Feature Story

Peer consultants helping the AIDS response in Kyrgyzstan

10 June 2020

10 June 2020 10 June 2020When the son of Kymbat Toktonalieva (not her real name) was finally diagnosed with HIV after numerous visits to the hospital over many months, it was only the beginning of the fight.

Her husband left her, leaving her to look after their child on her own. She fought for her son and his rights, for justice. She went to court, attended rallies, wrote letters, worked with other like-minded people and helped other women in the same situation.

For the past six years, Ms Toktonalieva has channelled that campaigning zeal into working as a peer consultant in a multidisciplinary team in a family medical centre in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, helping people living with HIV to get services, providing support and motivating them to adhere to their HIV treatment. There are 10 multidisciplinary HIV teams in the country, which were formed by UNAIDS in 2013; they all include a specialist in infectious diseases or a family doctor, a nurse and peer consultants.

The peer consultants come from the same environments and backgrounds as the people who they work with and have faced similar problems. They may be people who are living with HIV or people who have been affected by HIV. They have decided to act, helping themselves and others, often serving as a bridge between the medical workers and people living with HIV.

“Working as a peer consultant has given me an opportunity to help people to overcome their problems, many of which I have come across myself in the past,” said Ms Toktonalieva.

The peer consultants work with the medical staff, directing, prompting, helping, talking and listening. They are trained to be non-judgemental and help people who have recently been diagnosed as HIV-positive to accept their status and to learn to live with the virus.

The role of the peer consultants is being expanded by the COVID-19 pandemic. From the very beginning of the pandemic they were in contact with people living with HIV, delivering medicine to people’s homes so they could stay on treatment during the lockdown, distributing food packages and providing psychological support.

Another peer consultant, Kalmurza Asamidinov, who works in Kyzyl-Kiya, said, “My work brings good, but I can’t say that everything works out perfectly. We work with different people. Some need to be persuaded to adhere to their HIV treatment because they don’t believe in the treatment, while others are tired of taking antiretroviral therapy—we have to find a different approach for everyone. People are increasingly in need of simple human communication. Many clients miss mutual help and the support groups, which we cannot provide during the COVID-19 lockdown.”

The peer consultants working in the 10 multidisciplinary teams each have a different story to tell. Mannap Absamov, one of the peers in the multidisciplinary team in Osh, said, “Initially it was difficult. We were not able to understand the medical staff, and they could not understand us. But slowly we found points of contact. The main thing is that almost simultaneously, both on our side and the doctors’ side, there became a clear understanding that we all have one goal. It is important that their patient and our client go to the medical facility and start getting treatment.”

Both during COVID-19 and after, one thing is certain—peer consultants will continue to play a vital role in bringing HIV services to people living with HIV in Kyrgyzstan.

Our work

Region/country

Related

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025

Feature Story

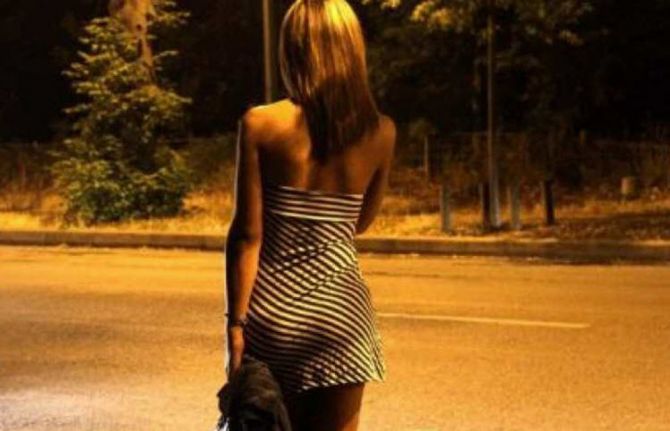

Targeting sex workers is not the answer

08 June 2020

08 June 2020 08 June 2020When the Government of Cameroon ordered everyone to stay at home as part of the COVID-19 response, Marie-Jeanne Oumarou (not her real name) rushed to buy groceries and to gather her three children and move them the countryside.

With her children in safe hands, she hoped she could still work.

“I didn’t realize how hard it would be during confinement,” she said. “It doesn’t make sense for us sex workers.”

Ms Oumarou has learned the ins and outs of the couloirs—the avenues of small hotels where sex workers work—in Cameroon’s capital city, Yaoundé, over the past 10 years. Abandoned with her young children, she became a sex worker in 2010. She has grown to know the various older women, former sex workers themselves, who she pays to access safe places to work. COVID-19 changed her life overnight, though.

“Hotels closed, clients were rare, the police constantly around, I cannot survive,” she said.

Denise Ngatchou, Executive Director of Horizons Femmes, a nongovernmental organization that helps vulnerable women, said she was shocked to see how sex workers suddenly became a target.

“Police arrested and held women, disclosing zero information,” she said. “We felt powerless because the government had the upper hand with all the COVID-19 measures.”

Rosalie Pasma, a manager at one of the Horizons Femmes drop-in health centres, shrugged her shoulders in agreement during a Skype interview.

“Everything became much more complicated during COVID-19,” she said. “From women missing health check-ups because of transport issues to our legal expert not being able to access the police stations to defend arrested female sex workers, we felt the confinement in more ways than one.”

Ms Ngatchou piped in, saying that there was no reason to give up. Horizons Femmes vowed to stay open. A skeletal staff with condensed hours still provided HIV testing and other services by respecting preventive measures.

“People told us to stop all our on-the-ground awareness visits, but we held on as long as we could, giving coronavirus tips to women so they knew of the potential dangers,” she said.

They also kept handing out masks and started a crowdfunding project to purchase more protective gear. What really bothers Ms Ngatchou is how so many things happened before their eyes and they could do so little.

“Easing laws against sex work and ending arbitrary arrests of sex workers would really make an impact,” she said.

In the end, she believes that chastising sex workers only worsens the situation.

“Don’t you think that if sex workers hide they are more likely to work and infect themselves or become infected than if there was an infrastructure to help them?” she asked.

Reflecting on what she said, she added that this applies to COVID-19 as well as HIV.

In early April, UNAIDS and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects sounded the alarm on the particular hardships and concerns facing sex workers globally. They called for countries to ensure the respect, protection and fulfilment of sex workers’ human rights.

“Authorities have got to understand that we are not promoting sex work, we are promoting good health,” Ms Ngatchou said. “That’s the priority.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

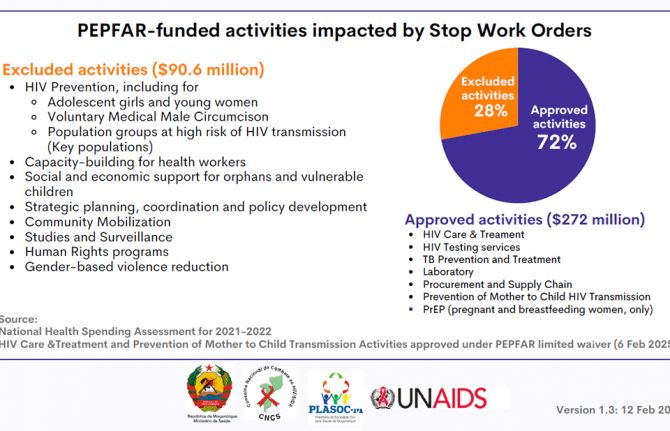

Mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on key populations

04 June 2020

04 June 2020 04 June 2020The COVID-19 pandemic has affected everyone, including key populations at higher risk of HIV. And the gains made against other infectious diseases, including HIV, are at risk of being reversed as a result of disruptions caused by COVID-19. This is the background to a new report published by FHI 360, in collaboration with UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO), which gives advice on how to minimize the impacts of COVID-19 on key populations.

“With a focus on key populations, this guidance complements ongoing efforts to sustain access to HIV prevention services and commodities, sexual health and family planning services, prevention of gender-based violence and HIV counselling, testing and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Paula Munderi, Coordinator of the Global HIV Prevention Coalition at UNAIDS. “Preserving essential HIV services for key populations and promoting the safety and well-being of staff and community members during the COVID-19 pandemic is vital to maintaining the hard-fought gains of the AIDS response.”

With practical guidance on how to support the continuation of HIV services for people living with HIV and key populations, the report is aimed at helping the implementers of programmes to carry on their work.

“Key populations are particularly vulnerable to HIV service interruptions and additional harm during the COVID-19 pandemic. We urgently require rights-based solutions that maintain or increase key populations’ access to HIV services while minimizing potential exposure to COVID-19 and promoting individuals’ safety. These must support physical distancing and decongestion of health facilities, but in ways that respond to the current realities of key populations,” said Rose Wilcher, from FHI 360.

The report gives practical suggestions in three main areas.

The first is on protecting providers and community members from COVID-19. HIV services can only continue to be provided during the COVID-19 pandemic if steps are taken to prevent coronavirus infection among programme staff, providers and beneficiaries. Links to COVID-19-related screening and care, and services to support the mental well-being of providers and beneficiaries, can also be given as part of HIV services.

The second area is supporting safe and sustained access to HIV services and commodities. HIV programmes can integrate physical distancing measures, offer virtual consultations and give multimonth dispensing of HIV medicines. Physical peer outreach should be continued where possible.

Monitoring service continuity and improving outcomes is the third area covered by the report. Since there are likely to be service disruptions, HIV programmes will need to adjust their monitoring and evaluation systems in order to allow for regular assessments of continued HIV service delivery and of the impact of COVID-19 on HIV programmes and their beneficiaries. This may require setting up strategic information systems that use physical distancing measures such as virtual data collection and reporting tools.

“The COVID-19 pandemic shouldn’t be used as an excuse to slow momentum in the global response to HIV among key populations. Instead, the pandemic is a time to draw lessons from our work to end AIDS. It is also an opportunity to provide relief to health systems overstretched by COVID-19 by fully funding community-based organizations led by gay and bisexual men, people who use drugs, sex workers and transgender people to ensure improved access to HIV services for key populations,” said George Ayala, Executive Officer of MPact.

“It remains critical to ensure access to HIV prevention, testing and treatment services during COVID-19 and sustain access to life-saving services. This document provides practical guidance and know-how on maintaining essential health services for key populations in these challenging times,” said Annette Verster, the technical lead on key populations at the WHO Department of HIV, Hepatitis and STIs.

The report was developed by FHI 360 as part of the Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (EpiC) project, which is supported by USAID and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. UNAIDS, WHO, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and partners gave inputs and advice.

Related resources

FHI 360: Five strategies for preserving key population-focused HIV programmes in the era of COVID-19

Global HIV Prevention Coalition

Rights in the time of COVID-19 — Lessons from HIV for an effective, community-led response

Lessons from HIV prevention for preventing COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries

Condoms and lubricants in the time of COVID-19

Maintaining and prioritizing HIV prevention services in the time of COVID-19

Our work

Related

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

Multisectoral resilience to funding cuts in Guatemala

22 December 2025

Feature Story

Lessons learned from HIV for COVID-19 in Senegal

03 June 2020

03 June 2020 03 June 2020Forty years of responding to the HIV epidemic has provided considerable experience on the importance of a human rights-based approach to all epidemics. UNAIDS spoke to Abdoulaye Ka, who is responsible for human rights issues at the Senegal National AIDS Control Council (known as the CNLS in the country), about the lessons that the CNLS has learned from the response against HIV that can be applied to the fight against COVID-19.

How is Senegal addressing stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The experience of the fight against stigma and discrimination related to HIV services has enabled the CNLS to draw the attention of the national COVID-19 management committee and public opinion to the importance of developing communication materials adapted to specific communities. The involvement of affected communities in the definition, implementation and follow-up of COVID-19 programmes has helped to reduce stigma around the disease.

The CNLS Executive Secretary has made several broadcasts to explain the importance of simplifying messages for communities, including to help them develop their own community responses.

The psychosocial care unit in Dakar is also being supported by the CNLS to draw lessons from the experience of HIV and stigma and discrimination in its work against COVID-19.

What measures are being taken to deal with the socioeconomic consequences of COVID-19 in Senegal?

To respond to the socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 on individuals and households, Senegal has deployed an economic and social resilience programme and has earmarked a budget of 1 trillion West African francs (about US$ 1.7 billion) to support the economic sectors most affected by the crisis and to provide food aid to the most vulnerable. A total of 59 billion west African francs (about US$ 100 million) has been earmarked to buy food for one million eligible households.

In particular, the CNLS is partnering with UN Women to increase the resilience of women living with HIV through the provision of food and hygiene kits.

How is the response to COVID-19 in Senegal responding to the specific needs of people living with HIV?

To respond to the needs identified by the national network of people living with HIV, the country is moving to multimonth dispensing of antiretroviral medicines, in accordance with the guidance of the World Health Organization. We are collaborating with service providers and communities in assessing needs in order to avoid stock-outs.

The CNLS has also set up a free telephone hotline for people living with HIV at the Antiretroviral Therapy Treatment Centre of Dakar. It has also set up a WhatsApp network for all antiretroviral therapy care site managers and gives them recommendations on how to adapt the provision of care for people living with HIV, including proceeding with the delivery of at least three months of HIV treatment.

What is the role of community-based organizations today?

Community-based organizations and networks have long been critical to the AIDS response because of their central role in raising awareness, informing, dispelling myths and misinformation and providing services to marginalized and vulnerable populations.

Now more than ever, community actors need to be supported to innovate and be recognized as providers of essential services for HIV and COVID-19.

Community service providers have innovated quickly in the context of COVID-19 in Senegal using appointment systems to prevent too many people being accommodated at the same time in an institution and holding educational sessions virtually.

The CNLS is currently providing logistical support to people living with HIV for the community-based distribution of antiretroviral medicines.

The right to information is a constitutional right in Senegal. What is the role of information in preventing and protecting against epidemics?

The CNLS very quickly developed messages, press releases and banners on social media to draw attention to the preventive steps to be taken against COVID-19, especially for people living with HIV. We also informed people living with HIV in real time regarding the evolving knowledge about HIV and COVID-19.

Information was developed to be expressed in simple terms and to prevent false/fake news that can undermine the use of health services, including vaccination services, that are useful to preserve the health of people, in particular children living with HIV.

Our work

Region/country

Documents

Strategic considerations for mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on key-population-focused HIV programs

04 June 2020

This strategy is intended to support KP-focused HIV programs mitigate the impact of COVID-19. Developed for KP-focused HIV programs implemented or supported by FHI 360 in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa, it may be used and adapted more broadly. Mitigation strategies refer to efforts to reduce exposure to and impact of COVID-19 on HIV program beneficiaries and staff and safely maintain HIV services within KP-focused HIV programs. Not included herein are strategies for responding to COVID-19 directly. This is a living document that will be updated frequently to reflect the rapidly changing context of COVID-19 and its impact on KP members, staff, and programs.

Feature Story

Mobilizing COVID-19 relief for transgender sex workers in Guyana and Suriname

02 June 2020

02 June 2020 02 June 2020Twinkle Paule, a transgender activist, migrated from Guyana to the United States of America two years ago. As the COVID-19 crisis deepened, she thought of her “sisters” back home and in neighbouring Suriname. For many of them, sex work is the only option for survival. She knew that the curfew would starve them of an income. And she was worried that some might wind up in trouble with the law if they felt forced to work at night.

After making contact with people on the ground, her concerns were confirmed. She made a personal donation, but knew it was not nearly enough.

“Being somebody who came from those same streets, I knew we had to mobilize to take care of our community. I know about lying down at home and owing a landlord … about getting kicked out because you can’t afford to pay rent,” Ms Paule said.

She collaborated with New York activists Cora Colt and Ceyenne Doroshow, founder of Gays and Lesbians in a Transgender Society (GLITS Inc), to start a GoFundMe campaign. After launching on 12 May they’ve already raised enough money to cover rent subsidies for one month for six transgender sex workers. The money has been forwarded to Guyana Trans United (GTU), the organization for which she worked as a peer educator when in 2015 she left sex work behind.

That she can now use her position of influence to mobilize emergency relief is itself a stunning success. When she migrated, she’d felt herself tottering on the brink of suicide. The emotional weight of exclusion and injustice was bearing down.

One successful asylum claim later, she’s now a full-time communications student at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. She completed her high-school education last year—something she hadn’t been able to do in Guyana. While studying she worked as an outreach officer for GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis).

She seamlessly slipped into advocacy mode, addressing the city council last year about repealing New York State Penal Law § 240.37, a loitering law that is used to target transgender women. She immediately recognized that this was from the same tradition as the vagrancy laws she’d first been victimized by, and later fought against, in Guyana.

Ms Paule is acutely aware of how much her life prospects have changed due to migration.

“It just shows the difference it makes if somebody is given opportunities and the right tools to make other decisions in life. It showed me what I was lacking was adequate resources and the ability to go into an environment without having to worry about discrimination and violence. I am not saying everything is perfect here, but I don’t face the same level of injustice on a daily basis. I was able to access hormone therapy. And to me the most important thing,” she reflected, “is that I was able to go back to school.”

Her mother died when she was a child. Her father moved on with a new family. She was left in the care of his relatives. There wasn’t always enough money for her education. Some weekends she cleaned a church to earn some cash.

But poverty wasn’t the only challenge. Since she was very small she remembered feeling different. She did not have a label for what she felt, but instinctively knew it would not be accepted. At school she strained to stay under the radar. One day her heart skipped when a classmate said she sounded like an “antiman”—a Guyanese derogatory term for a gay person.

Over the years she repeatedly overheard adults in the household agreeing that she should be put out if she turned out to be gay. At 16 years old it happened. A relative spotted her “dancing like a girl” at a party. Now she was homeless.

Ms Paule sought refuge with other transgender women and, like them, used sex work to survive. The burgeoning regional movement to address the needs of vulnerable and marginalized communities had an impact on her life. From the newly formed Guyana Sex Work Coalition she learned about safer sex and accessed safer sex commodities. When some of her peers started going to conferences they found out for the first time that there was a word for their experience. They weren’t “antimen”. They were transgender.

But life on the street was brutal. If someone was robbed or raped they could not report the crime.

“The police tell you plain, “Why are you coming here when you know prostitution and buggery are against the law?”,” she remembered.

She said sometimes rogue police officers threatened to charge them and extort money from them.

Once the police locked up her and other transgender women together with men at the police station and threw condoms into the cell—a green light to the other detainees. She was a teenager at the time.

She accompanied a friend to the police station to make a domestic violence report one day. Instead a policeman told her, “You are involved in buggery. I am locking you up.”

In 2014, a group of them were arrested for sex work in Suriname. Among other indignities, a prison guard forced them to disrobe and squat outside their cell, in the presence of other detainees.

Seven years ago, one of her friends was killed, her body was thrown behind a church. There was no investigation.

Trauma after trauma. It takes its toll.

Even when nothing happens, there is lingering fear. Will I be put out the taxi? Will people insult me on the street? Will I be mistreated because of what I’m wearing?

“The girls take it like it’s their fault,” Ms Paule reflected. “Even in my personal experience I felt people had a right to do me things because I was not behaving in accordance with societal norms.”

Even as she stepped into advocacy, she didn’t feel whole. She attempted suicide once and began having a drink or smoke before turning up to work. Two years ago she was unravelling. Now she’s rallying forces in the service of her community.

Ms Paule credits the work of organizations like the Society against Sexual Orientation Discrimination and GTU for advancing the dialogue around inclusion in Guyana.

“What is still missing is safety and equity for the community,” she insisted. “We need a state response to say, “These people should be taken care of”. The trans community has no jobs, we are bullied out of school, we suffer police brutality. These things are wrong. We need more robust action from our elected officials.”

Our work

Related

Feature Story

Caribbean community organizations call for decisive action to end homophobic abuse and cyberbullying

29 May 2020

29 May 2020 29 May 2020Ulysease Roca Terry was a gay Belizean fashion designer living with HIV. He had recently lost his mother and was coping with depression. Even without a new pandemic, it was a difficult time.

He was arrested for breaching COVID-19 curfew laws in April. While in custody he suffered homophobic slurs and bullying by a police officer. A video of the abuse was posted to social media. He also claimed that he was physically attacked while detained. Days later he died.

This month in the Bahamas, a video circulated on social media of a gender non-conforming woman being beaten by three men hurling homophobic slurs. One man smashed a piece of wood onto her head. Others slapped and punched her. As the video circulated online, some made fun of the victim.

While countries in the Caribbean focus on combatting COVID-19, community organizations have been raising their voices against the casual verbal, physical and emotional abuse that is a feature of life in the region for far too many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people. And they are sounding an alarm that this cruelty is increasingly playing out online.

Caleb Orozco of the United Belize Advocacy Movement (UNIBAM) spoke about Mr Roca Terry’s case with a mix of sorrow and defiance. Mr Orozco is used to tough battles. He was the litigant who successfully challenged Belize’s law banning consensual sex between same-sex partners in 2016.

“The police cannot erode public confidence in its law enforcement role by showing disregard for the dignity and rights of individuals who are members of the most vulnerable groups: those with mental health challenges, those living with HIV and those with different sexual orientation,” Mr Orozco said. “It is the responsibility of the police department to enforce the curfew in a manner that is reasonable. Mocking people does not help to build public confidence that the police are there to protect ordinary citizens.”

UNIBAM is calling for a transparent investigation, a review of the autopsy report and action to improve how the police treat members of vulnerable and marginalized communities, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 restrictions.

In Belize, a national dialogue is under way around a proposed Equal Opportunities Bill. A UNAIDS public opinion survey conducted in 2013 found that Belize was among the more tolerant Caribbean countries, with 75% of respondents agreeing that people should not be treated differently based on their sexual orientation. But this incident is a reminder that notwithstanding strides made in social attitudes and the law, pervasive challenges remain around prejudice and the abuse of power.

The Bahamas Organization of LGBTI Affairs has called the attack circulated on social media a hate crime and demanded that the perpetrators be prosecuted.

“Around the world, this kind of hate crime—the targeting of a person with extreme violence because of who they are—is denounced as among the most reprehensible modes of human conduct imaginable,” Rights Bahamas said.

Alexus D’Marco, Executive Director of the Bahamas Organization of LGBTI Affairs, insisted that there must be a broader dialogue and action to address social attitudes.

“What does it say about us as a people that so many consider this a source of humour and entertainment? What are we to think when so many of the culprits are fellow women, who should be standing together in solidarity to oppose the many injustices faced in common as members of an oppressed gender in this society?” Ms D’Marco demanded.

The Bahamas is the only Caribbean country to have decriminalized sex between consenting adults of the same sex by an act of parliament. Still, lots more work needs to be done to bring social attitudes in line with the law. Advocates insist that hate crime legislation must urgently be enacted and enforced.

In both the Bahamas and Belize, state entities have joined civil society to denounce the attacks. The National AIDS Commission, the Office of the Special Envoy for Women and Children and the Ministry of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation have called for Mr Roca Terry’s case to be thoroughly investigated. In the Bahamas, the Ministry of Social Services and Urban Development called for a swift prosecution to signal zero tolerance by the government and society for gender-based violence.

“Alongside legislative reform and key population programmes, we must continue the social dialogue and law enforcement to create more peaceful and inclusive Caribbean societies for all,” said James Guwani, UNAIDS Director for the Caribbean.

Related

Feature Story

“We cannot provide only HIV services while sex workers are hungry”: Thai community organization steps in

01 June 2020

01 June 2020 01 June 2020When the Thai government ordered the closure of entertainment venues in the country in March, it didn’t just signal an end to pulsating music and rounds of drinks shared with friends. It also signalled the start of difficult times for an estimated 145 000 sex workers living in Thailand.

Initially, Service Workers in Groups (SWING), a Thai national organization providing HIV services and advocating for sex workers’ rights, received requests from sex workers for the most basic of needs—food. As requests began flooding in, it became clear that without a source of income many sex workers were unable to cover the cost of daily expenses, housing and medicine.

“When the COVID-19 outbreak began, nobody was talking about sex workers, and no measures were in place to help them,” said Surang Janyam, Director of SWING.

Spurred by growing concerns about how the outbreak has impacted the lives of sex workers, SWING, in collaboration with Planned Parenthood Association Thailand and Dannok Health and Development Community Volunteers, with support from UNAIDS, launched a community-led rapid assessment of 255 sex workers from Bangkok, Pattaya and Dannok and community-based organizations throughout the country.

The outbreak has had a severe socioeconomic impact on the lives of sex workers, further exacerbated by the lack of social protection measures. According to the findings from the rapid assessment, 91% of respondents became unemployed or lost their source of income following the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. Three quarters of the respondents could not make enough money to cover daily expenses and 66% could no longer cover the cost of housing.

Ms Janyam spoke about the difficulties faced by sex workers and how the priorities for SWING’s work have shifted. “As a sex worker-led organization, we cannot provide only HIV services while sex workers are hungry and lack the basic needs to survive,” she said. She explained that many of the sex workers expressed that they were not eligible for the government assistance of 5000 baht. Answering the call for help, SWING staff have taken to the streets to raise donations and deliver food to sex workers in their network.

Widespread coverage in the media and on personal blogs has catalysed a public conversation about the lack of social protections for sex workers. Ms Janyam also points to donations from local businesses and visits from younger people wanting to help as promising signs of how wider audiences are becoming more engaged on the topic of supporting sex workers in their communities.

The COVID-19 outbreak has also contributed to new challenges for HIV prevention. Fears of COVID-19 have deterred people from visiting clinics to be tested for HIV. Additionally, the rapid assessment findings revealed that almost half of the sex workers surveyed had difficulty accessing sexually transmitted infection screenings. In response to those observations, SWING partnered with a hospital capable of conducting COVID-19 testing, thereby drawing in sex workers interested in being tested for COVID-19 and creating an opportunity to counsel them about HIV tests. These changes in practice show possible synergies in prevention measures for both COVID-19 and HIV prevention and treatment.

“The results from the rapid assessment have proven to be a strong tool for advocacy and decision-making. Stakeholders of the AIDS response have collectively identified and started to implement priority actions as an immediate response to the needs of sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Patchara Benjarattanaporn, UNAIDS Country Director for Thailand.

Ms Janyam reflects on what this will mean for SWING’s work and recalls the ways in which sex workers were not afforded the same social safeguards as others—they were forgotten. “We must transform ourselves. Community-led organizations must apply a holistic and comprehensive approach, providing immediate basic needs, integrating a package of prevention for both COVID-19 and HIV health services, as well as mental health support for sex workers,” she said.

She affirms that SWING and other charitable groups will continue to seek donations and provide basic provisions for sex workers, recognizing that the need for assistance will remain long after the situation eases, long after the bars and restaurants have reopened.