Feature Story

Breaking barriers, saving lives: how UNAIDS has helped drafting Philippines’ landmark HIV laws

13 October 2025

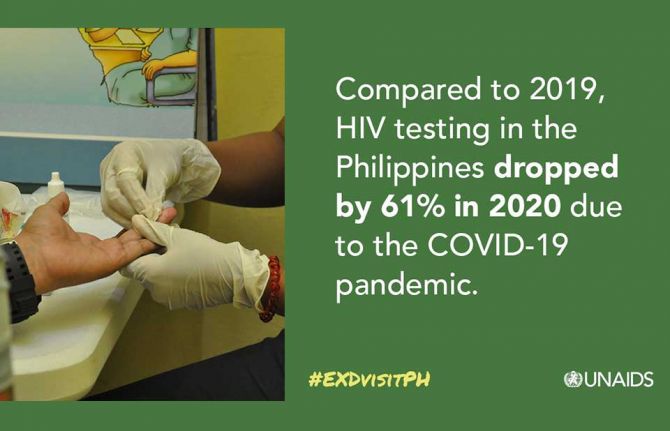

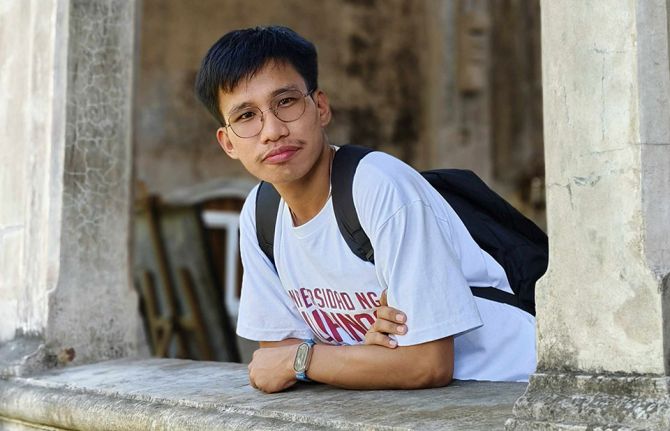

13 October 2025 13 October 2025At 17, Krang Martir stood in a clinic, alone and scared. He had decided to get tested for HIV after suspecting he may have been exposed when a trusted friend abused and raped him. But he hit a wall: the law at the time did not allow minors to access HIV services without parental consent – and he did not feel comfortable disclosing details to his parents. At that moment, even as he tried to take control of his health, the law made him wait. That wait could have cost him everything.

Thankfully, a clinic worker who empathized with him helped him get tested, which opened the door to treatment.

Today, young people in Krang’s situation no longer face that same barrier. In 2018, the Philippines passed a landmark HIV law - Republic Act 11166 - allowing people as young as 15 to access HIV testing and treatment without parental consent. The law didn’t just change policy. It saved lives. And it opened the door for a more inclusive, compassionate HIV response.

“Through RA 11166, we didn’t just protect all Filipinos, from womb to tomb, against the threat of HIV, we also provided support to the children, families, partners, and support groups of people living with HIV”, said Elena Felix, co-founder of the Association of Positive Women Advocates, Inc.

For more than a decade leading up to the law’s passage, UNAIDS worked alongside communities, government agencies, and civil society organizations to make this possible. Behind the scenes, it brought in global guidance, supported consultations, helped build consensus across sectors, and ensured that those most affected were leading the conversation.

“This wasn’t a one-year push,” said Bai Bagasao, UNAIDS Philippines Country Director from 2008 to 2016. “It took over a decade of advocacy, technical inputs, and persistent work with civil society, lawmakers, and health officials.”

The story of RA 11166 begins long before its enactment. In 1998, the Philippine AIDS Prevention and Control Act, also known as RA 8504, became the country’s first comprehensive legal response to HIV – also developed with support from UNAIDS. At the time, it was a progressive step to strengthen public awareness, establish the Philippines National AIDS Council, and enshrine into law protections for people living with HIV.

Geoffrey Manthey, the first UNAIDS Country Director in the Philippines, was directly involved in the advocacy for RA 8504. “Back then, passing the law was about breaking the silence,” he recalled. “We needed a framework that recognized HIV as a public health and human rights issue, not just a medical one. It was about protecting people who were most at risk, even when talking about HIV was still taboo.”

But as the years passed, the epidemic evolved. The virus began to spread rapidly among young Filipinos, especially among young men who have sex with men. Yet legal restrictions kept them from getting timely help.

Gerard Belimac, who once led the Department of Health’s National HIV and AIDS Program, remembers those years as a race against time. “We saw the numbers rising, especially among youth, but the law had not caught up. It didn’t reflect the realities on the ground,” he said. Many young people, afraid of rejection or not ready to talk to their families, avoided testing altogether. The result was late diagnosis, missed treatment, and sometimes lives lost.

RA 11166 was signed into law in December 2018. It did more than address the consent issue. The law streamlined testing and treatment procedures, embedded HIV education into schools, and updated national guidelines to reflect the latest global standards. It also strengthened the approach to view HIV not just as a medical condition, but also as a rights issue.

That shift continues today. In 2022 and 2023 alone, UNAIDS and its UN partners supported wide-reaching reforms. PrEP - a preventive medication - was added to the national drug formulary, enabling procurement through government channels. Over 50,000 people from key populations accessed it. PhilHealth, the national insurance provider, raised its HIV treatment reimbursement rates by 95%. And testing and treatment are expanding into new spaces, with faster turnaround times and better community-based systems.

“Laws don’t change things overnight,” said Louie Ocampo, UNAIDS Philippines Country Director. “But they create space. They legitimize what people have already been doing on the ground - and that makes a huge difference.”

Ms Felix sees the law as a symbol of how far the country has come - and how far it still has to go. “This law gave us space to be heard,” she said. “To be seen not just as patients, but as advocates.”

It’s a perspective echoed by Malou Quintos, UNAIDS Philippines’ Community-Led Responses Adviser. “We’ve moved from fear to hope. But the most powerful shift has been that people living with HIV are now leading the conversation.”

For Krang, now 26, the transformation is personal. He now speaks publicly about his experience and works to support young people who feel lost like he once did. “I wish I had this kind of law back then,” he said. “But I’m grateful it’s here now.”

Despite major successes, the work continues. Stigma remains. Many Filipinos still face barriers to care. But the path is clearer now - and more inclusive. With the United Nations celebrating 80 years of global service, the Philippines HIV response offers a striking example of how international cooperation and partnership, grounded in local realities, can deliver long-term results.

As Krang put it, “This law doesn’t just protect us, it tells us we matter. And that’s something no one can take away.”

Originally published in Breaking barriers, saving lives: how UNAIDS has helped drafting Philippines’ landmark HIV laws | United Nations in Philippines

Region/country

Press Release

At the World Health Summit, global parliamentarians meet with partners to strengthen political leadership in ending AIDS

13 October 2025 13 October 2025BERLIN/GENEVA, 13 October 2025—Parliamentarians from around the world met with policymakers and partners at the World Health Summit in Berlin to foster dialogue on how to mobilize political will, defend equal rights and build inclusive and sustainable responses to HIV.

“Parliamentarians have long been a cornerstone of international efforts to end AIDS, pushing for efforts to secure substantial funding, technical expertise, and political advocacy to ensure equitable access to life-saving HIV treatment and prevention services,” said UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima. “As we work towards ending AIDS by 2030, partnerships with governments that prioritize human rights and equity remain critical.”

The event was organized by UNAIDS, UNITE - Parliamentarians Network for Global Health, the Global Equality Caucus, and STOPAIDS, under the umbrella of the Global Parliamentary Platform on HIV and AIDS. Hosted by German MP Sasha van Beek, participants focused on reinforcing global collaboration to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 and advance human rights for populations most affected by HIV. Participants underscored the urgent need for renewed global commitment to HIV financing and to strengthening cooperation between North and South.

“Over the past 30 years, the HIV response has offered one of the greatest lessons in global health. Today, parliamentarians hold both the responsibility and the power to advance and revitalize that response. This dialogue reaffirms and strengthens that commitment,” emphasized UNITE’s Executive Director, Dr. Guilherme Duarte.

During the breakfast, parliamentarians reaffirmed their commitment to advancing policies that address structural inequalities and protect vulnerable populations. Discussions focused on improving access to HIV services, eliminating stigma and discrimination, and ensuring the protection of rights for women, girls, and LGBTQ+ people, who continue to face disproportionate barriers in accessing healthcare.

Parliamentarians also echoed UNAIDS’ call for long-acting injectable medicines that are effective in preventing new HIV infections to be affordable and available for all. UNAIDS estimates that if 20 million people in highest need, including men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs and young women and adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa have access to antiretroviral prevention medicines, it could dramatically reduce new infections and significantly advance progress towards ending AIDS by 2030.

“Game-changing medicines like Lenacapavir have created the very real possibility of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030,” said Mike Podmore, CEO of STOPAIDS. “However, overseas development aid reductions risk undermining our ability to realize this opportunity and even reverse existing progress. Parliamentarians, uniting in partnership around the world through mechanisms like The Global Parliamentary Platform for HIV, are essential voices to make sure their governments play their part and invest now to reach the incredible goal of ending AIDS.”

Parliamentarians from Germany, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mexico, Namibia, Sweden, the United States, Uganda and Zimbabwe participated in the event which took place on the opening day of the World Health Summit.

"An equitable HIV response should remain a key priority in the actions of governments to address the disproportionate impact that HIV has on marginalised communities, such as LGBT+ people,” said Aron le Fèvre, Executive Director of the Global Equality Caucus. “Parliamentarians have an important role holding governments to account, and forums such as the Global Parliamentary Platform are crucial to developing the partnerships needed to support lawmakers in their parliamentary and policy advocacy."

As the World Health Summit continues, UNAIDS will underscore the importance of sustained political leadership, international cooperation, and human-rights-centred approaches in the fight against AIDS.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook X Instagram and YouTube.

UNITE

UNITE is a non-profit, non-partisan global network of current and former members of parliament from multinational, national, state and regional Parliaments, Congresses, and Senates committed towards the promotion of efficient, sustainable and evidence-based policies for improved global health systems in alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The network currently has over 520 Parliamentarians in 119 countries. Learn more at unitenetwork.org and connect with us on LinkedIn,Facebook, X, and Instagram.

Contact

UNAIDSSophie Barton-Knott

tel. +41 79 514 6896

bartonknotts@unaids.org

UNITE

Ana Filipa Cruz

anafilipavc@unitenetwork.org