Feature Story

“My biggest concern is to get my antiretroviral medicines”: HIV and COVID-19 in Latin America

28 May 2020

28 May 2020 28 May 2020Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Marcela Alcina, of the Latin American and the Caribbean Movement of Positive Women (MLCM+), has received more than 20 calls a day asking for help, either for food, medicine or advice on how to cope with the lockdown.

Yesenia Rodriguez (not her real name) made one of those calls. A Colombian by birth, she lived for more than 24 years in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, but owing to the humanitarian crisis in that country, she had to return to Cali, Colombia, six months ago to access her treatment for HIV.

“There’s eight of us: my four children, my husband, my two grandchildren and me,” she said.

Ms Rodriguez does not have a job and needs help to feed her family and to access antiretroviral medicine. “I came back to Cali only to find myself living another crisis. My biggest concern is to get my antiretroviral medicines, but I don’t have access to health care in Colombia,” she said. “It’s been extremely tough for me and my partner, since we’re both living with HIV. My children and my husband are unemployed. Kids can’t put up with hunger the way we grown-ups do.”

Ms Rodriguez was put in contact with Yani Valencia of the Lila Mujeres Organization, part of the MLCM+ network. She was given a food package for her and her family, and she is being put in contact with someone who is able to ensure that she can access antiretroviral therapy. “I was about to pass out when they brought me these groceries, I was extremely happy.”

UNAIDS is recommending that, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, people living with HIV keep necessary medical supplies on hand. The World Health Organization HIV treatment guidelines now recommend multimonth dispensing of three months or more of HIV medicines for most people at routine visits. However, according to a recent survey carried out by UNAIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean on the community needs of people living with HIV in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, only one in 10 people reported having a three-month supply of antiretroviral therapy.

“We have met people who have no access to health care. A colleague of ours in Colombia borrowed a neighbour’s motorcycle to distribute medicines. We notice communities are overlooked quite often, but we must be a part of the answer. We couldn’t wait any longer, we had to do something,” said Ms Alcina.

Communities have played and continue to play a fundamental role in the AIDS response at the local, national and international levels. And now communities are playing a major role in the fight against COVID-19. MLCM+ has developed a network of 850 volunteers working in 17 countries in the region whose aim is to spread solidarity during the COVID-19 pandemic, keeping the focus on people living with HIV.

“We are distributing food and cleaning products, we are making masks that will later be distributed along with antiretroviral therapy, we are teaching people some prevention methods, we are giving condoms away and helping people find shelter in domestic violence situations,” said Ms Alcina.

MLCM+ is working across the region with UNAIDS, UN Women, the United Nations Population Fund and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, all of which are offering technical or financial support.

“UNAIDS provides us with resources, specialists and training webinars. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, on the other hand, helps us financially. That way, we are putting together a mechanism that intends to support the government’s actions, not replace them,” said Ms Alcina.

“We see how inequalities have become more evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inequality, and especially gender inequality, is exacerbated in times of crisis. Women living with HIV must be in the centre of the responses to both HIV and COVID-19, and must not be left behind,” said César Núñez, Director of the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Related links

Region/country

Feature Story

Pia Wurtzbach on how she is helping the response to COVID-19

27 May 2020

27 May 2020 27 May 2020Pia Wurtzbach, Miss Universe 2015 and UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Asia and the Pacific, has long been an advocate for the AIDS response in the Philippines and the rest of the region. Recently, however, her work has taken in support for the COVID-19 response, including starting a fundraising effort with the aim of distributing 25 000 face masks to hospitals in Manila and supporting social media campaigns on preventing both COVID-19 and HIV.

UNAIDS spoke to Ms Wurtzbach about her work during this challenging time.

How did you organize the drive to donate face masks to health facilities in Manila?

To begin with, I ordered 5000 masks with my own money to identify an affordable and reputable supplier. I found one and ordered the masks and then delivered them to four hospitals. Once I was ready and confident, I started the fundraising drive, reaching out to the private sector in the Philippines and my network of contacts. So far, I have been able to donate masks to 30 hospitals in Metro Manila. We wanted to deliver masks to other hospitals outside the capital city, but because of the lockdown this hasn’t been possible yet. In addition, I have been able to donate meals to an intensive care unit in one of the hospitals in Metro Manila. Nurses and doctors working in the unit have been living in the hospital and do not go home. With the donations, I feel I am supporting them.

How do you continue to support the response to HIV in your role as a UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador?

Every day I am in contact with LoveYourself, the civil society organization I volunteer for in the Philippines, to update each other on what is going on and to monitor the needs of people living with HIV. I post information on my social media platforms about HIV and COVID-19 prevention and how to stay healthy. I keep my followers informed of the services provided by LoveYourself to support people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as home delivery of antiretroviral medicines.

What questions do you receive from people living with HIV or from key populations in relation to HIV and COVID-19?

The most popular questions are how to access medicines and whether there are going to be enough refills. It is great that organizations like LoveYourself in the Philippines help people living with HIV to access their medicines. I am really impressed with Vinn (Ronivin Garcia Pagtakhan), the founder of LoveYourself, because he has been using his own car driving around everywhere delivering medicines to people’s homes. He is like a modern-day superhero.

How have you kept motivated to continue your work in these trying times?

I am so blessed because I have a lot of friends in the industry who are nurses too. You will be surprised that my makeup artist is a registered nurse, and there are photographers who are registered nurses. In the Philippines, there are so many nurses that somehow end up doing other careers, but they are all still in the medical field and they know people in the medical field. I hear so many stories from them, and I know these are real stories about what the hospitals are like and about their environment.

Hearing their stories made me feel like I needed to do something. I feel very fortunate that I am able to stay at home. So, I thought to myself, what can I do to make myself useful? This is why I started my donation drive. The medical staff sent me messages of appreciation and even a video of them saying thank you. When I see that the people on the frontline take the time to say thank you, I want to help even more.

The fundraising campaign gave me a sense of mission and purpose. That is what I tell people. If you are at home and you have followers on Instagram, or maybe you are an influencer or a celebrity, or maybe you are just popular in school, use it! Now is the time! We cannot just sit and wait for this to be over. The solution has to come from us.

What do you miss most from your life before the COVID-19 pandemic?

I feel like I took the little things for granted. I took for granted the little commute going to work, I took for granted the travelling, I took for granted how busy I was with my work. I remember before the lockdown I got burnout because I was doing so much work. I was not getting any free days or any weekends—I was working from Monday to Sunday. And I said to myself that I needed some time alone. And then suddenly this all happened. I am just taking the time now to reflect and think about what is really important to me.

I miss everything. I miss being able to walk outside, I miss the traffic, I miss seeing other people. I feel that the lockdown is really giving us time to think about what is important for us. I feel like when we get out of the quarantine and self-isolation, we will know what to prioritize.

How do you spend your leisure now being at home in quarantine?

You know, the good thing about the lockdown is that I have more time for myself. Every day I go to the roof deck of my building to work out, so I bring my yoga mat up there and spend a few hours trying to get some sunlight and exercise. I have a routine every day, and I feel like if you have a little routine, you will feel like your days have direction. When I wake up in the morning, I try to get emails done and some work done. In the afternoon, I will work out. And at night I can bake, or watch television, watch Netflix. So, it is work, sunlight and then “me time”. I feel like this is a nice balance, because it is making yourself productive and taking care of yourself.

What are your next steps after you reach the target of donating 25 000 masks?

It is not set in stone, but my team and I are thinking of ways to help people who need economic support and donate them food. In addition, I would like to focus on social media messages on mental health to give people tips on how to control or manage their anxiety. People are at home and on their phones, so maybe they can read something that will help them manage their stress.

Video

Region/country

- Asia and Pacific

- Australia

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Brunei Darussalam

- Cambodia

- China

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea

- Federated States of Micronesia

- Fiji

- India

- Indonesia

- Islamic Republic of Iran

- Japan

- Kiribati

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Marshall Islands

- Mongolia

- Myanmar

- Nauru

- Nepal

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Palau

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Republic of Korea

- Singapore

- Solomon Islands

- Sri Lanka

- Thailand

- Timor-Leste

- Tonga

- Tuvalu

- Vanuatu

- Viet Nam

- Samoa

Feature Story

“When people are asked to isolate themselves, we also need to make sure that they have food and medicine”

26 May 2020

26 May 2020 26 May 2020When non-essential shops and markets were closed in Senegal in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in the country, and movement between regions in the country was stopped, many people working in the informal sector, including people living with HIV, lost their income. Hunger was dangerously near for many.

Within days, the National Network of Associations of People Living with HIV in Senegal (RNP+) mobilized, setting out to its members the food aid options available from the government for 1 million eligible households and offering advice on how people should prevent themselves from becoming infected by the coronavirus.

“When people are asked to isolate themselves, we also need to make sure they have food and medicine. Communities of people living with HIV help each other to take care of themselves, isolate themselves, access medication when needed and take care of each other’s families,” said Soukèye Ndiaye, the Chairperson of RNP+.

Community leaders and nongovernmental organizations are playing an active role in Senegal in giving out clear and accurate information in order to avoid panic and in combating stigma and discrimination, against both HIV and COVID-19. RNP+ is monitoring the response to COVID-19 as it unfolds, mapping how COVID-19 is affecting the most vulnerable and bringing urgent issues to the attention of the government and service providers.

Advocacy with the National Alliance of Communities for Health and ENDA Santé enabled RNP+ to distributed more than 200 food and hygiene packs to the poorest families of people living with HIV. The UNAIDS country office in the country has stepped in by providing a grant to ensure that the One Family–One Kit programme continues to distribute aid to the people most in need.

RNP+ is also advocating for funding for people living with HIV to help them to travel to health centres, since transport costs have increased, and for financial support for the scaling up of the work of community health workers, who are active in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring continuity of HIV treatment by distributing multimonth supplies of antiretroviral therapy is vital. Although RNP+ has called on the government for all people living with HIV to get multimonth refills, weaknesses in the supply chain, including inadequate assessments of the needs at some clinics for supplies of antiretroviral therapy and irregular supplies centrally, has meant that not all people who need such supplies are getting them. UNAIDS is supporting the government in tracking orders of antiretroviral medicines and in strengthening the supply chain.

The role of communities, especially communities of the most vulnerable, is critical in the time of COVID-19. “The history of the HIV epidemic has made it clear that the response to an epidemic is only effective if affected communities are fully involved in the response, from its planning through to its implementation and monitoring. Only then can a response be based on the realities and needs of all,” said Demba Kona, the UNAIDS Country Director for Senegal.

Region/country

Related

Opinion

We will not defeat COVID-19 without including Africa in the global response

25 May 2020

25 May 2020 25 May 2020This article was first published on 19 May 2020 here

In much of the global COVID-19 conversation, Africa is barely mentioned. But the risks which the COVID-19 crisis brings are even greater in Africa than elsewhere – and those risks will be compounded if Africa is marginalized in the global response. Beating COVID-19 in Africa, in turn, is essential for beating it worldwide. African leadership and global solidarity are both essential to overcoming the COVID-19 crisis in Africa, and Africa’s citizens demand nothing less.

Economic and social determinants of ill-health are strong predictors of the likelihood of dying from COVID-19. The greatest risk will be for poor people in poor countries who have a much higher burden of existing illness, and of whom hundreds of millions are malnourished or immunocompromised. While Africa does have vital experience of managing epidemics, it also has health systems which are largely under-resourced and which are still often inaccessible to the poor, and not up to the job of beating COVID-19.

Beating back COVID-19 in Africa is possible, but not under business as usual. We need urgently to accelerate access to testing; ensure equal access to equipment to protect frontline medical workers and treat the sick; ensure that health systems are adequately funded; agree globally that any COVID-19 vaccine is free for all; and ensure that the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis are mitigated through large-scale social protection measures and sustainable economic development which reduces inequality.

The African Union, through its Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, is taking a strong lead in the response to the epidemic. It has created a new partnership as part of the Africa Joint Continental Strategy for the COVID-19 response, the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing (PACT), which has been fully endorsed by the Bureau of African Union Heads of State and Governments. UNAIDS is proud to be the first to sign up for this partnership, which aims to close the gap in testing by supporting the efforts of African countries to rapidly scale up their capacity to test and trace. As we have seen in other regions of the world this is crucial to reduce the number of infections and deaths. PACT also calls for the rapid establishment of an Africa CDC-led system for pool procurement of diagnostics and other COVID-19-related response commodities.

The good news is that countries are stepping up: at the beginning of May, South Africa had conducted more than 300,000 tests, with Ghana on more than 100,000. They have done so in part by leveraging the exiting HIV testing infrastructure, and other countries such as Nigeria plan to follow suit. But Africa CDC estimates that Africa needs 10 million tests to respond to the pandemic in the next four months. In addition, the World Health Organization estimates that 100 million face masks and gloves, and up to 25 million respirators, will need to be shipped to African countries every month to respond effectively to COVID-19, at a time when there is a global scramble for supplies.

Worldwide, production of test kits and essential medical supplies must be ramped up and there must be globally coordinated efforts to get the tests and personal protective equipment to the places and people most in need: in Africa that means to our high-density population townships and to our frontline medical staff and community health workers responding to the epidemic. We also need to leverage existing HIV services to boost COVID-19 testing, isolation, contact tracing and treatment capacities.

Now more than ever, African countries need to prioritize investment in essential services. This must include a real commitment to tackle massive corporate tax evasion and ensure that those with the broadest shoulders pay the most tax, including an end to corporate tax exemptions. Now more than ever, also, we need global solidarity to fund a multi-billion-dollar response that includes low and middle-income countries in Africa and the rest of the world. This includes fully funding the United Nations US$2 billion COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan as well as providing grants to support the abolition of user fees for health services. This pandemic has shown that it is in everyone’s interest that people who feel unwell should not check their pocket before they seek help. As the struggle to control an aggressive coronavirus rages on, the case to end-user fees in health immediately has become overwhelming. International financial institutions and private financial actors need to both extend and go beyond the temporary debt suspensions that have recently been announced - Africa’s debt is about 60% of the continent’s gross domestic product which is completely unsustainable. We must free governments to invest in the response and to strengthen publicly funded health care provision underscored by the principle that everyone has the right to health. In responding to COVID-19, we must be on our guard that resources are not diverted away from other health threats such as the HIV epidemic, tuberculosis, or malaria, which are already taking a heavy toll on Africa.

Modelling conducted on behalf of the World Health Organization and UNAIDS has estimated that if efforts are not made to mitigate and overcome interruptions in health services and supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to more than 500000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses, including from tuberculosis, in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020–2021.

There also needs to be prior international agreement that any vaccines and treatments discovered for COVID-19 will be made available to all countries and be free for all. We must not repeat the experience of the HIV epidemic, where medicines remained beyond reach for too long and millions died, while others are still waiting to initiate treatment today.

A strong recovery is key to building the resilient societies capable of withstanding the next unexpected event. Given the interconnectedness between health and livelihoods, all countries will need to strengthen social safety nets to enhance resilience. They will need too to build more sustainable economies, including decent, well-paid jobs for Africa’s young population and recognition for the undervalued and often unpaid care work carried out by women.

If it has taught us anything, this pandemic has shown how interconnected we are as a global community and that, as the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, has said, the world is only as strong as its weakest health system. Any global response to COVID-19 which marginalizes Africa’s citizens would not only be wrong, it would be self-defeating. Moreover, Africa’s citizens would not stand for it. Even in the exceptional constraints of this pandemic, ordinary Africans have been organizing to insist on their rights to healthcare and on their rights to social protection. As Africans, we stand with them in refusing to be sent to the back of the COVID-19 queue.

Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS

John Nkengasong, Director of Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Related

Feature Story

“We are in this together”: Uganda Young Positives respond to COVID-19

25 May 2020

25 May 2020 25 May 2020Kuraish Mubiru wakes up at dawn every day to get refills of antiretroviral therapy from different health facilities before making deliveries to his peers and other members of the community living with HIV. This has been his routine for the past seven weeks.

Mr Mubiru is the Executive Director of Uganda Young Positives (UYP), a community-based organization that brings together young people living with HIV, mainly from the informal sector. With more than 50 000 registered members, UYP focuses on scaling up HIV prevention, care and support services for its members.

When Yoweri Museveni, the President of Uganda, first addressed the nation on 18 March on the global COVID-19 pandemic, among the measures put in place were restrictions on mass gatherings, the closure of most businesses and the cessation of public transport. Since then, people living with HIV and tuberculosis have found it difficult to access their routine medical care or essential medicine refills.

Following the measures, Mr Mubiru started receiving calls from young people whose livelihoods and HIV treatment were dependent on facilities that had been closed. The impact of the restrictions was beginning to be felt. Young people were no longer able to move to their respective health facilities to access care and treatment nor afford a meal.

Although there have been efforts by health centres and civil society organizations to transport antiretroviral medicines closer to the people, a good number, as reported by the community support groups and health centres, have not received their antiretroviral medicines owing to fear of stigma and discrimination by the community and family members.

“This was a trying time for the community and a huge test of our resilience because our peers needed us more than ever,” said Mr Mubiru. “We had to come out of our comfort zone, act and think fast not to lose all our gains in the national HIV response in the wake of COVID-19.”

Mr Mubiru volunteered to support his fellow peers to access HIV treatment using his own car. In the beginning, he used his own resources to fuel his car and purchase food, but he soon ran out of money.

Initially, one of his biggest challenges was being able to fuel his car to continue with the daily refills, but the further tightening of restrictions on private transport meant that Mr Mubiru could not continue with deliveries. Through the support of UNAIDS, the Infectious Disease Institute and the Ministry of Health, he obtained a permit granting him permission to enable him to continue supporting his community.

During one of his routine deliveries, Mr Mubiru’s car was impounded by the police for more than four hours and he was made to wait. It took the involvement of the police leadership to have the car and Mr Mubiru released. On many occasions, he has been stopped by the police, demanding to know where he is going—those delays at times force him to get home past the curfew time of 19:00.

Mr Mubiru’s resolve to support his community is unwavering. He knows that not everybody would be comfortable visiting the nearest health facility for their antiretroviral refills, disclosing the reason to the local authorities for them to be granted movement or have a community organization’s branded car parked outside their home.

“Instances like these propel me to get out of bed every morning. We are still in this together. COVID-19 will end, and life will continue,” he says.

On average, he delivers eight antiretroviral refills per day to his peers. Besides the long distances and hard-to-reach places he has to go to, food is one of the biggest challenges, since hunger compromises people’s adherence to their medication. Stigma and non-disclosure also pose a great challenge for people to access HIV treatment from a nearby facility.

“The COVID-19 outbreak is having a major impact on people living with HIV,” said Karusa Kiragu, UNAIDS Country Director for Uganda. “We must ensure that adherence to HIV treatment is not compromised. This can be achieved through multimonth dispensing of antiretroviral therapy, supported by a strong community-led response,” she said.

More on COVID-19

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

Modelling the extreme—COVID-19 and AIDS-related deaths

25 May 2020

25 May 2020 25 May 2020Kimberly Marsh, a senior adviser on modelling and epidemiology, has worked for UNAIDS for six years. She supports countries in estimating the impact of the HIV epidemic globally and regionally.

Can you tell me more about the latest modelling report that you are a co-author of, which examines the potential for HIV service disruption in times of COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa?

This work looks at potential disruptions in sub-Saharan Africa owing to the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV services that might have an impact on HIV incidence—the number of new HIV infections—and on the number of AIDS-related deaths in excess to those we might have observed if we hadn’t had the COVID-19 pandemic.

We are particularly interested in those question because we know that more than two thirds of all people living with HIV worldwide are living in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s 25.7 million people living with HIV, 1.1 million new HIV infections and around 470 000 deaths from AIDS-related causes in 2018. Among all people living with HIV in the region, 64% of people are on life-saving antiretroviral therapy, which also prevents further new HIV infections.

It is really important that we’re able to ensure they will have access to services. In the models, we looked at service disruptions—a complete disruption of any HIV-related services over a three-month and a six-month period of time. And we looked at the impact after one year and five years. Now remember, these are just scenarios, and extreme ones. We don’t expect this to happen, but it helps us to answer two questions: what HIV-related services are most important to prevent additional deaths and new HIV infections and what might happen if we don’t mitigate or address those disruptions.

From this huge amount of work, what are the two key takeaways?

The modelling work predicted that with a six-month disruption in HIV treatment there could be an excess of 500 000 deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. So, when you look at UNAIDS estimates of AIDS-related deaths over time, that would take us back to about 2008, when we had nearly a million deaths.

There is no doubt about it, HIV treatment is critical. Ensuring that HIV treatment is available to people who need it during the three- to six-month periods is the most important thing that countries can do to prevent excess deaths and HIV incidence. All countries should work to ensure that supply chains are providing them with enough medicines to distribute and that people have sufficient medicines so that they can take them over the coming months.

The second thing to say is that these are projections and that there is still time to ensure that people get the HIV treatment services they need.

Let’s prevent what this model potentially predicts and let’s get HIV medicines to the people who are living with HIV.

What about HIV prevention? Does condom availability have an impact?

The models showed that when you look at prevention services, condom availability impacted the results. I think it is important to say that this is a treatment lesson primarily, but things like access to condoms is really important. We saw around a 20–30% relative increase in HIV incidence over one year if condoms were not available for six months. This is definitely something that we should be focusing on.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the impact on mother-to-child transmission of HIV in these scenarios?

In the scenarios, we looked at the potential for HIV testing services to be disrupted as well as for women to not get medicine to prevent transmission of HIV to their children. And what the various models found was that by removing those medicines—which have had an extremely important impact in terms of reducing new child HIV infections over the past five to 10 years—you could see rises in new child HIV infections in selected countries anywhere up to 162%. It really is critical to maintain prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services.

You have said this was an extreme scenario, not a prophecy, but yet you still believe in modelling?

Models are very important for exploring questions that countries routinely pose to UNAIDS and the World Health Organization in terms of thinking of strategic approaches to responding to HIV in their countries. Models aren’t perfect, but they have a lot to tell us and I think in this instance it really highlights some of the strategies that will be important over the coming months as COVID-19 impacts or potentially impacts sub-Saharan Africa.

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS and civil society helping stranded people living with HIV

22 May 2020

22 May 2020 22 May 2020A day before Deepak Sing (not his real name) planned to return to India, all international travel ground to a halt—he was stuck in Luanda.

Because of his frequent travel, he had extra HIV medicine, but his supplies started to run low.

“I visited more than 10 pharmacies and explored options of delivery of antiretroviral medicines from India to Angola, but without success,” he said.

He decided that reaching out to Indian colleagues would be his best bet.

“I contacted the Humsafar Trust in Mumbai, and they in turn contacted the UNAIDS India office,” he explained.

Bilali Camara, the UNAIDS Country Director for India, immediately followed up with his peer in Angola. The UNAIDS Country Director for Angola, Michel Kouakou, guided Mr Sing towards the national AIDS institute, which organized a conference call with a medical doctor because one of the medicines that Mr Sing took is not yet in use in Angola. The doctor proposed a substitute and in less than 24 hours he picked up his medication. “Due to the change of one medicine, Mr Sing received only a one-month supply, which will be renewed at his discretion,” explained Mr Kouakou, who has helped two other stranded foreigners in the past month.

“I now believe that humanity exists!" Mr Sing said with great relief.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, UNAIDS has helped stranded people to obtain HIV medicine in countries as diverse as Canada, China, Latvia, Myanmar and Ukraine. Mr Camara said that UNAIDS set up a system so that 700 people from India who were living in Myanmar could access their medicine, since they could no longer access it in India because of the COVID-19 lockdown.

Jacek Tyszko, Senior Programme Adviser at UNAIDS’ Geneva headquarters, has never seen anything like this. So far, he has helped 100 people, mostly in eastern Europe, because of his experience in the region.

“Either I connect people to the local AIDS authority or ideally we link them up to civil society, because they usually have readily available treatment,” he explained. Because of demand, some grass-roots organizations have run out of supplies, which meant some readjusting.

“Overall, the response from local partners has been immediate,” Mr Tyszko said. In certain cases, if stranded people could not get treatment locally, UNAIDS helped them to get supplies from the person’s native country.

He cannot believe how people have had to overcome so many hurdles to obtain HIV medicine despite a clear need.

“In times of crisis like COVID-19 or other public emergencies, governments should waive restrictions to make it easier for people to obtain refills and life-saving care, regardless of their legal status, residency or citizenship,” he said.

UNAIDS has been advocating for the right to health and universal health coverage to alleviate problems like this. A better integration of HIV and other health services could help some of the gaps in the AIDS response to be addressed, which will ultimately make it easier for people to access life-saving medicines, care and support.

For now, Mr Tyszko feels that helping people is very satisfying. “It’s been such a boost to do something so concrete with immediate effect,” he said.

Our work

Feature Story

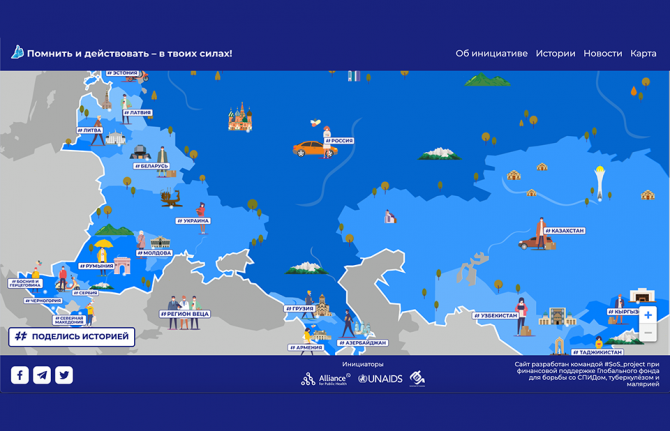

Mapping community responses to COVID-19 and HIV in eastern Europe and central Asia

21 May 2020

21 May 2020 21 May 2020During the COVID-19 crisis, activists and community organizations from across eastern Europe and central Asia are continuing to provide vital HIV prevention, treatment, care and support services.

To map that support, an interactive platform, the Community Initiates Map, has been launched. The website shows how communities are supporting people living with HIV and saving lives during the COVID-19 outbreak in the region, with stories about the services that community organizations are providing. People can learn from the examples of the services developed for key populations and people living with HIV and the impact that they are having on the HIV epidemic and on people’s lives. The map is constantly being updated and people can share their stories on the site.

Vera Brezhneva, UNAIDS Goodwill Ambassador for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, thanked activists for their commitment during the COVID-19 outbreak. “Thank you to every one of you, from all of us. It is in our power to remember and take action. I am with you!” she said.

The experience in eastern Europe and central Asia in the fight against COVID-19 shows that investments made in civil society are good investments. “Communities and nongovernmental organizations have not only come to the forefront of the fight against the new threat, but also in collaboration with medical practitioners and governments continue to provide HIV and tuberculosis services,” said Andrei Klepikov, Executive Director of the Alliance for Public Health.

Nurali Amanzholov, the President of the Central Asian Association of People Living with HIV, said that the coronavirus outbreak and lockdowns had resulted in some people having difficulties in accessing antiretroviral therapy and opioid substitution therapy, and that many people had lost their incomes. “But this situation is also an exam, a test of the strength of our community. And our strength was always in solidarity, the ability to assert our rights, to seek the right solution together,” he said.

Lyubov Vorontsova, of the Central Asian Association of People Living with HIV, said that women living with HIV, especially those in key populations, faced increased gender-based violence and limited access to protection and social services owing to the closure of crisis centres. “We must keep our unity now, so that after the end of the state of emergency, the needs of women remain a priority for the state and civil society,” she said.

“The nearly 40 years of experience in the response to HIV shows that civil society organizations, including communities of people living with HIV, play a crucial role. Today, it is clear that the role of community organizations in emergencies is vital. Countries in the region must recognize those organizations as partners and providers of services for the responses to both HIV and COVID-19,” said Alexander Goliusov, Director, a.i., UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The website was developed by the Alliance for Public Health and the Central Asian Association of People Living with HIV and supported by the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Interactive platform

Learn more

Region/country

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Albania

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Estonia

- Georgia

- Hungary

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Montenegro

- Poland

- Republic of Moldova

- Romania

- Russian Federation

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Tajikistan

- North Macedonia

- Türkiye

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- Uzbekistan

Related

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

Women, HIV, and war: a triple burden

12 September 2025

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

Displacement and HIV: doubly vulnerable in Ukraine

11 August 2025

Opinion

Health: providing free health for all, everywhere

20 May 2020

20 May 2020 20 May 2020By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director — First published in World Economic Forum's Insight Report (May 2020)

Recognizing the public-health catastrophe

As we have seen in wealthier countries, economic and social determinants of ill-health are strong predictors of the likelihood of dying from COVID-19. The greatest risk will be for poor people in poor countries who have a much higher burden of existing illness, and of whom hundreds of millions are malnourished or immunocompromised. For the quarter of the world’s urban population who live in slums, and for many refugees and displaced people, it is not possible to socially distance or to constantly wash hands.

Half the world’s people cannot access essential healthcare even in normal times. While Italy has one doctor for every 243 people, Zambia has one doctor for every 10,000 people. Mali has three ventilators per million people. Average health spending in low-income countries is only $41 per person a year, 70 times less than high-income countries.

The pressure the pandemic will place on health facilities will not only affect people with COVID-19 – anyone needing any care will be impacted. This has previously been the case. During the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone there was a 34% increase in maternal mortality and a 24% increase in the stillbirth rate, as fewer women were able to access both pre- and post-natal care.

The International Labour Organization predicts 5 million-25 million jobs will be eradicated, and $860 billion-$3.4 trillion will be lost in labour income. Mass impoverishment will make treatment inaccessible for even more people. Already every year 1 billion people are blocked from healthcare by user fees. This exclusion from vital care won’t only hurt those directly affected – it will put everyone at risk, as a virus can’t be contained if people can’t afford testing or treatment.

Lockdowns without compensation are, at their crudest, forcing millions to choose between danger and hunger. As in many developing country cities, over three quarters of workers are in the informal sector, earning on a daily basis, many who stay in will not have enough to eat and so large numbers will ignore lockdown rules and risk catching the coronavirus.

As we have seen in the AIDS response, governments struggling to contain the crisis may seek scapegoats – migrants, minorities, the socially excluded – making it even harder to reach, test and treat to contain the virus. Donor countries may turn inwards, feeling they can’t afford to help others and, as the presence of COVID-19 anywhere is a threat to people everywhere, this will not only hurt developing countries, it will also exacerbate the challenge in donor countries too.

And yet, amid the pain and fear, the crisis also generates an opportunity for bold, principled, collaborative leadership to change the course of the pandemic and of society.

Seizing the public-health opportunity

Contrary to conventional wisdom that responding to a crisis takes away the capability needed for major health reforms, the biggest steps forward in health have usually happened in response to a major crisis – think of the post-Second World War health systems across Europe and in Japan, or how AIDS and the financial crisis led to universal healthcare in Thailand. Now, in this crisis, leaders across the world have an opportunity to build the health systems that were always needed and which now cannot be delayed any longer.

Universal healthcare

This pandemic has shown that it is in everyone’s interest that people who feel unwell should not check their pocket before they seek help. As the struggle to control an aggressive coronavirus rages on, the case to end user fees in health immediately has become overwhelming.

Free healthcare is not only vital for tackling pandemics: when the Democratic Republic of the Congo instituted free healthcare in 2018 to fight Ebola, healthcare utilization improved across the board with a more than doubling of visits for pneumonia and diarrhoea, and a 20%-50% increase in women giving birth at a clinic – gains that were lost once free healthcare was removed. Free healthcare will also prevent the tragedy of 100 million people driven into extreme poverty by the cost of healthcare every year.

Because COVID-19 has no vaccine yet, all countries will need to be able to limit and hold it. The inevitability of future pandemics makes permanent the need for strong universal health systems in every country in the world.

Publicly funded, cutting-edge medicines and healthcare must be delivered to everyone no matter where they live. To enable universal access, governments must integrate community-led services into public systems. This crisis has also highlighted how our health requires that the health workers who protect and look after us are themselves protected and looked after.

Given the interconnectedness between health and livelihoods, all countries will also need to strengthen social safety nets to enhance resilience. COVID-19 has reminded the world that we need active, accountable, responsible governments to regulate markets, reduce inequality and deliver essential public services. Government is back.

Financing our health

Many developing countries were already facing debt stress leading to cuts in public healthcare. In recognition that worldwide universal healthcare is a global public good, lender governments, international financial institutions and private financial actors need to both extend and go beyond the temporary debt suspensions that have been announced recently. The proposal by the Jubilee Debt Campaign and hundreds of other civil society organizations sets out the kind of ambition required.

Bilateral donors and international financial institutions, including the World Bank, should also offer grants – not loans – to address the social and economic impacts of the pandemic on the poor and most vulnerable groups, including informal sector workers and marginalized populations. Support to developing countries’ ongoing health system costs needs to be stepped up. It would cost approximately $159 billion to double the public health spending of the world’s 85 poorest countries, home to 3.7 billion people. This is less than 8% of the latest US fiscal stimulus alone. It is great to see donor countries using the inspiring and bold language of a new Marshall Plan – but currently pledged contributions are insufficient.

Business leadership

A new kind of leadership is needed from business too; one that recognizes its dependence on healthy societies and on a proper balance between market and state. As President Macron has noted, this pandemic “reveals that some goods and services must be placed outside the rules of the market”. ’The past decade has seen a rapid increase in the commercialization and financialization of healthcare systems across the globe. This must end.

As a group of 175 multimillionaires noted in a public letter released at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2020 in Davos, it is time for “members of the most privileged class of human beings ever to walk the earth” to back “higher and fairer taxes on millionaires and billionaires and prevent individual and corporate tax avoidance and evasion.” Responsible business leaders should support corporate tax reform, nationally and globally, that will necessarily include higher rates, removing exemptions, and closing down tax havens and other tax loopholes.

Despite the lessons from AIDS, monetizing of intellectual property has brought a system of huge private monopolies, insufficient research into key diseases and prices that a majority of the world can’t afford. Countries will need to use all available flexibility to ensure availability of essential health treatments for all their people, and secure new rules that prioritize collective health over private profit. There needs to be prior international agreement that any vaccines and treatments discovered for COVID-19 will be made available to all countries. The proposal by Costa Rica for a “global patent pool” would allow all technologies designed for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of COVID-19 to be openly available, making it impossible for any one company or country to monopolize them. Developing countries must not be priced out or left standing at the back of the pharma queue.

Leadership is needed in reshaping global cooperation: the COVID-19 crisis has exposed our multilateral system as unequal, outdated and unable to respond to today’s challenges. We will face even greater threats than this pandemic, which only an inclusive and just multilateralism will enable us to overcome.

All of us need all of us

The COVID-19 pandemic is simultaneously a crisis worsening existing inequalities and an opportunity that makes those inequalities visible.

The HIV response proves that only a rights-based approach rooted in valuing everybody equally can enable societies to overcome the existential threat of pandemics. Universal healthcare is not a gift from the haves to the have-nots but a right for all and a shared investment in our common safety and wellbeing.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Related

Update

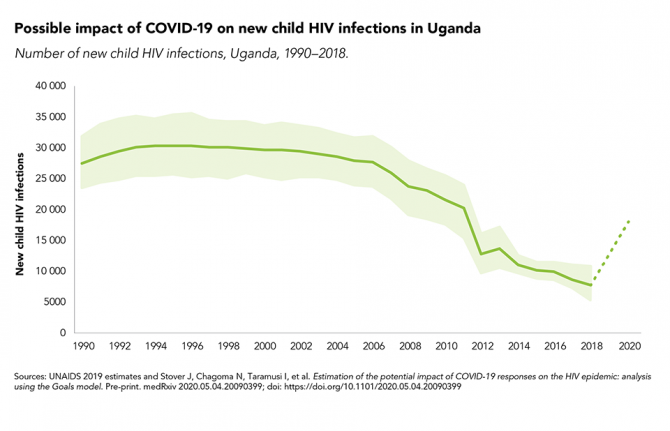

The high possible cost of COVID-19 on new HIV infections among children

19 May 2020

19 May 2020 19 May 2020New modelling has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic could have a major impact on new HIV infections among children in sub-Saharan Africa.

Since 2010, new HIV infections among children in sub-Saharan Africa have declined by 43%, from 250 000 in 2010 to 140 000 in 2018, owing to the high coverage of HIV services for mothers and their children in the region. However, if those services were disrupted because of the COVID-19 response, those gains would be reversed, with a six-month curtailment seeing new child HIV infections rising drastically, by as much as 83% in Mozambique, 106% in Zimbabwe, 139% in Uganda and 162% in Malawi.

There were approximately 30 000 new HIV infections among children (aged 0–14 years) per year in Uganda in the 1990s and early 2000s. The provision of antiretroviral medicines to prevent mother-to-child transmission scaled up from just 9% of expectant mothers living with HIV in 2004 to more than 95% by 2014, and that high coverage has been maintained since. New HIV infections among children (aged 0–14 years) plummeted to an estimated 11 000 in 2014; they further declined to 7500 in 2018. But the impact caused by COVID-19 could be high.