrEP, thereby reducing the price of the medicines, and its delivery is integrated with other services.

The South African PrEP model is based on both rights and needs, and is initially intended for sex workers, who have the highest HIV prevalence in South Africa and face high levels of stigma and discrimination. User-friendly services have been designed in partnership with sex workers; however, the decision to use PrEP remains an individual choice, free from coercion.

Adding PrEP to combination prevention services is affordable, despite the costs associated with its roll-out, since those costs are expected to be offset by the savings made from avoiding new HIV infections and the associated benefits of increased contact with sexual health services by people at high risk of HIV infection.

“People ask me “How can you afford to implement new interventions?” and I always reply, “How can we afford not to?” Once you answer this question, you will find the way to work it out,” says Aaron Motsoaledi, South Africa’s Minister of Health.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Region/country

Feature Story

Countries in Asia start to roll out PrEP

02 November 2016

02 November 2016 02 November 2016The Thai Red Cross Anonymous Clinic (TRCAC) sits back from a busy street in Bangkok, Thailand. It’s a familiar place for Jonas Bagas, who visits the leafy compound regularly because he is taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as part of a project being piloted by the clinic.

PrEP is the use of antiretroviral medicine in the form of a daily pill to prevent people from acquiring HIV. It is demonstrated to be highly effective in preventing the transmission of HIV among people at high risk of becoming infected.

“One reason I started was because I had a sexual partner who was HIV-positive,” explains Mr Bagas, who is from the Philippines but living in Bangkok for his job with APCASO.

TRCAC started its PrEP project at the end of 2014. Users are charged US$ 1 a day for their supply of pills, along with the recommended counselling and health evaluations. PrEP is only for people who are HIV-negative, so users undergo an initial HIV test and a check for other sexually transmitted infections as well as tests to measure how the liver and kidneys are functioning. After the first month, users repeat the evaluation and then return for testing every three months.

The most common side-effects of PrEP are nausea, headache and weight loss in the first month, but no serious toxicity has been observed during trials. “I find a huge urge to sleep right after taking PrEP, but since I take it at night, that’s not a huge minus,” said Mr Bagas.

While adherence and regular HIV testing present challenges for scaling up PrEP use, researchers describe it is a breakthrough in HIV prevention. Consistent condom use remains low in Asia. In most major cities less than half of gay men and other men who have sex with men are using condoms consistently, which is too low to have an impact on stopping the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS and the World Health Organization recommend PrEP as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV exposure and who are ready to have regular HIV testing.

“We have been waiting quite a long time to get an HIV prevention method that you can use in privacy and without anxiety. PrEP is the answer to that,” said Nittaya Phanuphak, Head of the Prevention Department at the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre.

PrEP does not prevent other sexually transmitted infections and is not a contraceptive, so health experts say it is best integrated with other sexual and reproductive health services, including the supply of condoms.

Surveys of potential users in Asia find that there is still a low awareness of PrEP as a prevention method. “I hope that PrEP becomes available in the Philippines soon,” said Mr Bagas.

In fact, the nongovernmental organization LoveYourself is starting a pilot project for PrEP, including regular check-ups, risk reduction and adherence counselling, in two of its clinics in Manila, Philippines, in November. “We will embed PrEP education in the HIV testing process. So all those who are going through HIV testing in our clinics, which is about 60 to 100 people a day, will be given PrEP information,” says Chris Lagman, the Director of Learning and Development at LoveYourself.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Region/country

Related

Update

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

31 October 2016

31 October 2016 31 October 2016Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the latest addition to efforts to expand combination prevention options for people at high risk of HIV infection. The number and scope of PrEP activities is increasing globally, while the scale and coverage outside the United States of America remain limited. In October 2016 an estimated 100 000 people were enrolled on PrEP, the majority of whom were in the United States. A significant but unquantifiable number of people are accessing PrEP through less regulated means, for example via the internet. The rapid establishment of government-regulated programmes will improve the monitoring and evaluation of PrEP’s use and its impact on the epidemic. Considerable additional effort will be needed to attain the new global target of reaching three million people at substantial risk of HIV infection with PrEP by 2020.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Feature Story

Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV

24 October 2016

24 October 2016 24 October 2016Over the past five years, there has been a rapid scale-up of services to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. This has reduced the annual number of new infections among children by 50% worldwide since 2010. Globally, an estimated 77% of pregnant or breastfeeding women living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral medicines to prevent transmission of HIV to their children in 2015, up from 50% in 2010.

Antiretroviral medicines have averted 1.6 million new infections among children since 2000. There has also been a dramatic reduction in AIDS-related paediatric deaths. In the 21 priority countries that were the focus of the Global Plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children and keeping their mothers alive (Global Plan), AIDS-related mortality among children under 15 years of age dropped by 53% between 2009 and 2015. In countries such as Botswana, Burundi, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland, even greater reductions, above 65%, were achieved.

However, this welcome news is tempered by some complex remaining challenges. In 2015, there were 1.8 million children under 15 years of age living with HIV worldwide. An additional 150 000 children acquired HIV globally in 2015 (2800 a week), and 110 000 children died of AIDS-related causes (300 a day). In some high-burden countries, such as Angola, Chad and Nigeria, less than half the pregnant or breastfeeding women living with HIV are receiving antiretroviral medicines.

Programmes to help women avoid HIV infection remain underdeveloped and fragile, leading to 900 000 new HIV infections among women over the age of 15 years in 2015. They joined the 17.8 million women already living with HIV, and when they decide to have children they will need services to prevent transmission to their children and maintain their own health. Programmes to help women living with HIV avoid unintended pregnancies also remain inadequate: a recent study in Kenya found that despite improvements in coverage of family planning, women living with HIV were more likely to have experienced an unintended pregnancy than other women.

The World Health Organization (WHO) now recommends treating everyone living with HIV, but it is also essential to maintain good adherence to antiretroviral medicines in order to ensure their efficacy. Good adherence suppresses viral load to undetectable levels, greatly reducing onward transmission to the baby while restoring the mother’s immune system for better health. However, many women gradually stop taking the medicines after the baby is born, increasing the risk of transmission during breastfeeding and placing their own health in jeopardy. In Malawi, a study showed that a third of 7500 pregnant or breastfeeding women did not adhere to antiretroviral therapy adequately, compromising the benefits of treatment and increasing their risk of developing drug resistance.

Access to diagnosis and treatment among children has improved, but much remains to be done. Among the 21 Global Plan priority countries, only half the children exposed to HIV received virological testing within two months of birth, as recommended by WHO. Since mortality among untreated infants is highest in the first three months of life, prompt diagnosis and linkage to treatment are crucial. Yet only half the children under 15 living with HIV in those countries were accessing treatment, compared to 80% of pregnant women living with the infection. This signals service delivery failure for children.

In order to address the unfinished agenda of the Global Plan, UNAIDS and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief have launched a follow-up initiative known as Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free. With the goal of ending paediatric AIDS, this framework embraces the aspiration that every child should be born and remain HIV-free (start free), every adolescent and young woman should be able to protect themselves from HIV (stay free) and every child and adolescent living with HIV should have access to quality HIV treatment, care and support (AIDS-free).

Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free includes the targets endorsed in the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS of 95% of pregnant and breastfeeding women accessing antiretroviral medicines, reducing new HIV infections among children to 40 000 and 1.8 million children living with HIV accessing HIV treatment by 2018. It also aims to reduce new HIV infections among adolescents to under 100 000 and for 1.5 million adolescents to be on HIV treatment by 2020.

Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free promotes concerted and coordinated country-led action designed to close the remaining HIV prevention and treatment gap for children, adolescent women and expectant mothers. Its success will depend on tailor-made acceleration and implementation plans to respond to the country context, building on successful strategies to strengthen systems where necessary and identifying critical opportunities and actions to expand access to life-saving HIV treatment and prevention services. To support implementation, the framework also calls on industry, civil society and international partners to focus on investing in efficient and cost-effective solutions that maximize programme outcomes.

Like the Global Plan, Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free places women living with HIV at the centre of the response.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Feature Story

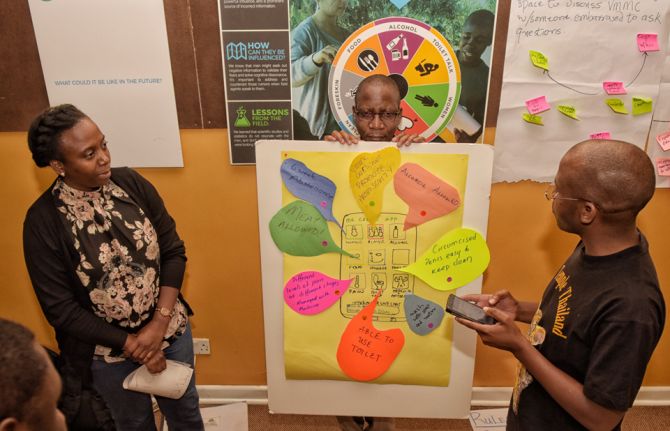

Using market research for long-term sustainability of VMMC in Zimbabwe and Zambia

19 October 2016

19 October 2016 19 October 2016Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) provides at least a 60% protective effect against HIV infection for men, but, while service delivery for VMMC has improved, uptake has stalled. In response, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded Ipsos Healthcare, a market research company, to investigate how to better understand behavioural and psychographic characteristics of men and boys and the barriers and facilitators within their journey from awareness of the VMMC to uptake.

Much is known about why men undergo VMMC, but those reasons and how men’s beliefs influence decisions to opt for it have not been systematically mapped.

The stages a man goes through when deciding to have VMMC in Zambia and Zimbabwe were documented in order to understand the path to the decision, what affected their decision, the roles of key influencers and how boys and men tend to take different paths to VMMC, depending on their age. Ipsos discovered that, on average, it took men two years and three months to move from awareness of VMMC to having the procedure.

Ipsos surveyed 2000 men between the ages of 15 and 30 in the two countries. The findings showed that men fall into six groups with respect to their attitudes towards VMMC and wanted answers regarding five themes: sex appeal; procedure; pain; social support; and the benefits.

With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to translate this research to practice, PSI Zimbabwe and the Society for Family Health, Zambia, used the results of the research to fine-tune and tailor messages to different groups of men. The research also improved the confidence of community workers in delivering previously uncomfortable messages, especially on pain and sex.

PSI Zimbabwe and the Society for Family Health, Zambia, prioritized the different groups by group size, ease of conversion, ability to advocate with peers and risk behaviour. After analysis of the research, they created “personas” of each group and identified areas where programmes and specific messaging could have the most impact.

Community workers mobilizing demand for VMMC report that they are able to quickly identify potential clients from the prioritized groups and target age groups. They are seeing fewer men but achieving a higher conversion rate as a result of the shift from group discussions to one-on-one discussions based on the research.

PSI Zimbabwe and the Society for Family Health, Zambia are now piloting messages and final concepts before scaling up programmes for the long-term sustainability of VMMC implementation.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Feature Story

Thailand is the first country in Asia to achieve elimination of HIV transmission and syphilis from mothers to their children

27 October 2016

27 October 2016 27 October 2016Sixteen years ago, Anya Nopalit was thrilled to learn that she was pregnant, but then she received devastating news. “I learned that I had HIV. I was really sad and disappointed. I wondered, why did this happen to me?” said Ms Nopalit, who lives in a fishing village in Chantaburi province in south-east Thailand.

Her doctor encouraged her to have an abortion, but she was determined to keep her baby. “I thought what will be, will be,” said Ms Nopalit.

Luckily, in the very same year that Ms Nopalit learned about her diagnosis, Thailand became one of the first countries in the world in which pregnant women living with HIV had access to free antiretroviral therapy. Untreated, women living with HIV have up to a 45% chance of transmitting the virus to their children during pregnancy, delivery or breastfeeding. However, the risk drops dramatically if HIV treatment is given to both mother and child.

Ms Nopalit followed the treatment regimen advised by her doctor and her son was born HIV-free.

“I was so happy when the doctor told me he was HIV-negative,” said Ms Nopalit.

Thailand’s early commitment to stop babies from being born with HIV has saved many lives and in June 2016 the country received validation from the World Health Organization (WHO) for having eliminated not only the transmission of HIV but also of syphilis from mothers to their children.

According to Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health, the number of children who became infected with HIV in 2015 was 86, a decline of more than 90% over the past 15 years. The rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Thailand declined from 13.6% in 2003 to 1.1% in 2015. The WHO global guideline considers mother-to-child transmission of HIV to be effectively eliminated when the rate of transmission falls below 2%.

At the Tha Mai Hospital in Chantaburi province, where Ms Nopalit accesses her HIV treatment, paediatric HIV cases have become uncommon.

“For the last three years, there were no new cases of mother-to-child transmission,” said Monthip Ajmak, Senior Nurse, Antenatal Care, Tha Mai Hospital.

One of the factors behind Thailand’s remarkable achievement is a well-developed national health system that provides quality services in even the most remote areas. According to Thai health authorities, nearly all pregnant women are routinely screened for HIV and if they are found to be HIV-positive the women start lifelong antiretroviral therapy. More than 95% of pregnant women diagnosed with syphilis also receive treatment.

In Thailand, health-care services for mothers living with HIV are fully integrated into maternal and child health-care programmes in hospitals and are covered by Thailand’s universal health-care coverage.

“Public sector staff receive continuous training, from basic counselling skills to providing a treatment regimen,” said Danai Teewanda, Deputy Director-General, Department of Health, Thailand Ministry of Public Health.

Community leadership has ensured that mothers living with HIV are linked to hospitals and supported throughout their pregnancy. The Best Friends Club at the Thai Mai Hospital has 160 members, who include men and women living with HIV. The club is divided into three groups, with more recent members meeting every month and long-time members meeting twice a month.

“Our club provides counselling services at the antenatal clinic. We coordinate with the hospital staff and provide information to women on how to take care of themselves,” said Malinee Vejchasuk, a counsellor with the Best Friends Club.

Ms Nopalit and her husband wanted to have another child. Four years ago, she gave birth to her second son.

“I am so happy that my two children are healthy and HIV-free. They are lively and play like their friends,” said Ms Nopalit.

When he is not in school, her eldest son now accompanies his parents when they catch crabs, which is their family business, while their youngest son runs around the beach and builds sand castles.

Video: Thailand is first country in Asia to eliminate mother-to-child HIV transmission

Thailand has received validation for having eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, becoming the first country in Asia and the Pacific region and also the first with a large HIV epidemic to ensure an AIDS-free generation. Meet Anya Nopalit, a mother living with HIV who has two HIV-negative children.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Tireless Indian doctor dedicated to women’s health

28 October 2016

28 October 2016 28 October 2016Gita and her husband arrived at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy (Sir J.J.) Hospital more than 15 years ago desperately wanting to have children. Because they were living with HIV, doctors had discouraged them from becoming parents, so they travelled five hours to bustling Mumbai, India, to see Rekha Daver, with the hope of finding a solution. Any solution.

Ms Daver is a doctor who heads the gynaecology department at the state-run hospital. Under her leadership, the hospital has become a referral centre for HIV-positive pregnant women, who are often turned away from other health facilities.

“Back then I could not guarantee that their child would not be HIV-positive, but I enrolled Gita on our antiretroviral therapy programme,” Ms Daver recalled. Subsequently, Gita’s husband was enrolled on the programme. Within a year Gita gave birth to a baby girl at the hospital.

“They never missed an appointment and when their daughter was born HIV-negative you should have seen their happiness,” she said. The couple, with their teenager in tow, still visit Ms Daver, which delights her. “It is not just a question of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV, it’s also having two adults living healthy lives.”

Ms Daver knows all about giving life. Since 2000 her team has performed more than 1 000 deliveries of HIV positive women. As of late there is cause to celebrate because in the last two years 100 women on the new three-drug regimen have had children born HIV-free.

Sarita Jadav, the New Delhi United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Focal Point for HIV and School Health Education, praised Ms Daver. “Maternal and child health is one of her passions and she has dedicated more than 37 years to servicing underprivileged women,” she said. Ms Jadav stressed the fact that despite having studied and worked in the United States of America and obtained a green card, Ms Daver chose to return to India and work in state hospitals and to train thousands of medical students.

“Her tireless efforts to bring about change and to save lives have been admired by all,” Ms Jadav added.

Ms Daver talked about the importance of counselling. “When I see women who are HIV-positive and their husbands HIV-negative there are often societal pressures on the couple, not so when the man is HIV-positive and the woman is negative,” she said. “My team and I have been trying to raise awareness about safe sex practices and family planning.” She credits her work at the Human Reproduction Research Centre and at the Indian Council of Medical Research in broadening her scope regarding women’s health.

Supporting women has driven Ms Daver’s career. She always knew she wanted to be a doctor and had set her sights on being a surgeon, but growing up in a small town she realized that helping women was key and that she could make a bigger impact as an obstetrician/gynaecologist.

After attending medical college in India, she spent three years at the Texas Medical Center in Houston, United States. When she decided to move back to India her husband Dr Gustad (medical school sweetheart) and two children moved back with her.

In 1990, she started at the Sir J.J. Hospital and it was then that she started to see more and more women living with HIV.

“I realized there was no cure and that perhaps my best bet was to focus on prevention, especially from mother-to-child.”

After studying programmes in Thailand and Uganda, Ms Daver’s team started providing access to antiretroviral medicine to mothers living with HIV during their pregnancy. Without antiretroviral medicine, between 33% and 45% of infants born to women living with HIV will become infected with HIV. The Sir J.J. Hospital project became a pilot programme and Ms Daver trained other doctors from across India.

With the success of programmes to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, Ms Daver can once again promote breastfeeding. “Before I worried so much because I was saving the child but mortality rates remained high because of a lack of antibodies,” she said. “Now women can safely breastfeed, which makes me so happy,” she said.

Her enthusiasm for her work is infectious, explains her daughter. “I always saw my mother’s devotion to people living with HIV, as well as her passion regarding women’s issues,” said the New York based Roshni Daver. “In fact she inspired me to become a doctor.”

“The key to my mother’s long and successful career is her excellent time management, or perhaps it’s because she wakes up very early,” said her daughter.

Her mother sees it another way, saying, “It gives me a great sense of satisfaction to help all these underprivileged women as well as to train the future generation of doctors.”

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Lives changed on the way to zero

26 October 2016

26 October 2016 26 October 2016It never crossed Khonjiswa Mdyeshana’s mind that she could be HIV-positive. So, in 2006, when she tested positive for HIV while pregnant with her first child, she couldn’t believe it. She insisted on taking the test three times. Much to her shock, every result came back positive. “In my mind, it was the end of the world for me and my child,” she says.

What Ms Mdyeshana didn’t know was that working alongside the doctors and nurses at her health clinic were HIV-positive Mentor Mothers, employed and trained by Africa-based nongovernmental organization mothers2mothers (m2m). The Mentor Mothers provided women just like her with education and support to initiate and adhere to their HIV treatment.

“The women at m2m made me feel welcome and unafraid. They told me their own stories of living with HIV. They taught me how to prevent spreading the virus to my baby and live positively. I have to be honest, I was not 100% sure about everything, but somehow I had new hope that it was not the end,” Ms Mdyeshana says.

Since m2m was founded in 2001, it has become a global leader in efforts to bring paediatric HIV infections to zero and improve the health and well-being of mothers, families and communities.

The m2m Mentor Mother model has been proven to reduce the number of infants who become infected with HIV and improve the health outcomes of mothers and babies, while also saving money in averted HIV treatment costs. A recently released annual evaluation of m2m’s programmes found that, in 2015, m2m achieved significant results:

- m2m virtually eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV among its clients for the second year in a row, with a mother-to-child transmission of HIV rate of 2.1% after 24 months.

- In South Africa, m2m’s transmission rate was even lower—1.1% after 18 months.

- Mothers who met two or more times with a Mentor Mother were more than seven times more likely to have their babies tested for HIV at six weeks compared to mothers who had met a mentor just once.

“It’s a joy to go into a site and hear a nurse or the head of the clinic say, “You need to know that it’s been three years since we have had a baby born in this clinic with HIV because of mothers2mothers,”” says m2m President and Chief Executive Officer, Frank Beadle de Palomo.

However, children are still becoming infected during the breastfeeding period. And there is a rising number of infections and deaths among adolescents, particularly adolescent girls and young women.

Responding to this need, m2m now engages mothers and their families over a longer period of time with a family-centred approach. m2m looks beyond survival, focusing on giving children the opportunity to thrive through its early childhood development and paediatric case finding and support programmes. And the new DREAMS initiative in South Africa is providing adolescents with the skills and knowledge necessary to protect themselves and the next generation from HIV.

As for Ms Mdyeshana, she has come a long way since 2006. She now works as a Mentor Mother, helping other women realize that living with HIV is not the end of their world. She is a proud mother to two HIV-free children, who are full of life, happiness and big dreams.

Her oldest, Luthando, now nine years old, tells his mother he is studying hard so that when he grows up he can get a good job and buy them a bigger house. That job? He says he is going to become a doctor, because he sees “a lot of sick people around” and wants to help them. While he works towards that dream, he is practising his medical skills at home, reminding his mother, who he describes as “strong and beautiful,” to take her HIV medicine every day.

Hands up for #HIVprevention — World AIDS Day campaign

Update

Closing the diagnostics gap for HIV for young infants

25 October 2016

25 October 2016 25 October 2016To achieve the Fast-Track Targets and end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, new HIV infections among children must be eliminated. HIV can pass from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, but with antiretroviral therapy mother-to-child transmission rates can fall to 5% or less.

The World Health Organization (WHO) promotes a comprehensive approach to preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. One important part of this strategy is to provide appropriate treatment, care and support to mothers living with HIV, their children and other family members.

Since 2005, owing to effective programmes that prevent mother-to-child transmission, the number of children born HIV-positive has dropped by about 70%. In 2015, around 1.4 million mothers living with HIV gave birth and 150 000 infants were infected with HIV globally. HIV-positive infants have their highest mortality in the first three months of life, so their HIV status must be diagnosed quickly in order that they can receive the treatment they need.

However, a serious diagnostics gap exists. Only 51% of infants exposed to HIV globally are tested by the time they are six weeks old, the age recommended by WHO. Half will never receive their results. Of those who do test positive and receive their results, only half are linked to care. So of the 150 000 babies born HIV-positive in 2015, only around half will be linked to care.

UNITAID is helping to close the diagnostics gap. Through its partners, UNITAID has invested more than US$ 300 million to widen availability to affordable, quality-assured diagnostic technologies in low- and middle-income countries. Crucially, UNITAID is making those tests available where people seek care, even in remote settings, to ensure that young patients quickly get the treatment they need.

Early infant diagnosis (EID) tests are suitable for infants, whereas rapid diagnostic tests are unsuitable for young infants, as a mother’s antibodies can be present in her child’s blood for up to 18 months after birth. UNITAID aims to make EID tests available for less than US$ 30. The test takes less than two hours to run, so infants can get same-day diagnosis and be linked immediately to care. This reduces the number of infants whose results are lost or delayed, and saves on the costs of later diagnosis.

With additional refinements, point-of-care testing of infants could further decrease infant mortality. UNITAID Operations Director Robert Matiru stresses the importance of regular testing. “Testing at birth can tell physicians if a baby was infected in utero,” he says. “But if a child is infected at birth, HIV seroconversion will not be detectable in the blood until weeks later. Re-testing at the recommended 6 weeks is essential.”

UNITAID currently has projects under way to make point-of-care EID and viral load tests available and affordable in 16 African countries. Innovative platforms, tailored to decentralized health settings, make it easy for health workers to carry out several types of tests. UNITAID funds operational research to check that each health solution is cost-effective, appropriate to the setting and scalable. The insights gained from this work in turn inform treatment guidelines, national plans and policies for preventing and treating HIV, and global HIV strategies, feeding back into a cycle of ever-more effective programmes.