Documents

Why invest in UNAIDS now? — Ending AIDS is possible, but only if we stand together

28 January 2026

Feature Story

‘I never lacked anything—except answers’ - a young man’s journey of being born with a disease he did not understand

19 January 2026

19 January 2026 19 January 2026For 24-year-old Rakhants’a Lehloibi, growing up in the rural village of Maphutseng, in Lesotho, meant navigating life with a secret he didn’t fully understand. Born with HIV, he spent his earliest years believing the antiretroviral (ARV) treatment he took daily was simply to stop frequent nosebleeds—a story his grandmother told to shield him from the stigma surrounding HIV.

“Life was tough, but my grandmother gave me all the love in the world,” he recalled. “I never felt like I lacked anything—except answers.”

Rakhants’a’s mother died when he was very young, leaving his grandmother to raise him. In 2007, when he was just 4 years old, he became severely ill. Traditional healers were consulted, but their remedies failed. It was only when he was taken to a local clinic that he was tested and diagnosed with HIV.

“Back then, I didn’t even know what HIV was,” he said. “My grandmother told me the pills I was taking were to stop nosebleeds. I believed her.”

In Lesotho—as in much of sub-Saharan Africa—stigma against people living with HIV remains widespread. Many conceal their status to avoid rejection by family and community.

“For years, I took pills but I didn’t understand why. I missed school for clinic visits. I watched my grandmother struggle just to make sure I got my medication,” Rakhants’a said. Eventually, doubting the need for treatment since his nosebleeds stopped, he began skipping doses. “I didn’t know I was putting my life at risk.”

The stigma he faced only deepened his struggle. “Kids at school whispered that I had AIDS. I felt isolated, ashamed and angry. I even thought about running away just to escape the pain. But I kept going. I passed my exams and later moved to the country’s capital Maseru to live with my sister and attend high school.”

UNAIDS country Director for Lesotho, Pepukai Chikukwa, agrees that "Though HIV stigma has reduced over the years, it is still a critical barrier to the AIDS epidemic, obstructing access to life-saving HIV prevention and treatment." Ms Chikukwa adds that it pushes people away from care and increases their risk of infection. Ms Chikukwa noted that “Addressing HIV-related stigma and discrimination requires a coordinated, multi-level, and multi-setting approach involving individuals, communities, organizations and policymakers.”

It was in Maseru that Rakhants’a’s life began to change. At Baylor Clinic, he finally learned the truth about his diagnosis and joined the Teen Club, a support network for young people living with HIV.

“For the first time, I met others like me. I realized I had been born with HIV, passed on from my late mother. That was a turning point.”

Still, the journey was not easy. Poor adherence to HIV treatment meant that Rakhants’a’s viral load was dangerously high. One health worker bluntly told him he was “as good as dead.” Placed on second-line treatment—five pills a day instead of one—he felt overwhelmed.

“At first, it was hard. But instead of giving up, I prayed every day and asked my mother to watch over me. Slowly, things changed. I gained strength, I took my medication properly, and within three months, my viral load was suppressed.”

Today, Rakhants’a uses his voice to fight stigma and inspire others. Through social media and community platforms, he spreads a message of hope and resilience.

“Being HIV positive doesn’t mean your life is over,” he said. “With proper treatment and support, we can live full, healthy lives.”

According to UNAIDS, there are 260,000 people living with HIV in Lesotho and 3200 people became newly infected with HIV in 2024. There were 6,400 children aged between 0 to 14 years, living with HIV. Nonetheless, 97% of people living with HIV know their status, of those, 97% are receiving HIV treatment and 99% of those are virally suppressed. In 2023, 11.3% of women and 18.5% of men aged 15 – 49 years old reported discriminatory attitudes toward people living with HIV.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

UN Deputy Secretary-General reaffirms commitment to a responsible UNAIDS transition and UN commitment to the AIDS response at Board meeting

22 December 2025

22 December 2025 22 December 2025The United Nations Deputy Secretary-General, Amina Mohammed, joined the 57th meeting of the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) in Brasilia, bringing a clear message: the UN will stand with governments and communities until AIDS is ended as a public health threat.

In her remarks to the Board, the Deputy Secretary-General commended the inclusive and constructive nature of the deliberations and reaffirmed that the ongoing UN80 reform process will strengthen – not diminish – the global AIDS response. She stressed that reform must be deliberate and protect what works. “There is a sense of urgency, but let me underscore here, we are not in a hurry to fail... We must achieve common ground around all the concerns that the PCB and civil society have aired over the last few weeks in particular,” she said.

Ms. Mohammed warned of growing financial pressures on countries and donors, highlighting the strain on domestic resources in low- and middle-income countries, driven by debt and the cost of debt servicing. “Governments, even if they wanted to prioritize HIV and AIDS as a budget spend, quite frankly are taking away from education, taking away from health, because they cannot meet that [cost],” she said. “Part of what we have to do today with this strategy and with the transitions that we offer in UN80 – and UNAIDS is one of them – is how to convince the international community to come back.”

The UN80 initiative aims to make the UN development system more coherent, integrated, and fit for purpose in a rapidly changing world. For UNAIDS, this means a two-phase transition that preserves its core functions and highest-value contributions to the global AIDS response – leadership and advocacy, convening and coordination, accountability and data, and community engagement.

During its meeting, the PCB adopted landmark decisions that will shape the next phase of the HIV response:

- Global AIDS Strategy 2026–2031: A bold, evidence-informed roadmap grounded in human rights, gender equality, and community leadership. The strategy will guide preparations for the 2026 UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on AIDS and negotiations for the political declaration.

- UNAIDS and UN80 transition: The Board reaffirmed its commitment to a responsible, inclusive transition of the UNAIDS Joint Programme within the wider UN development system. A PCB Working Group will be established in early 2026 to ensure the process is orderly, transparent, and safeguards UNAIDS’ core functions.

“I have seen many across the agencies that I chair in the UN Sustainable Development Group … This is a really good one. Why? Because it has so much clarity, it has so much of a division of labour, but I think that in this particular case, what has helped it is this nature of inclusion that you have had, and demonstrated, in the PCB, with civil society having such a strong voice,” said Ms Mohammed.

The PCB meeting also featured a one-day thematic discussion on long-acting antiretrovirals, highlighting their potential to transform HIV prevention and treatment. With political will, financing, and partnerships, these innovations can dramatically reduce new infections and accelerate progress toward ending AIDS.

“Ending AIDS remains achievable,” she concluded. “But only if resources match our ambition.”

Feature Story

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

22 December 2025

22 December 2025 22 December 2025This story first appeared in the recently released World AIDS Day report 2025.

In 2025, cuts in international support for the HIV response in Guatemala and a reduced HIV allocation from the Global Fund caused immediate challenges for the HIV response. Some services were curtailed or discontinued altogether in clinics affected by the cuts, and remaining service providers struggled to absorb clients who had lost their service access. Furthermore, a substantial portion of the personnel at HIV comprehensive care units and community outreach workers that help facilitate and maintain access to services for people from key populations were also affected as their work had long been funded by external donors.

In response to these cuts in external funding, the Ministry of Health stepped in to ensure continuity of care by covering the salaries of 81 staff members, thereby sustaining the operation of numerous comprehensive care units and guaranteeing service delivery to thousands to clients across the country. This intervention was critical to maintain access to lifesaving HIV treatment and preserve the integrity of the national HIV response.

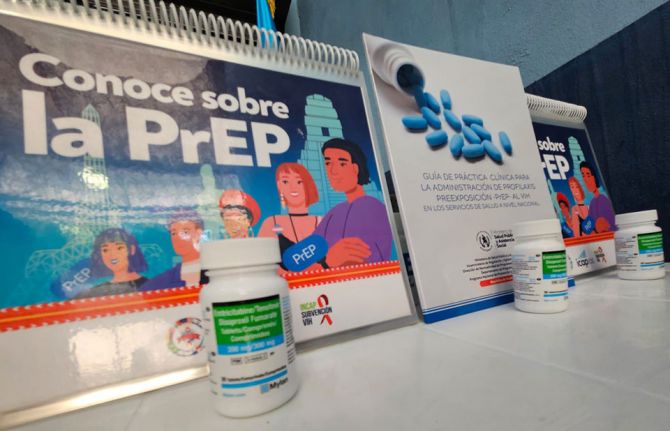

The Government also intervened to fill the gap when a key implementer and PrEP provider lost its financing. In 2025, Guatemala moved to quantify PrEP needs, develop targets for scale-up and launch access to PrEP in three departments. However, gaps persist with respect to HIV prevention programmes for people from key populations.

Community-led responses have also stepped into the breach created by the loss of international assistance. Colectivo Amigos contra el Sida (CAS), an organization focused on HIV prevention among gay men and other men who have sex with men and transgender women, moved to assume responsibility for supporting PrEP delivery to clients of a large PrEP programme that lost its funding. CAS collects voluntary donations for services from clients who can afford to pay, which helps to co-finance operational costs that are no longer covered by international donors.

Community-led responses play a critical role in the efforts to end AIDS as a public health threat. For that reason, Guatemala, with the support of UNAIDS, is working to ensure communities have access to financial and technical support. UNAIDS is collaborating with the Global Fund to help build the knowledge and capacity of civil society organizations to lobby more effectively for greater domestic resources.

Planning for the sustainability of the HIV responses is an urgent priority for many countries including Guatemala. Now that the Global Fund is set to phase out its support given Guatemala’s status as an upper-middle-income country, UNAIDS is collaborating with the Ministry of Health and the national AIDS programme to roll out the UNAIDS Rapid AIDS Financing Tool, aimed at facilitating decision-making and actions to effectively respond to the AIDS epidemic amidst a resource-limited environment.

Region/country

Press Release

New Global AIDS Strategy and Transition Working Group adopted at UNAIDS’ 57th Board meeting

19 December 2025 19 December 2025BRASILIA/GENEVA, 19 December 2025—The 57th Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) meeting concluded in Brazil this week at a time of severe disruptions to the HIV response in many countries and to the work of the UNAIDS Joint Programme. In this context, the Board adopted a new Global AIDS Strategy 2026-2031 for the world, “United to End AIDS."

“Inaction is not an option. If we stall and fail to reach the targets laid out in the Strategy, 3.3 million more people will be newly infected by 2030. We cannot allow that,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS.

During the three-day meeting, board members approved establishing a PCB Working Group to develop a plan and timeline for UNAIDS’ transition and integration into the UN system. The group will ensure meaningful engagement of all relevant constituencies – civil society, governments, Cosponsors, and other partners in-line with the UN80 initiative. “One of our key tasks through the Global AIDS Strategy, the transition of UNAIDS, and UN80 more broadly is to better understand how we can effectively encourage the international community to re-engage,” said Amina J. Mohammed, Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations. “Lives, dignity and hard-won progress are still on the line. UNAIDS has shown what collective action can achieve. This legacy must be protected.”

Throughout the meeting, PCB members and observers expressed deep appreciation for the critical role UNAIDS plays in the HIV response and UNAIDS staff. They spoke with conviction about what dedication means for governments and communities around the world.

“Brazil has reaffirmed, as a central government priority, the elimination of socially determined diseases, including the AIDS epidemic,” said Mariangela Simao, Brazil’s Vice Minister for Health Surveillance and Environment. “This agenda is grounded in our Unified Health System - universal, comprehensive and free of charge - which guarantees prevention, diagnosis and treatment across a country of continental scale and deep regional diversity,” she said.

“We cannot afford to backtrack when we made the promise to the most vulnerable,” said Erica Schouten, Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to the United Nations. "We also cannot walk away at the very moment that the HIV response needs global solidarity more than ever.”

A sentiment echoed by the North America NGO delegate. “The inclusion of NGO voices in UNAIDS is not symbolic, it is foundational to the strength and legitimacy of the Joint Programme,” said Shamin Mohamed Jr. “A premature sunset of international coordination and support is a set-back. If we do things too soon, people’s lives will end too soon as well.”

The board recognized that UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNODC, and WHO will be lead Cosponsors and ILO, UNESCO, UN Women, WFP and the World Bank will be affiliate Cosponsors.

The Strategy and the 2030 targets will inform the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on AIDS and the Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS in 2026.

UNAIDS thanked its many donors for their steady support and 2025 contributions, including: Australia, Belgium/Flanders, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Monaco, Spain and the United Kingdom.

The meeting’s thematic session on long-acting retrovirals– both for prevention and treatment – demonstrated how they can accelerate progress toward ending AIDS. With political will, financing, community leadership and partnerships, such medicines can transform the response, close the access gaps, and reduce new infections dramatically.

The 57th PCB was chaired by Brazil and going forward, the Board elected The Netherlands as Chair, the Philippines as Vice-Chair and Kenya as Rapporteur for 2026. The Report to the Board by the UNAIDS Executive Director, and the reports for each agenda item and the PCB’s decisions can be found here.The 58th meeting of the PCB will take place in Geneva on the 30th of June to the 2nd of July 2026.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.