Feature Story

Hundreds of thousands of people commemorate Zero Discrimination Day on OK.ru

06 March 2018

06 March 2018 06 March 2018On the eve of Zero Discrimination Day on 1 March, more than 890 000 viewers joined the online platform OK.ru/test to discuss zero discrimination and join the launch of the UNAIDS regional #YouAreNotAlone campaign. The discussion was live-streamed on Odnoklassniki, the leading Russian-language social media platform for countries across eastern Europe and central Asia.

The #YouAreNotAlone campaign is raising awareness about the stigma and discrimination faced by children, adolescents and families affected by HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia. The campaign features young Russian artists who each retell the personal story of an adolescent living with HIV in the Russian Federation. Most adolescents in eastern Europe and central Asia still face stigma and discrimination that prevents them from being open about their HIV status.

The broadcast also featured an interactive online film, It’s Complicated. Based on the lives of adolescents and young people living with HIV in the Russian Federation, the film tells the story of Katya, a Russian girl born with HIV who faces stigma and discrimination but also finds love and support as she grows up and adjusts to life with HIV. Some of the film’s crew and lead actors joined UNAIDS and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization staff in the OK.ru discussion.

“The goal of the #YouAreNotAlone campaign is to promote solidarity with children, adolescents and families affected by HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia for them to live with safety and dignity,” said Vinay P. Saldana, Director for the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The campaign has been promoted through social media by Vera Brezhneva, UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Victoria Lopyreva, UNAIDS Ambassador for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, and others. Everyone is encouraged to support the campaign by posting a photo on social medial with the hashtag #тыНЕодинок (#YouAreNotAlone).

“These young people are inspiring and strong,” said Ms Brezhneva. “Something is very wrong with a society where the human rights and dignity of people living with HIV are not respected. Every person living with HIV should feel our support, #YouARENotAlone!”

The campaign was also launched in Armenia, where it was supported by actors, television presenters and others. Armen Aghajanov is the first person living with HIV in Armenia who publicly disclosed his HIV status during the launch of the #YouAreNotAlone campaign on Zero Discrimination Day. He said: “People are not dying from HIV, they die from discrimination, late diagnosis, lack of access to treatment or from not taking medicines.”

Film

Region/country

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Albania

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Estonia

- Georgia

- Hungary

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Montenegro

- Poland

- Republic of Moldova

- Romania

- Russian Federation

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Tajikistan

- North Macedonia

- Türkiye

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- Uzbekistan

Related

Feature Story

The moment of truth in breaking down barriers

27 February 2018

27 February 2018 27 February 2018When Robinah Babirye was at boarding school, her secret was difficult to hide. Sleeping in an all-girls dormitory, everyone knew everyone else’s business, especially around bedtime. “It was hard to bring out my medicine,” she said. “It would raise questions.”

Ms Babirye and her twin sister were hiding their HIV-positive status. Before starting at boarding school, the daughters and their mother would take their medicine daily at 10 p.m., and that was all there was to it.

Once she enrolled at university in Kampala, Uganda, in 2013, hiding became more difficult. Her room-mate was suspicious and spread rumours. Having been born with HIV, she couldn’t help feeling that life was unfair.

“At the time, I hadn’t accepted that I was living with HIV and that I had to live with it for the rest of my life,” said Ms Babirye. She described years and years of avoiding ever speaking to anyone about her regular visits to the clinic or about taking treatment. Then her mother died from cancer and she didn’t know how to cope.

Glancing above her eyeglasses, she added, “When I saw my mother fighting, it gave me strength, but when she died that became a terror.”

Ms Babirye more or less gave up. She stopped taking her medicine and drifted.

Asia Mbajja, founder and director of the People in Need Agency (PINA), a nongovernment organization for young people living with HIV in need, described appeals from distraught teenagers. She had helped many of them as children while working as a treatment coordinator at the Joint Clinical Research Centre children’s clinic.

“I kept promising them that life would change and get better, but as they grew up, their needs changed,” she said. “I needed to do something that would make a difference.”

In 2012, Ms Mbajja quit her job to start PINA. Among her first clients was Ms Babirye, whom she has known since the age of 10. She hammered over and over the importance of taking the daily dose of antiretroviral therapy.

“The problem is that all of Asia Mbajja’s upbeat encouragement would come tumbling down once she was no longer around,” Ms Babirye said. The young woman felt defined by HIV.

“When you're told that you have to take medicine for the rest of your life, coupled with the rumours and stigma, I feared I would forever be stuck,” she said. “Despite living with HIV, I am still a woman with feelings.”

Through her involvement with PINA, in 2014 Ms Babirye travelled to the International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia. The young woman felt elated to discover a world where her status seemed a non-issue, but upon her return she couldn’t help feel like there was a line she could not cross.

Ms Babirye felt tired. She wavered between ending her life and changing her life for good.

Donning an I am HIV Positive t-shirt she posted a photograph of herself on Facebook. “My heart started to beat so fast, I couldn't bear to see the comments,” she said. She paused and let out a gasp and said, “I was expecting a lot of negativity, but the comments were largely positive.”

Her twin sister, Eva Nakato, couldn't believe what she had done. After some thought, she decided she couldn’t let her sister fight alone, so she also disclosed her status.

“When people said we need more people like her it motivated us,” said Ms Nakato.

One of the first people to congratulate the twins was Ms Mbajja. Ever since, the duo have been at the forefront of PINA, testifying, mentoring and singing. Ms Nakato explained that at the children’s clinic they used to sing as a group, and at PINA they brought it to a whole new level.

“We started using music to convey HIV awareness messages," she said. Songs like Never Give Up, Yamba (Help) and ARV. Their latest projects now include launching a television series around HIV and relationships and documenting gender-based violence.

“When we met survivors of sexual abuse, that pushed me to make a movie,” Ms Nakato said, adding that videos and music can get messages across.

Ms Babirye finished her university degree last year and dreams of independence.

In the long term, she said her vision is a generation that is AIDS-free and stigma-free. “To accomplish an AIDS-free world, each individual has a responsibility to do something and break down cultural and societal barriers,” she said.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Becoming an activist to overcome discrimination

28 February 2018

28 February 2018 28 February 2018Thrown out of the house by his parents when they found out he was gay, Ezechiel Koffi didn’t give up.

“My parents said I shamed them and that I lived the life of a sinner,” the young man from Côte d’Ivoire said. What hurt him the most were his mother's insults, saying he had no respect for their religious values. He begged them to understand that he was their son and that they should accept him as he was.

Mr Koffi, 24 years old at the time, stayed for a while at Alternative, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people nongovernmental organization in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, where he had started volunteering three years earlier. He kept going to classes, although admits that at times he went on an empty stomach. Psychologically he felt beaten. “It was hard, but I couldn't hide anymore,” he said.

With the help of his older sister, his parents let him move back home after six months. Although he now had a steady roof over his head and regular meals, Alternative became his second home. He has been dedicated to it ever since. Now an HIV educator and community health worker, he proudly showed his certificates on his mobile phone.

Alternative’s project coordinator, Philippe Njaboué, describes Mr Koffi’s tireless energy. “You can call him at whatever time, day or night, he always lends a hand and he often goes out of his way to include people who have been shunned.” When asked about being a substitute family for many LGBTI people, Mr Koffi gave a hesitant smile.

The many discussion groups and support groups have helped, he said, allowing him to share his experience and help others. The once shy boy has emancipated himself. He also no longer shies away from revealing his HIV status. “It’s been 10 years now that I have been living with HIV,” he said.

Looking back, he explained, in the beginning he couldn’t always negotiate the use of a condom. He now makes a point of telling everyone that HIV is a reality. “Use condoms, there is help, you are not alone,” he exclaimed.

He described feeling fully alive among the city’s tight-knit LGBTI crowd. “I am at ease, I can express myself and it’s fulfilling,” he said. His brow furrowed, however, when he mentioned the constant discrimination he and his peers lived with. On top of the taunting and the finger pointing, Mr Koffi said social media was rampant with homophobic comments.

“We deserve the same rights as everyone else and that’s what keeps me motivated,” Mr Koffi said.

Mr Njaboué remarked that society, religion and the state all play a big part in keeping homosexuality taboo in Côte d’Ivoire. “A recent speech by Alternative’s director was tagged by a website as “The king of the homosexuals speaks”, which led to countless death threats,” he said.

Noting that this case was one of many, he believes the situation can only change if the government tackles human rights.

“Most of the population doesn’t know their rights or the law, including a lot people in charge of state security,” Mr Njaboué said. “Not only does the government need to educate people, it should also condemn unlawful behaviour,” he added.

For Mr Koffi, his visibility puts him at risk, he said, but he forges ahead. “I want to live in a world where there is no discrimination based on one’s race, one’s religion or one’s sexuality.”

Region/country

Feature Story

Pili movie focuses on the universal aim for a better life

28 February 2018

28 February 2018 28 February 2018Carrying a hoe over her shoulder as she ambles along a dirt road, Pili, a young Tanzanian woman, eyes an empty market stall. Talking to her friend while clearing a field, she says, “Digging all day, fighting for money, I can't do this my whole life.”

So begins the movie Pili, which focuses on a single mother with two children trying to make a better life for herself and her family. Farm work pays less than US$ 2 a day and the 25-year-old has a hard time keeping up with childcare, school supplies and medical check-ups. Pili lives with HIV and struggles to keep her HIV status a secret. She fears stigma and is scared that she will not get a loan to pay for the market stall she dreams of renting.

Produced by Sophie Harman and directed by Leanne Welham, the movie draws you into Pili’s daily struggles to gather money to become her own boss. Spoiler alert: she succeeds, but at a cost.

Ms Harman, an academic at the Queen Mary University of London, never dreamed of making a film. But she realized that a movie could be a collaborative project that would enable her to highlight the plight of many women.

“When I teach, I often have used film, which is very impactful, so I wanted to do my own film, but as a realistic feature based in Africa,” Ms Harman said.

In 2015, she won an AXA Insurance Outlook Award in recognition for her work in global health politics and HIV governance. The award gave her the money, but she needed a movie director—film-makers were wary about producing a film with untrained actors on a shoestring budget in the middle of nowhere. Within a year, though, she met Leanne Welham, a short-film director with years of experience in Africa.

What clinched the deal was Ms Harman’s access to the communities among which the film was to be made. Having started a nongovernmental organization in 2006 called Trans Tanz, Ms Harman had been inspired by women’s stories. Trans Tanz provides free transport for people living with HIV in rural areas so they can go to clinics.

Ms Welham and Ms Harman pitched their movie idea to the community and started compiling stories based on real-life experiences.

“To protect the women, we stressed to everyone that this would be a story based on our 80 interviews and my research,” Ms Harman explained. The community approved and gave feedback on the screenplay.

They now needed characters and to cast the leading actress, Pili. During an audition, Ms Welham met Bello Rashid, who had come to the session out of curiosity with her older sister. The young woman overcame her shyness and responded well to direction and landed the role.

Because of the language of the movie (Swahili), and the varying degrees of literacy, the British film crew mixed improvisation with a script. The film was set in Miono, a village near the Tanzanian coast.

“The cast are all real people, with only one trained actor, and 65% of them are living with HIV,” explained Ms Harman. “I wanted to protect the women and make this as anonymous as possible while still reflecting the daily grind.”

The five-week shoot in early 2016 taxed everyone.

“We not only had a very tight budget, we also dealt with illness, funerals and attempted extortion,” Ms Harman said. Reflecting on this, she said it created a heightened sense of camaraderie.

What struck Ms Welham was the amount of time it takes for people to get around. “The concept of time and the impact it has on one’s life cannot be stressed enough,” she said.

“As a filmmaker, I wanted to show the tranquil pace of Miono, but also the frustration and isolation too,” Ms Welham said. Pili walks to the field for 40 minutes then walks back the same distance. To get to a health clinic where no one will recognize her from the village she has to take a bus. It breaks down on the way back so she is late to pick up her children and nearly misses her meeting with the council of women who approve micro-loans. All of this in the blistering heat.

The movie premiered in September 2017 and then played in Geneva, Switzerland, as part of the World AIDS Day celebrations on 1 December. It won two awards at the Dinard British Film Festival and was part of the official selection at the Pan African Film and Arts Festival. The movie will be screened in British cinemas in the first half of 2018, with all the proceeds being given to the Miono community.

Since filming the movie, Ms Rashid has decided that she wants to stop working in the fields and to study to become a nurse.

Ms Welham is particularly proud that the movie allows viewers to step into a world they may not know about and see that, despite the poverty, the issues remain the same. Her producer agrees. “The important part of Pili is that it’s a universal story,” Ms Harman said. “You might not be HIV-positive or live in rural Africa, but everyone can associate with wanting something better for their life and their children.”

Multimedia

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Supporting the rights of sex workers in Côte d’Ivoire

01 March 2018

01 March 2018 01 March 2018Singing “akouaba” (welcome), a group of young women crowded around Josiane Téty, the director of Bléty, a Côte d’Ivoire organization led by sex workers, as she arrived.

Located in Yopougon, a suburb of Abidjan, Ms Téty explained that in the centre one of the first things they do is give each other nicknames. Names such as Joy, Hope or Chance, because women, she said, often need a confidence boost and a sense of a new beginning.

“We take the time here to work on self-esteem, so that all the girls believe in themselves,” she said.

Most of the women at Bléty are current or former sex workers who carry out peer outreach, ranging from HIV awareness-raising and education about HIV prevention to promoting sex workers’ rights and continuing education.

“We seek to give young women opportunities and alternatives so that they are less vulnerable,” Ms Téty said. Pointing towards a young woman, she said that Happiness had started beginner accounting classes.

Ms Téty and other sex workers founded Bléty in 2007 because they realized that they had little information regarding their health or their rights and hated feeling stigmatized.

“Getting an HIV test doesn’t mean that you are living with HIV, but that is how we were perceived when we were seen leaving a clinic,” she said.

They set out to correct that and have implanted themselves in the community.

Marie-Louise Sery came to Abidjan to work following her parents’ death. She didn’t have much schooling and finding a job was difficult, so she started sex work. The 30-year-old, wearing braided pigtails, admitted being completely clueless about the risks she took.

“Bléty got me out of that situation,” Ms Sery said. This past year she became one of Bléty's peer educators.

Most of the time, she said, peer educators target bustling street corners to talk to sex workers, of which there are estimated to be more than 9000 in the country. Aside from handing out condoms, they also conduct rapid HIV tests and hand out cards with the contact details of Bléty’s various focal points, who can be reached day and night in the event of an emergency.

“My work involves giving a lot of support and hand-holding,” Ms Sery said.

Sex work is not illegal in Côte d’Ivoire, but the laws on it are vague. As a result, there is abuse and sex workers are vulnerable to violence. “We really stress to our friends out there that because they’re sex workers, it doesn’t mean people can take advantage of them,” Ms Téty said. If they have been abused they can call a Bléty peer educator and are accompanied to the police station or to the hospital.

Ms Téty said a recent victory had been to negotiate with doctors and health-care providers to provide a medical certificate free of charge, instead of for a US$ 35 fee. The law in the country requires a medical certificate in order to pursue a criminal case.

In its 10-year existence, Bléty has fended off pressure from the police and residents to change their attitudes towards sex work. Bléty has educated the police as well as sex workers in order to break the climate of mistrust between them.

“We have established good relationships with uniformed police, but there is a high turnover, so it can get frustrating to start all over again,” Ms Téty said.

Overall, she remains optimistic. Testing for HIV and sexually transmitted infections among sex workers is up, lawyers have stepped in to give legal advice and she sees her centre growing further.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

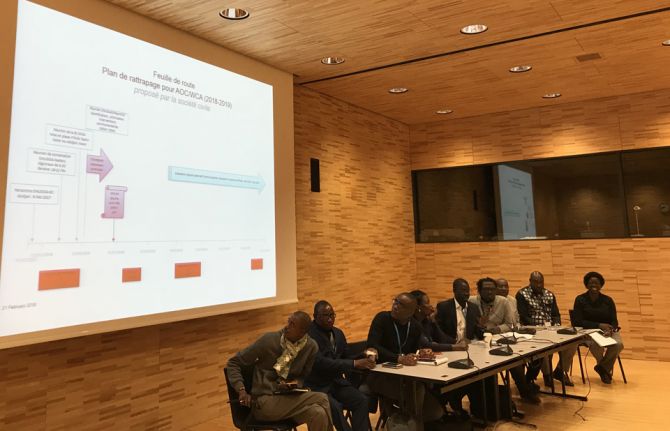

Civil society has solutions that UNAIDS and partners need to harness

21 February 2018

21 February 2018 21 February 2018Civil society leaders from western and central Africa have laid out a road map to take a more active role in scaling up HIV prevention and treatment services in the region. The eight leaders reiterated that without their involvement and help, it would be difficult to reach people and the treatment goals.

“We want to be more involved, because we are on the ground and we are the people concerned,” said Daouda Diouf, Director of ENDA Dakar and rapporteur of a three-day meeting of civil society, UNAIDS and partners held from 19 to 21 February in Geneva, Switzerland.

In 2016, the western and central Africa region faced disproportionately high AIDS-related deaths compared to its share of the world’s population. Although HIV prevalence in the region remains low, few people living with HIV there have access to treatment.

The leaders pointed out the many challenges they face. In many francophone countries, medical care remains too centralized, carried out mostly in clinics, limiting outreach from peer educators and community workers. They also said that stigma and discrimination keeps people away. National health policies often do not allow civil society to deliver key services, such as HIV testing.

Hidden fees for health services paid by the patient also dissuade people from seeking help. And funding and political will have waned in recent years, reducing their capacities.

Aliou Sylla, Director of Coalition Internationale Sida-Plus, stressed that civil society has many solutions and experience from pilot programmes that have been proven to work.

“Because we have clinics that do not look like clinics, because we do peer-to-peer HIV testing and because we offer counselling, we are much more capable of reaching vulnerable people,” he said. “Just have confidence in us.”

His colleague wholeheartedly agreed. Ibrahima Ba, coordinator at Bokk Yakaar, a nongovernmental organization and leader of the regional network for people living with HIV, added that not only can civil society reach people, it can also monitor the progress of national and regional HIV plans. “Count on us to be implementers, but also watchdogs, so that governments are held accountable.”

The road map includes an upcoming regional meeting bringing together civil society from 12 western and central African countries in order to incorporate their views in national HIV plans. UNAIDS will be advocating for them to have more influence in countries.

In closing the meeting, Deputy Executive Director Luiz Loures said, “The data and the evidence show that we are not optimizing our efforts in the AIDS response in this region.” Looking at the civil society leaders, he concluded, “We need to use civil society as an engine.”

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Partnership connects African law schools to the AIDS response

26 February 2018

26 February 2018 26 February 2018Stigma and discrimination, especially against women and girls and key populations, is a major barrier to people using HIV services. Up to 60% of countries report having laws, regulations or policies that deter people in key populations from being able to protect themselves from, or get treatment for, HIV.

There is therefore a need for legal services to challenge stigma and discrimination, but in many parts of the world such services are absent. Since teaching in law schools is often focused on core subjects, such as constitutional, administrative and criminal law, that often do not address legal issues related to HIV, most lawyers lack the specialized knowledge they need to take on HIV-related stigma and discrimination cases.

Academics sometimes need to give advice on key HIVrelated legal issues, such as the criminalization of HIV transmission. It is therefore important that they understand why human rights are essential to the response to HIV.

To respond to this lack of HIV-related legal knowledge, a unique pilot project has been set up with the law schools of the Universities of Dar es Salaam and Dodoma in the United Republic of Tanzania and Makerere University and Uganda Christian University in Uganda. The project will strengthen the legal environment for the response to HIV and give academics and students the skills they need to support human rights-based responses to HIV. It will also increase awareness in order to encourage communities to seek support from legal clinics.

“By training a committed and well-informed future generation of lawyers on HIV and the law and informing people about their rights, UNAIDS hopes to strengthen a human rights-based response to HIV in the United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS.

The project is the result of an agreement signed in 2014 by UNAIDS and the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) to scale up efforts towards zero HIV-related discrimination. The project is part of a collaboration that started in 2009 to strengthen and expand legal services for people living with HIV and key populations.

“HIV is not just a health issue, but a matter of social justice. It’s crucial that we equip the next generation of African lawyers with the knowledge and skills to effectively respond to HIV and end discrimination,” said Irene Khan, Director-General of IDLO.

The project will also see legal handbooks being developed for both the countries, which will serve as guidance on HIV and the law for students, lawyers and community leaders. The handbooks will consider HIV epidemiology in the region, the social and legal factors that contribute to HIV vulnerability, jurisprudence and common legal issues faced by people living with HIV and key populations. They will also give legal and non-legal options to address these issues.

“The project has exposed our students to new skills in responding to the challenges facing people living with HIV. The legal clinic now has the necessary skills to provide services to people living with HIV in Dodoma,” said Nicodemus S. Kusenha, a Lecturer at the University of Dodoma in the United Republic of Tanzania.

A UNAIDS, United Nations Development Programme and IDLO collaboration that started in 2009 has provided technical and financial support to HIV-related legal services in 18 countries and produced a publication on scaling up HIV-related legal services and elearning courses in four languages.

“Through an interaction with people living with HIV and key populations, we have been able to draw links between the theory of health law as we teach it and the beneficiaries of the law. This project has therefore made our teaching of the law more meaningful and with a human face,” said Zahara Nampewo, a Lecturer at Makerere University in Uganda.

Related

Feature Story

Preventing and treating HIV in Saint Petersburg

20 February 2018

20 February 2018 20 February 2018According to the Centre for AIDS Prevention and Control in Saint Petersburg in the Russian Federation, fewer people are becoming infected with HIV in the city. “Ten years ago, Saint Petersburg was among the top five most affected cities in the Russian Federation. Now it is only the 14th most affected,” said Denis Gusev, Head Physician of the AIDS centre. “Saint Petersburg is the first urban metropolis in the Russian Federation where a steady decline in new HIV infections has been recorded,” added Vinay P. Saldana, Director, UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

In 2017, there around 1750 people newly diagnosed with HIV in the city, compared to nearly 2200 in 2015. In total, about 42 000 people have been diagnosed as living with HIV in Saint Petersburg, 80% of whom access services at the Centre for AIDS Prevention and Control. The AIDS centre provides not only antiretroviral therapy, but also a full range of specialized medical care and HIV prevention services.

Artem Vereshchagin, who answers calls at the AIDS centre’s hotline, has been a client of the centre for more than 18 years and more recently an employee. He notes that more and more people who call the hotline now ask practical questions, such as “How do I get HIV treatment” and “How much time is needed to get an undetectable viral load”.

Saint Petersburg is one of the few cities in the Russian Federation that provides patients with virtually the entire range of HIV prevention and treatment services, including harm reduction. Prevention services are available at the city AIDS centre, where people can exchange syringes and get sterile equipment and condoms.

Quick testing for HIV is important, according to Mr Gusev, who says that the majority of people who are diagnosed with HIV in Saint Petersburg get immediate access to HIV treatment. “The main thing is for a person living with HIV to see a doctor and start antiretroviral therapy. Then we save a person’s life and help prevent new infections,” he said.

Saint Petersburg provides services for key populations, both in mobile clinics, in partnership with community-based organizations, and at the AIDS centre. “Women can get tested for HIV, receive condoms free of charge and talk to peer consultants,” said Irina Maslova, of the Astra Foundation, which works with female sex workers.

The Centre for AIDS Prevention and Control’s Department of Motherhood and Childhood provides services for women and children affected by HIV. The current level of mother-to-child transmission of HIV at the centre is 1%, but the staff want to reduce that to zero.

Saint Petersburg’s residents have been learning about HIV prevention services from a large outdoor advertising campaign and public service announcements across the city, supported by the city government. The advertising has three key messages—on HIV testing, the availability of HIV treatment and the elimination of all forms of stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV.

Credit for all photos above: UNAIDS/Olga Rodionova

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

A champion for screening and treating cervical cancer among women living with HIV

08 February 2018

08 February 2018 08 February 2018Basilisa Ndonde has a big smile on her face as she walks into her office at Tanzania Health Promotion Support, a civil society organization. It is a special day for her—World Cancer Day, commemorated on 4 February each year. Ms Ndonde is at the forefront of the response to cancer on the ground, coordinating the Afya Jali project to raise awareness about, and uptake of, cervical and breast cancer services among women living with HIV.

Women living with HIV are four to five times more likely to develop cervical cancer than women who are HIV-negative. HIV weakens the immune system and reduces the body’s ability to fight opportunistic infections, such as the human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes 70% of cervical cancer cases.

The United Republic of Tanzania has the sixth highest incidence of cervical cancer in the world and has 1.4 million people living with HIV.

Ms Ndonde is proud of the achievements of the Afya Jali (which means “Taking care of your health” in Swahili) project so far, just a few months after its inception. In collaboration with the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children and the Tanzania network of women living with HIV, Ms Ndonde has facilitated the development of resource materials for health and community workers to sensitize women on the need to be screened for cervical and breast cancer. “For the first time in the country, we now have comprehensive guidelines for health workers on the prevention, screening and treatment of the cancers of reproductive organs,” she says.

Ms Ndonde has obtained the support of local government authorities in all four regions in which the project has been implemented. She has also organized a training of trainers workshop in the same regions for 30 women living with HIV, who sensitize other women on cervical and breast cancer and encourage cancer disclosure to mitigate stigma. “Each participant had to practice and demonstrate in front of the workshop’s audience that they know how to deliver the messages back to their respective communities,” says Ms Ndonde.

The project is funded by UNAIDS as part of the Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon (PRRR) initiative, a global partnership of governments, nongovernmental and multilateral organizations, foundations and corporations with a shared goal of reducing deaths from cervical cancer and breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries. PRRR’s mission in the United Republic of Tanzania is to build on existing health-care programmes to integrate cervical cancer prevention, screening and treatment and breast cancer services and to increase access to HPV vaccination.

UNAIDS is working with countries to achieve the commitment made by counties at the United Nations High-Level Meeting on Ending AIDS in 2016 to take AIDS out of isolation through people-centred systems to improve universal health coverage, including treatment for tuberculosis, cervical cancer and hepatitis B and C.

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Promoting women's leadership in science and health

09 February 2018

09 February 2018 09 February 2018The International Day of Women and Girls in Science is celebrated on 11 February. As part of UNAIDS’ Right to Health campaign last year, UNAIDS Special Ambassador for Adolescents and HIV and champion for young women in science, Quarraisha Abdool Karim, spoke with her daughter about her life’s work and the importance of women’s involvement in science and health.

Mother and daughter, Quarraisha Abdool Karim (Q), the Associate Scientific Director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, and Aisha Abdool Karim (A), a student at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, spoke about health and what that means for young women in South Africa.

A: For me, growing up I was surrounded by science and it was part of my daily life, but what got you interested in science and health?

Q: Probably for most of my life I thought about science and its application to leaving people better off. So, I wanted to be a scientist and I wanted to do something that would help people.

A: Science continues to be a male-dominated field, like many others, so I feel like you brought an interesting perspective to your research. How do you think your experience as a young woman influenced your research?

Q: My very first study, when I was relatively young, 28, was when I did the first population-based survey in South Africa. The data were very clear, that young women had a four-times higher HIV infection rate than young men and that women acquired HIV about five to seven years earlier than men. And that intrigued me a lot and I spent the next 20-odd years trying to really understand that better. To understand why young women were getting infected but not young men and to understand what some of the factors were that were influencing young women to become sexually active.

A: It’s interesting to me that you chose to focus on understanding why women are becoming sexually active, because I feel like my high school education was very focused on abstinence. Even though we did have a version of sex education, it wasn’t very informative or useful. Do you feel like there’s been a change in education around topics like reproductive health since you were in school?

Q: You know, I grew up in a much more conservative era, where having relationships in high school and being sexually active were much more frowned upon. But I think that teachers still feel very uncomfortable talking about sexual health and choices and generally about reproductive health issues in South Africa, or, I would go so far as to say, in Africa.

A: I agree, I think there's still this hesitance to discuss sex openly at school. While the topic of sex might not have been off limits in our home, it definitely made some of my friends uncomfortable if I brought it up in conversation.

Q: You’re reminding me of something else that I’ve learned in working with young people, which is that they don’t like getting information from adults and people they’re familiar with. They're more comfortable getting information from their peers. It shows how knowledge is important, but also how it’s viewed in the community and how the society you live in influences your ability to act.

A: Well, you’re talking about the role of the community, which extends beyond just education and policies. Nowadays, I think people are becoming more aware of the intersectionality of issues and health is no exception. Young women have been a central part of your research. What are some of the other factors that affect their lives?

Q: I’ve learned that the vulnerability of young women is very much tied into gender power differences in society and these disparities are very important for perpetuating the vulnerability of young women socially, economically and politically. And that extends way beyond HIV.

A: The reality of gender power dynamics is something I only really began to understand when I was at university, because it wasn’t really an issue for me when I was at my girls high school. Do you think that the political landscape of South Africa changing to a democracy has had an impact on these gender dynamics?

Q: Although the politics has changed, that has not been translated to the grass-roots level. Younger women needed to understand that they are now in a different world in South Africa, with many more opportunities.

A: That comes back to the idea of gender dynamics and community. I feel that there’s this idea of girls lacking independence and that makes it more difficult, especially for young women, to feel like they can make their own decisions when it comes to their bodies.

Q: So, I think there is this tension, and I think you are in a better position to talk about women of your age or younger. There used to be this thing about how women should be ignorant about their bodies and their partners will be able to tell them everything. Whereas I think to be empowered, you actually need to know about your own body. It’s so important for young women to have access to information about health. We need to be encouraging an attitude where young women are no longer ashamed to know about their own bodies. Do you think there’s a way we can address this?

Q: Having a social environment that is supportive of those norms is critically important, because young women themselves have very little agency. But in order to create that climate and context, it will necessitate men taking greater responsibility, boys taking more responsibility for themselves and their behaviours.

A: Education is such a key part of creating that environment and addressing the topic of health. Being able to see the impact that your research had on public perceptions gave me a sense of the power that information can have and was part of the reason why I decided to be a journalist. This is something particularly important in this day and age, when we need to combat the spread of misinformation and debunk myths in health care and beyond.