Feature Story

A lifeline interrupted in Uganda— why community health systems matter

18 July 2025

18 July 2025 18 July 2025This story was first published in the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2025 report.

In early 2025, 22-year-old Jokpee Emmanuel arrived at Reach Out Mbuya in Kampala, Uganda, expecting to attend the Friends Forum—a safe space for young people to gather, share and support each other. Instead, he was met with a sign on the gate: “Due to the suspension of United States funding, Reach Out Mbuya will be closed for 90 days. We regret the inconvenience caused.”

The Reach Out Mbuya community health initiative is not just a health facility. It is a lifeline. For years, it served Uganda’s most vulnerable communities, offering care that goes far beyond medicine. For Jokpee, who was born with HIV, Reach Out provided access to antiretroviral therapy, emotional support, school tuition and dignity. “Reach Out was like a second home,” he says. “They did not just give me medicines. They cared for me and reminded me that I am more than my diagnosis. I could live a full life.”

The closure followed a suspension of United States funding through PEPFAR, which had long supported community-led HIV responses in Uganda. The impact was immediate and severe. Community-led and community-based centres such as Reach Out Mbuya are central to public health in many low-resource settings. They offer holistic, personcentred services catered to local realities. They respond to the social, emotional and economic realities of people’s lives. These systems have been essential to the global HIV response, driving down infections and improving quality of services and life, especially among marginalized groups.

Jokpee was forced to seek care at an overcrowded Government facility. He waited six hours, only to be told antiretroviral medicines were out of stock and to return the following week. “A week without antiretroviral medicines! That is how resistance develops. That is how people die,” he says.

He eventually received a one-month supply of medicines, but the fear of another stockout remained. Although the Government of Uganda worked to fill the gap through national health facilities, it could not match the reach or personal connection of community-based programmes.

In the weeks that followed, Reach Out Mbuya managed to reopen, with support from a PEPFAR-funded programme called Kampala HIV Project. Most staff returned, restoring most of the centre’s core services. The number of clients accessing the centre is slowly increasing but is still below previous levels.

Jokpee’s story is a warning. When community-led and -based systems lose support, people fall through the cracks. If it were not for places like Reach Out Mbuya, Jokpee and his peers would be at risk of being left behind in the HIV response.

Sustained investment in community-led responses is the only way forward if we are to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Global AIDS update 2025

Region/country

Feature Story

Crowdfunding for community-led services in Fiji’s fast growing HIV epidemic

14 July 2025

14 July 2025 14 July 2025“There is no such thing as peer support here,” says Mark Shaheel Lal, founder of Living Positive Fiji. “We are starting from zero.”

When other parts of the world were wrestling with soaring HIV rates during the 1990s and early 2000s, Fiji was hardly affected. With a population of under one million, HIV remained under the radar in the South Pacific island chain.

But there has been an exponential increase in recent years. Since 2014, the number of new HIV infections in Fiji has risen ten-fold. Last year the number of newly diagnosed people tripled from 2023 levels

In January the Government of Fiji declared an HIV outbreak in response to the sharp increase in new diagnoses. Although its HIV Surge Strategy seeks to rapidly expand HIV testing and treatment, most people still aren’t accessing the services they need.

Last year just a quarter of people living with HIV in Fiji were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Concerningly, a third of those who have been diagnosed are not on treatment.

Mr Lal is among a group of stakeholders that is working not only to spread the word that HIV medicines work, but to support people to access care. He is also among the few people living openly with HIV in Fiji.

“There is this idea that you come from a small island and everyone knows each other, so the stigma here is high. I want to help reduce that,” he explains.

Dean Cassano is a Senior International Health Project Officer at Burnet Institute, an Australian public health research organization with a focus on underserved communities.

“The intervention we are proposing is a community-led response and what that looks like is peers counselling other peers. Somebody living with HIV is enabled, trained and mentored with the skills and methodology to counsel other people living with HIV. The core objective is to improve treatment adherence,” Mr Cassano explains. “We know that when someone talks to a peer they can ask about misconceptions, fears, advice on how to have a baby or how to tell a partner. They would be getting holistic support, so they know there is a way through.”

At present, people who learn they are HIV-positive in Fiji are referred to one of three sexual health clinics. Many simply never show up.

“They are too embarrassed… too scared,” Mr Lal says.

The new approach would immediately introduce newly diagnosed people to a peer counsellor. Peer counsellors would also play a key role in supporting clients as they access treatment, contact tracing, and reaching out to those who have stopped coming to the clinic.

The Institute had worked on an HIV Peer Counselling Toolkit for neighboring Papua New Guinea (PNG) where new infections are also rising dramatically. Together with Igat Hope, PNG’s main people living with HIV organization, they developed culturally specific modules. The Australian Government funded this initiative as part of the Sexual Reproductive Health Integration Project.

“There are ten topics that someone newly diagnosed with HIV needs to know about how to live well,” Mr Cassano explains.

Burnet has collaborated with partners in Fiji to adapt the toolkit, for example including local specifics in sections on food and alcohol. Fiji requires an additional module on harm reduction. Among newly diagnosed people who are currently receiving antiretroviral therapy, half contracted HIV through injecting drug use.

Now comes the next step—mobilizing and training these peer counselors. With no resources immediately available, the partners raised more than AUD$146000 through a crowdfunding campaign which ended in June. Now the training begins.

“This began as a result of us seeing a need and hearing from local partners that they want this but realizing that there is no money. The long-term plan is that this peer support is embedded into the national HIV response and is a core tenet for post-diagnosis support. Our hope is that it is sustained but first it must start,” Mr Cassano said.

Region/country

Feature Story

Cambodia becomes the second country in the Asia Pacific to offer long-acting PrEP

04 July 2025

04 July 2025 04 July 2025Borey and Sophea have both used PrEP—a medicine taken every day to avoid contracting HIV. But while this solution has worked, it was not a perfect fit.

Due to his active professional and personal life, Borey sometimes forgot to pack his pills.

“This makes it easy to miss doses, especially when I have unplanned sexual encounters,” he said.

Sophea, a female entertainment worker, is more concerned about her HIV risk with her intimate partner than at work where she uses condoms.

“I don’t fully trust that he is monogamous… he may have other partners. So, it is important for me to protect myself,” she explained.

Still, she says she’s become tired of taking a pill every day for the last six months.

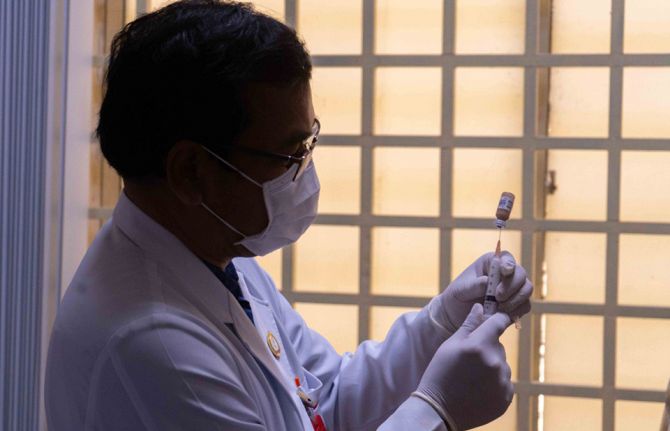

Borey and Sophia are among the first clients in Cambodia to begin long-acting injectable Cabotegravir (CAB-LA), a PrEP formulation administered every two months. With this initiative, Cambodia has become a frontrunner in the Asia Pacific region to roll out long-acting PrEP.

This HIV prevention tool is aimed primarily at groups of key populations at higher risk of HIV infection including men who have sex with men, transgender women, female entertainment workers, people who inject drugs, and couples with one HIV-positive and one HIV-negative partner. This solution is being prioritized for individuals who face challenges with daily pill adherence, those with frequent risk exposure, and those who prefer a more discrete prevention method.

“Offering multiple PrEP options enhances our ability to meet the diverse needs of individuals at risk of HIV,” explained Ouk Vichea, Director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STD (NCHADS). “Not everyone is comfortable with, or able to adhere, to a daily oral regimen. CAB-LA provides a long-acting alternative that can improve adherence and reduce stigma.”

Offering diverse and innovative HIV prevention solutions is a key strategy as Cambodia embarks on what it hopes is the final chapter towards ending AIDS as a public health threat. The country has made great progress, providing treatment to almost all people it diagnoses and achieving viral suppression among more than 98% of people on antiretroviral therapy.

However, HIV prevention remains a challenge. Every day three people are newly infected with HIV. Nine of every ten new infections occur among people from key population communities (88%). Almost half of new infections (44%) are among young people while 79% are among men.

As a young, gay man, Borey is aware of the risks and welcomes a solution he considers to be more user-friendly.

“With CAB-LA, I don’t have to worry about remembering to take a pill every day. It gives me peace of mind and helps me stay prepared and protected. It fits well with my lifestyle because I have multiple partners and don’t always feel trust. CAB-LA makes things easier, especially in situations where sex is unplanned,” he said.

NCHADS ensures that counseling is client-centered and focuses on providing clear, non-judgmental information about all available PrEP options.

“We discuss the benefits, potential side effects, dosing schedules, and how each option fits into the client’s lifestyle. We also assess their risk profile, preferences, and any barriers they may face. The goal is to support informed decision-making and ensure clients feel confident and comfortable with their choice,” Mr Ouk said.

Patricia Ongpin, UNAIDS Country Director to Cambodia, Lao PDR and Malaysia stressed the importance of choice.

“We should present people with options and ask what fits their lives. When we pair people with suitable prevention solutions, they are more likely to be consistent,” she said.

NCHADS is exploring several innovative approaches to strengthen HIV prevention. One key development is the upcoming launch of the dapivirine vaginal ring-PrEP (DVR-PrEP). This will offer women a long-acting prevention method they can control. Cambodia will be the first country in the region to make this option available.

In addition, the clinic will expand the use of digital tools for adherence support, and community-led delivery models to increase accessibility and trust. They continue to monitor advancements in next-generation PrEP products, including future injectable and implantable options, to ensure the most effective and client-centered prevention tools are available to the people who need them most.

Region/country

Feature Story

Rebuilding lives, one day at a time: A journey from addiction to recovery in Zambia

27 June 2025

27 June 2025 27 June 2025Nkumbu is 24 years old and has just finished his medical school exams in Lusaka. He’s been sober for six months. “I still can’t believe it,” he says. “Six months ago, I was wandering the streets thinking: am I ever going to make it in life? But today, I’m here.”

Growing up, Nkumbu dreamed of becoming a doctor. “There are no doctors in my family. I thought I’d become the first.” But alcohol derailed his journey early on. He began drinking in high school to overcome social anxiety. “My first girlfriend, I met her while I was intoxicated, so I thought this really worked.” What started as weekend partying turned into a habit. Eventually, his dependence led him to drop out of medical school twice.

Raised by his aunt after the death of his parents, Nkumbu recalls her heartbreak the day he was suspended from school for drinking. “She didn’t say a word on the drive home. That should have been the wake-up call. I lost faith in myself and my ability to finish medical school. I was drunkenness, day in and day out—until I found Sanity House.’’

Sanity House: A safe space to heal

Located in Lusaka, Sanity House is a rehabilitation and harm reduction centre offering a safe space for people who use drugs. Through medical, psychosocial, and vocational services, the centre builds a family-like community that helps clients heal and re-enter society with dignity and purpose. Many of the staff, including Daniel Mbazima, House Manager, are in recovery themselves and serve as mentors and role models.

Routine testing at Sanity House reveals an alarming HIV prevalence of 26% among people who use illicit drugs, compared to the national average of 11%. In Zambia, people who inject drugs (PWID) face various vulnerabilities. A 2022 bio-behavioural survey found HIV prevalence among PWID to be 7.3% in Lusaka, 21.3% in Ndola, and 12.2% in Livingstone.

According to UNAIDS, around 30,000 people injected drugs in Zambia in 2023, and 1.3 million people were living with HIV. Yet, access to harm reduction services remains limited due to stigma, criminalization of drug use, and inadequate support. In this context, Sanity House is reducing the risk of HIV infection by helping prevent addiction and giving young people like Nkumbu another chance to get back on track and pursue their life goals.

“Rehab is one day at a time. One day turns to ten, ten turns to a month. And now, six months later, I’m back in class,” Nkumbu says. “The people I used to drink with… some are dead, others are struggling to continue their studies, are in the army or even in prison.”

At Sanity House, Nkumbu found not only a way out of addiction but also restored hope. “The other patients reminded me how great I am. Thanks to them, I began to see it again in myself, to see how far I’ve come and I told myself: I got this.”

Nkumbu is now a youth advocate on Zambian television, sharing his story to raise awareness about youth and substance use. When asked about his first love, now a pilot in South Africa, he laughs. “Maybe she flew past me. I’ve got to get myself together first. I’m trending now, maybe she’s even seeing it.”

Recovery is only possible when communities are adequately supported

Daniel Mbazima, House Manager at Sanity House, has witnessed many lives transformed at the centre. “Lasting change requires sustained community support and investment,” he says “The high rate of substance use combined with a lack of integrated health services is very alarming. We urgently need programmes that link addiction recovery with essential healthcare services, particularly HIV, TB and Hepatitis C prevention and treatment, among others. Stigma remains one of the biggest barriers, preventing people who inject drugs from seeking help. Addressing these challenges demands greater support and financing for interventions like we implement at Sanity House.”

Clinton Kruger, a former client and now peer mentor at the centre, adds: “Recovery is possible. I’m the living proof of that. I want to show the world that there is hope, not only for those struggling with substance use, but also for their loved ones. Don’t give up on us. Sometimes, the care of just one person can be the only light in the darkness that addiction creates. You are not alone. Reach out. There is help, and there is a way forward.”

As we celebrate the International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking on the theme “the Evidence is Clear: Invest in Prevention” UNAIDS and UNODC call for urgent and coordinated action to decriminalize drug use and possession for personal use and to scale up harm reduction strategies and community-led programmes. Evidence shows that harm reduction, including needle exchange, opioid agonist therapy, and overdose prevention reduces HIV transmission and improves health outcomes. Yet, these services remain underfunded and inaccessible in many countries, including Zambia.

Nkumbu’s story is one of resilience, community, and the power of second chances. “I could have caught HIV, or worse. But I didn’t. I’m lucky. And now I get to help others.”

By working alongside and supporting communities, we can break the cycle of drug abuse and illicit trafficking by addressing its root causes, investing in prevention, and strengthening health, education and social support systems.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Tate Modern exhibits UK AIDS Quilt, a powerful tribute to people lost to AIDS

26 June 2025

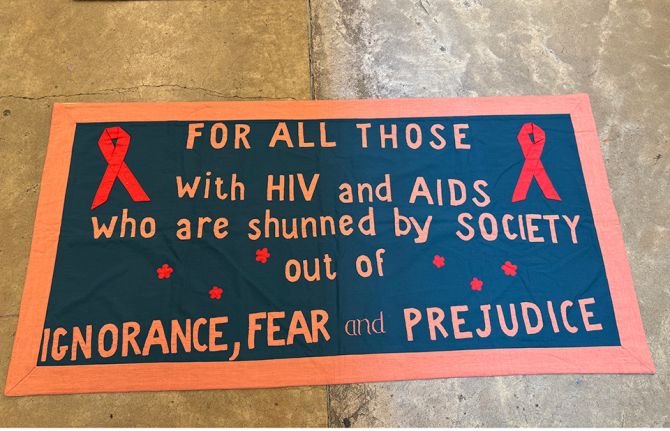

26 June 2025 26 June 2025The Tate Modern art gallery in London paid a powerful tribute to lives lost to AIDS by exhibiting the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt which features hand-stitched panels commemorating people whose lives were cut short by the disease. It is the largest ever showing of the UK Quilt in history.

On Monday 16 June UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director Christine Stegling paid a special visit to the exhibition. “It was beautiful and sombre in equal measures,” Ms Stegling reflected. “I was reminded of the loss we have all experienced. Of the dark times we have come from.”

Created in the 1980s, the UK AIDS Quilt contains 42 panels, each made up of a collection of smaller panels, created by loved ones of those who died of AIDS. The idea of an AIDS memorial quilt started in the United States as a way to commemorate the lives of people who died from AIDS-related causes. It paid tribute to friends and loved ones as sadly, those who died were often not given funerals because either their families rejected them, or funeral homes refused to take their bodies for fear of infection.

Ms Stegling’s visit underscored the importance of remembrance and perseverance, and the need to centre human dignity in public health responses. The exhibition reminds people how far the world has come in the fight against HIV—today, 30 million of the 40 million people living with HIV are on life-saving antiretroviral treatment. However, it also demonstrates profoundly that there is much still to be done to tackle the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV.

Ms Stegling’s visit was part of a broader mission to the UK. In her remarks at the British Group Inter-Parliamentary Union Pride Reception the next day, Ms Stegling warned of the devastating impact of recent funding cuts to foreign assistance, particularly the reductions in US funding and r in UK development assistance which are already undermining progress against AIDS. These cuts included defunding community-led efforts which are critical for reaching all people at risk for and living with HIV.

“Community-led efforts customized to meet the needs of LGBTIQ+ communities were among the first services defunded,” she said, highlighting the disproportionate impact on marginalized groups. UNAIDS estimates that without previous funding levels fully restored, or offset, there could be up to 6.6 million additional new HIV infections and additional 4.2 million AIDS-related deaths.

Despite these challenges, Ms Stegling emphasized the power of communities to drive progress. “Ending AIDS is no longer aspirational—it is achievable,” she told parliamentarians and civil society leaders. She called on the UK to continue its legacy of leadership by investing in equitable access to lifesaving HIV services and by supporting grassroots organizations critical for connecting people to healthcare. “Community leadership, compassion, courage—and solidarity—this is what works,” she said, urging renewed commitment to the 2030 goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat.

Ms Stegling’s UK visit, including her engagement with lawmakers and civil society during Pride Month, served as a poignant reminder that while the fight against AIDS is far from over, it can be with sufficient support for the right approaches. Her presence at the Tate Modern and her powerful advocacy at the parliamentarian reception reaffirm UNAIDS’ call to action: to fund what works, protect those most at risk, and ensure that no one is left behind in the global AIDS response.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS and Akbaraly Foundation unite to transform the HIV response in the Indian Ocean region

06 June 2025

06 June 2025 06 June 2025UNAIDS and the Akbaraly Foundation have signed a landmark partnership agreement to reshape how HIV and women’s health are addressed across Madagascar and the Indian Ocean region.

Over the past 15 years, new HIV infections in Madagascar have surged by 151%, and AIDS-related deaths have risen by 279%. Of the estimated 70 000 people living with HIV in the country, only 20% are receiving treatment. These statistics reflect lives and families in jeopardy and communities in need.

This new alliance brings together two organizations with shared goals and complementary strengths. UNAIDS brings decades of global leadership in the HIV response., while the Akbaraly Foundation offers deep community trust and a proven ability to deliver results.

“This agreement goes well beyond organizational cooperation,” said UNAIDS Country Director, Jude Padayachy, “it represents a collective commitment to innovation, equity and results that matter.”

Since its founding in 2008, the Akbaraly Foundation, which also operates in India, Italy and Rwanda, has become a pillar of healthcare delivery in Madagascar, especially in underserved regions. Its mobile unit, LUISA, has travelled more than 25 000 kilometres to provide medical services in remote villages. Over 340 000 women have been screened for cancer and 480 000 people have received life-changing education on cancer prevention.

The partnership will focus on incorporating HIV services into the fixed and mobile Akbaraly medical infrastructure to extend their reach as well as training programmes for health professionals in Comoros to strengthen the region’s response capabilities.

In addition, UNAIDS and the Akbaraly Foundation will coordinate advocacy efforts during global campaigns such as World AIDS Day and World Cancer Day to strengthen public awareness and reduce stigma. This strategic alliance is a promise to deliver health with dignity, from city centres to the most isolated islands.

Region/country

Feature Story

UNAIDS supports countries to adopt differentiated service delivery approaches to HIV care

05 June 2025

05 June 2025 05 June 2025UNAIDS has supported eight countries including Mali, Angola, Madagascar, South Sudan, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Thailand to assess the strengths and weaknesses of their HIV care service delivery systems.

If countries are to succeed in reaching the 95-95-95 HIV targets, their health systems must adopt rights-based, gender-sensitive, and people-centered models to reach the underserved populations and improve service quality.

One such model is the differentiated service delivery (DSD) approach, which is designed to provide HIV services that are adapted to reflect the preferences and needs of people living with and vulnerable to HIV, while reducing unnecessary burdens on the health system.

UNAIDS mobilized Technical Assistance Demand Generation (TADG) funding support from USAID, to bring together national program stakeholders and community groups for a data-driven consensus building process. In each country, participants used a structured health system assessment and strengthening tool, developed by the HIV Coverage, Quality, and Impact Network (CQUIN), of the Columbia University, to make informed decisions on enhancing quality HIV testing, treatment, and care services.

According to participating country teams, the exercise facilitated a breakdown of national program landscapes into clear, actionable focus areas, and improved their understanding of differentiated delivery of HIV care services. Program teams were able to prioritize areas for focus and to streamline decision-making, which will ultimately lead to practical and sustainable enhancement of HIV service provision.

“Considering South Sudan is lagging behind in treatment coverage, this was a very timely technical support exercise, that will strengthen the HIV care response to achieve 95-95-95 targets through collective action, advocacy and investment” said Dr Agai Akec, Director, HIV Programme, Ministry of Health, South Sudan.

The participating countries recognised the value of adopting differentiated service delivery approach to HIV testing, HIV treatment and the management of advanced HIV disease; establishing linkages with related services such as maternal and child health, Tuberculosis and non-communicable disease care, and promoting collaboration between health facilities and the community.

UNAIDS role has been instrumental in using US catalytic resources to mobilize partners including WHO, The Global Fund, and technical support agencies to support national government and community groups to promote a critical area of work for HIV testing and treatment.

"The TADG catalytic funding helped the country beneficiaries to demystify Differentiated Service Delivery and to identify concrete areas for improvement within national programs. I would encourage countries to undertake more of these exercises to make services available and accessible by all, particularly those who have been left behind." said Fodé SIMAGA, UNAIDS Director, Science Systems and Service for All.

For further details and guidance on using the tool, visit:

Feature Story

"We want to build a future where everyone—regardless of gender, health status, or identity—can live free from stigma and discrimination"

05 June 2025

05 June 2025 05 June 2025Ghana’s efforts to end AIDS has long relied on international support, particularly from the United States. Recent US funding cuts, however, have led to the suspension of critical programmes including human rights, raising concerns for key populations most affected by HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

In this interview, Hector Sucilla Perez, UNAIDS Country Director for Ghana, talks about the current state of the HIV response, the consequences of these funding changes, and the next steps for the country’s HIV response.

Q: What is the current state of Ghana’s HIV epidemic?

Ghana has an estimated 330 000 people living with HIV, with two-thirds being women aged 15 and over. In 2023 alone, there were 18 000 new infections and 12 000 AIDS-related deaths. The most affected groups are transgender women, men who have sex with men, female sex workers, and women. While new infections and deaths have decreased over the last decade, the reduction is far below expectations—only a 19% drop in new infections and 35% in deaths since 2010. The country needs to speed up more in the way we are decreasing new infections and deaths.

Ghana’s HIV response is heavily dependent on international donors. In 2022, Ghana's total expenditure on HIV and AIDS-related activities was approximately US$ 126 million. The Global Fund covers about 29% of this, PEPFAR (the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) about 8.5%, and the UN about 4.5%. PEPFAR support in Ghana has been essential and critical, investing more than US$ 204 million since 2007, mainly in HIV prevention, testing, treatment support, monitoring, and human rights work.

Q: What specific activities has PEPFAR been supporting in Ghana?

PEPFAR works in three regions of Ghana, (Western, Western North, and Ahafo), supporting essential catalytic services related to HIV prevention, including PrEP, as well as diagnosis, testing, treatment, and support services. They have also been supporting monitoring and evaluation to strengthen health information systems and improve data accuracy, which is critical for guiding our response.

Additionally, PEPFAR has been implementing human rights programmes with special emphasis on eliminating HIV-related stigma and discrimination. While they do not procure antiretroviral treatment in Ghana, they provide key technical assistance to the health sector on supply chain management for drugs and commodities.

Q: What has been the impact of the recent US funding cuts?

The initial pause in US government support affected activities in more than 120 healthcare sites across two regions, affecting 10 civil society organizations collaborating on PEPFAR-implemented programmes.

Some critical PEPFAR-supported actions were thereafter reinstated due to the waiver, particularly those related to the 95-95-95 targets, with a focus on vulnerable populations, especially adolescent girls and young women, and pregnant women. Monitoring, evaluation, data collection, and technical support for supply chain management were also reinstated.

However, strategic activities related to human rights with emphasis on stigma and discrimination, community-led monitoring, and interventions focusing on key populations have been definitively suspended. This represents a significant challenge for Ghana's HIV response.

Q: How is Ghana responding to these funding cuts, particularly regarding human rights programmes?

The government, through the Ghana AIDS Commission, has re-established and reinvigorated the Human Rights Stream Committee supported by UNAIDS and the Global Fund Grant. The Committee is currently to analyzing how the country can take over some of these activities. They are looking at integrating HIV more deeply into actions implemented by other government partners such as the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), and increasing collaboration with the Ministry of Gender and Social Protection and the Ministry of Labour. UNAIDS provides technical assistance in support to these efforts.

We are also supporting CHRAJ to develop a handbook on stigma and discrimination through the lens of HIV, health and rights as a sustainable way of embedding continuous professional development in the work of this Government entity on actions focused to address HIV stigma and discrimination.

UNAIDS in Ghana is also strengthening community leadership particularly networks of PLHIV and key populations to play an important role in leading harmonized CLM initiatives in Ghana in collaboration with Global Fund implementers. This is by means of technical assistance and hands on support to communities to develop concrete priorities aligned to key data gaps, including stigma and discrimination and linkages to treatment adherence.

UNAIDS has also engaged with the Global Fund to explore using efficiencies in their grants to cover these activities. The Global Fund has shown willingness to potentially develop a strategy where all stakeholders can contribute to maintaining the most relevant human rights activities in Ghana.

Q: What new initiatives are being developed to address these gaps?

The UNAIDS country office is developing an umbrella strategy called the "Ghana for Rights Initiative." We envision this as a national movement aimed at promoting and protecting human rights in Ghana, especially for those most affected by inequality, discrimination, and stigma.

This initiative goes beyond the regular framework for HIV response, focusing more comprehensively on human rights issues such as gender equality, rights of persons in vulnerable situations, access to healthcare and education, and eradication of HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

The key components are advocacy, capacity building, and community engagement, with a strong emphasis on community-led monitoring. We are accelerating discussions with country partners, including the government, bilateral donors, communities, and the UN agencies to frame human rights in a different approach and mobilize resources for the country to continue priority work on HIV and human rights intersectional agenda.

Q: What are your concerns if human rights programmes remain suspended?

Without these critical human rights programmes, we risk seeing increased stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and key populations. This could reverse progress made in encouraging people to get tested and access treatment, ultimately leading to more new infections and AIDS-related deaths.

The suspension of community-led monitoring also means we lose vital data and feedback from those most affected by HIV, making our response less effective and less targeted to real needs on the ground. This is why we are urgently working to find alternative approaches and funding sources to maintain these essential services.

Q: What is your message to the international community?

Now is not the time to step back from supporting the global HIV response. The progress we have made over the past years—reducing new infections, expanding access to treatment, and fighting stigma—has only been possible because of strong international solidarity and partnership. The recent US funding cuts have significantly impacted Ghana’s HIV programmes , especially those focused on human rights, stigma, and discrimination, which are essential to reaching the most marginalized and people in vulnerable situations .

We urge donors, development partners, and the global community to continue investing in the global HIV response especially in countries like Ghana, particularly in areas that protect and promote human rights. Without this support, we risk reversing decades of progress and leaving behind those who are most in need. Sustained international commitment is crucial to ensure that Ghana can achieve the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets by 2030 and, ultimately, end AIDS as a public health threat.

We also invite all partners to join us in innovative approaches, such as the “Ghana for Rights Initiative,” to build a future where everyone—regardless of gender, status, or identity—can live free from stigma, discrimination, and the burden of HIV.

Watch: Disruption not the solution to end AIDS

Related resources

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

“Who will protect our young people?”

02 June 2025

02 June 2025 02 June 2025Noncedo Khumalo grew up in a country with one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world, Eswatini—a country landlocked between South Africa and Mozambique. The 24-year-old has overcome her fair share of difficult times to make ends meet. The recent US funding cuts have now put her future in question.

“Young girls go for older men because when you finish high school and you want to pursue university, it becomes so hard for us, (economically) so many take a short cut,” she said.

This was how many of her friends acquired HIV. They had little awareness of HIV or how to protect themselves, she explained. She said that condom use was low and there were many myths about HIV including that it is a curse, only affecting some families.

Gender-based violence and sexual assault increase the risk of HIV infection. “In some cases, the abuser is a family member who is a bread winner, so women don’t report it,” said Ms Khumalo.

Dr Nondumiso Ncube, Executive Director of Eswatini’s National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS, says that while the country has managed to consistently reduce new HIV infections, new HIV infections remain stubbornly high amongst the younger population, particularly adolescent girls and young women who are three to five times more likely to be infected than their male counterparts. As a result, Dr Ncube says young women and girls are at the centre of the country’s new HIV strategy.

Ms Khumalo was determined not to be one of these statistics. Every day she walked almost six kilometres to attend school. She got a diploma in social work and became involved with Young Heroes, a local community organization, supported by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) three years ago.

Through this initiative, Ms Khumalo provided peer counselling to adolescents and young women about how to prevent HIV and about broader sexual and reproductive health. She visited schools and communities, offering information and support to help young people protect themselves against HIV.

Around 60% of Eswatini’s HIV response was funded by PEPFAR, however, in January the US cut all funding for HIV and issued a stop-work order for Young Heroes, forcing them to scale back their services. Ms. Khumalo lost her job.

Now unemployed and unable to reach the vulnerable young people she once served, Ms Khumalo fears for the safety of young women and girls in her community, where transactional sex between older men and young women, often motivated by poverty, and sexual and gender-based violence remain widespread. “I’m scared for the future of young people,” she said. “Without these HIV programmes, who will protect them?”

Nosipho Sacolo, a young woman living near the capital city of Mbabane expressed her fears. “After managing to stay free from HIV for so many years, we no longer have the services to protect us.”

UNAIDS Country Director for Eswatini, Nuha Ceesay says HIV prevention services—many of which are now closed—have been a game changer in Eswatini.

“Eswatini has made huge progress in preventing new HIV infections, with new infections falling by 73% since 2010,” he said.

The country still has some challenges, according to him. More than 1300 young women and adolescent girls are infected every year. And nearly twice the number of women are living with HIV compared to men.

UNAIDS and partners are concerned that the abrupt halt to PEPFAR supported HIV prevention programmes could reverse the gains that have been made.

A local network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working to ensure access to primary health care for people in Eswatini—including populations at high risk of HIV infection—CANGO, says the PEPFAR pause could have dire consequences for the country's HIV response, including a rise in new infections among young women and girls. "85 000 people were benefiting from the support, (now) all the people who were working in the sector, who were supporting our people living with HIV, are now sitting at home," said CANGO Executive Director, Thembinkosi Dlamini.

With PEPFAR’s support Eswatini had managed to ensure 93% of people living with HIV were on lifesaving antiretroviral treatment. This is one of Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Health, Khanyakwezwe Mabuza’s main concerns. “Treatment is not something you can skip,” he said. “We have to make sure that people continue to get their life-saving treatment.”

Meanwhile, Ms Khumalo is still hoping that the government and partners will not abandon the peer outreach workshops. Her livelihood and countless others depends on it as do the people they are helping to stay free from HIV.

Watch: Aid cuts hurt HIV response in Eswatini: UNAIDS fears rebound

Region/country

Feature Story

“If funding is not restored or replaced, our progress will be lost” - UNAIDS Country Director in Tajikistan amid funding cuts for the HIV response

29 May 2025

29 May 2025 29 May 2025As international funding declines, countries reliant on global support to fight HIV are being forced to adapt, and fast. In Tajikistan, the impact of these changes is already being felt. We spoke with Aziza Hamidova, UNAIDS Country Director in Tajikistan, about the country’s achievements over the years, the immediate impact of US funding cuts, and what is at stake for the most vulnerable communities.

Q: How would you describe the progress Tajikistan has made in its HIV response before the recent US funding cuts?

Tajikistan has made significant progress in its HIV response over recent years. Since 2020, HIV-related mortality has halved. Programmatic data on vertical transmission rates among women in care, suggests the rates have dropped from 2.6% in 2018 to just 0.8% in 2024, with only one case registered this year. Blood transfusion safety has been flawless for nearly 22 years, thanks to efforts by the Global Fund, UNAIDS, and other partners. Antiretroviral treatment costs have also been dramatically reduced—from US $254 to under US $65 per year—due to partnerships with PEPFAR, the Global Fund, and UNAIDS. Antiretroviral therapy is now available to all people living with HIV in the country. Outreach and awareness programmes, particularly for key populations such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, sex workers, young people, and women living with HIV, have ensured good treatment coverage and testing rates. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP-medicine to prevent HIV) had also been available and promoted through civil society organizations. Importantly, community-led monitoring had become a critical, institutionalized part of the national HIV programme.

Q: What immediate impacts have the US funding cuts had on Tajikistan’s HIV response?

While the provision of basic HIV services, including testing and treatment at state healthcare facilities, has not been significantly affected—thanks mainly to Global Fund support—there have been notable reductions in outreach and access to services for key populations. PEPFAR’s investments have been crucial in improving the quality and reach of these services. As a result of the funding cuts, outreach, access to PrEP, testing, and counselling have all diminished. Two highly popular community health centres, known for providing stigma-free services, have closed, and community services for key population groups served by these centres have been completely stopped. Community-led monitoring, a vital mechanism for ensuring programme impact and accountability, has also been discontinued.

Q: What are you hearing from communities directly affected by these closures and service reductions?

Our partners and beneficiaries are reporting the suspension of awareness work, interruptions in comprehensive support programmes, and worsening mental health. We have observed a decreased adherence to antiretroviral therapy, particularly among clients who previously relied on community-led organizations or health centres. Many individuals who were on PrEP no longer feel safe or supported and have dropped out of the programme.

In addition, skilled professionals who provided these services have faced emotional burnout and job instability, with some leaving the sector altogether. Community-led organizations that lost funding for community-led monitoring are now unable to participate meaningfully in advocacy and policymaking or the implementation of the national HIV programme.

Although PEPFAR funding for community health centres and outreach was temporarily restored at the end of April, we are still seeing reduced rates of testing and client engagement, with a number of clients lost to follow-up.

Q: How have the government and partners responded to the funding cuts, and what is UNAIDS doing to support them?

Tajikistan never planned to remain dependent on external support indefinitely.

In 2024, with UNAIDS support, the country conducted a National AIDS Spending Assessment assessment, revealing that over 60% of the national HIV programme was funded externally, mainly by the Global Fund and the US government. In response, the government, with support from UNAIDS, PEPFAR, and the Global Fund, developed its first HIV Sustainability Roadmap, aiming for national programme sustainability by 2030. The abrupt funding interruption was a shock to all stakeholders, prompting emergency actions by the government. Strategic prioritization is now underway with the support of UNAIDS, and while additional state budget funding has been allocated for 2026, it remains insufficient. Mobilizing further external resources, especially for key populations, is still necessary.

Q: What would happen if US funding is not restored or replaced?

If US funding is not restored or replaced, Tajikistan would be set to lose about 60% of its HIV programme funding. This would risk the progress that we all worked so hard for, potentially returning the country to a time when access to testing and treatment was limited. Disruptions in prevention, testing, treatment, and care would occur, and gains achieved over years of dedicated work could quickly unravel. The most vulnerable populations would be at greatest risk, and the overall effectiveness of the national HIV response would be severely compromised.

Q: What message do you have for the international community?

The HIV response in Tajikistan, as in many countries, is a testament to the power of global solidarity and smart investments. Collective action by donors, governments, organizations, communities and civil society has saved millions of lives. Now, when we are so close to the 2030 goal of ending AIDS, this solidarity must not falter. Continued support is essential to preserve progress and prevent a reversal of the gains made.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Following the US funding cuts in January, UNAIDS is working closely with governments and partners in affected countries to ensure that all people living with or affected by HIV continue to access life-saving services. For the latest updates, please visit unaids.org